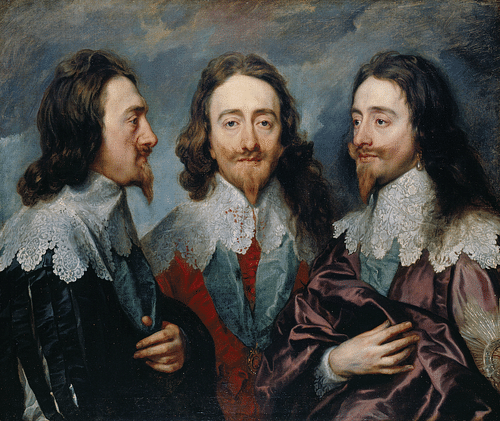

The Petition of Right was a list of demands of King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) issued by Parliament in June 1628. The petition came after three years of disagreements between the king and Parliament over finances, religious matters, and Charles' endorsement of certain key but unpopular political figures, notably the Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628).

The Petition of Right was intended to define and curb the monarch's powers and included matters of taxation, the application of martial law, imprisonment without trial, and the billeting of troops on civilian households. Charles agreed to the petition but then ignored it. Further, the king did not call any parliaments at all between 1629 and 1640, which was one of several causes of the English Civil Wars (1642-1651).

King v. Parliament

Charles, the second of the Stuart kings after James I of England (r. 1603-1625), saw himself very much as a monarch with a divine right to rule, that is he believed he was appointed by God and no mortal was above him or should question his reign. This view rather went against the growing tradition in England that Parliament should have a significant share in government, especially regarding finances. Consequently, Charles' relationship with Parliament steadily worsened as the 1620s progressed.

The convention had been established during the Tudors that a monarch called a parliament when it wanted to raise finances, for example, to fund a war or large building project. The MPs would then decide on a budget and how to raise the money, usually through various taxes and duties. Charles considered this a bothersome apparatus, which, if MPs were not compliant, might be abandoned if he could find revenue by alternative means. As the English king once stated: "Parliaments are altogether in my power…As I find the fruits of them good or evil, they are to continue or not to be" (McDowall, 88).

One of the earliest sources of discord was over customs duties, specifically the Tunnage and Poundage, a tax on the trade of wool and wine. Traditionally, a monarch was granted this revenue in their first Parliament, and it was granted for the entire duration of their reign. In Charles' case, Parliament decided to only grant this revenue for one year, after which time it would renew, a clever ploy to make sure the king recalled Parliament. Charles took this as a great insult, but Parliament was extremely wary of granting funds to a monarch who had already shown in the last years of his father's reign, when he had been, in effect, regent for the ailing king, that he was very likely to squander it on foreign wars.

The king, over the next decade, found a good number of alternative ways to raise cash, but even if they were a success in raising money, they were not particularly popular with his subjects. He imposed extra-Parliamentary taxes, sold monopolies, borrowed from bankers, and extracted new customs duties where he could. The king widened the extraction and use of Ship Money (originally imposed on coastal communities only to help fund the navy). He also imposed fines based on archaic forest laws and increased fines imposed by courts.

Perhaps most significant of all, Charles, when not granted the right to extract customs duties, instead imposed forced loans on the wealthy. These 'loans' were essentially a feudal obligation to give money to the king with only a tentative promise to ever be repaid. Not a popular move in any period, the loans came at a time when trade was depressed, there had been a run of poor harvests, and the Black Death had reared its ugly head once more. Justices of the Peace were charged with collecting the forced loans, and those who refused to pay often found themselves either imprisoned or obliged to serve in the army (or at least threatened with this). Refusing to pay a forced loan not only upset the sovereign and risked one's liberty but there was, too, a consequence for one's soul. Roger Manwaring (b. c. 1589), who became the king's chaplain, preached that those who refused would be damned.

Charles was responsible for other sources of friction with Parliament, issues which arose that MPs wanted to resolve before matters of finances were discussed. The 1626 Parliament wanted to impeach George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham after his failed and costly attack on the Spanish treasure fleets at Cadiz in December 1625. The king stood by his longtime advisor and dissolved the 1626 Parliament. Then a war with France necessitated the king finding more money via a round of forced loans in September 1626. This money was squandered on another failed military escapade led by Buckingham, this time in October 1627 in the defence of Huguenot La Rochelle against a French attack.

Yet another problem was the king's support of the Arminians from 1627. This was a branch of the Anglican Church that emphasised ritual, sacraments, and the clergy. It was not the style of preaching seen in other branches closer to Calvinism and more to the liking of most MPs who saw the endorsement of Arminianism as a dangerous shift back towards Catholicism and a reversal of the English Reformation. Even worse, the Arminians – most prominent amongst whom was William Laud – seemed to favour the idea of an absolute monarch because they supported the extraction of forced loans from the wealthy. It did not help in this situation that the queen, Henrietta Maria (1609-1669), was French and a Catholic. Another figure that was caught between King and Parliament was the anti-Calvinist Richard Montagu (b. 1577). Detested by many MPs, Montagu was supported by Charles, who made him the bishop of Chichester in 1628. The case was an example of the king's frequent unwillingness to compromise when it would have cost him very little to do so.

1627 saw yet another sticking point between King and Parliament, what became known as the case of the Five Knights. Five gentlemen were imprisoned for refusing to pay the king's forced loans, but they claimed they should not, under the ancient right of habeas corpus, be held indefinitely without trial. A court ruled in Charles' favour after pressure from the king, who now wanted the decision to become a legal precedent, something Parliament would not allow. Other grievances that year included the king permitting the application of martial law in some areas where royal troops were billeted and where locals were not properly compensated for commandeered resources. There was, too, another failed expedition to la Rochelle in May 1628. Matters finally came to a head in June.

The Petition

Nathaniel Fiennes, Lord Saye and Sele (b. 1582) was one prominent lord who refused to pay a forced loan. Fiennes then led a group of similarly disgruntled lords who took the Magna Carta of 1215 and its limitation on royal power as an inspirational precedent. MPs, in agreement with the House of Lords, drew up the Petition of Right in June 1628 in an attempt to better define royal power and avoid Charles deciding at whim his prerogative (his rights independent of Parliament). Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634), MP, lawyer, and former Speaker of the House of Commons, was another figure instrumental in gathering together the points for the petition, making it more moderate (and, therefore, more likely to be agreed upon), and helping it pass the scrutiny of the members of the House of Lords. The very use of the words 'petition' and 'right' was significant. The former suggested the king was being invited to collaborate in better defining the law, and the latter clearly indicated Parliament considered these demands a legal right.

With the Petition of Right, Parliament demanded:

- A reversal of the court's decision against the Five Knights

- An end to the king's attempts to raise money outside of Parliament

- An end to forced loans

- An end to imprisonment without trial

- An end to civilians being obliged to provide free lodgings for billeted soldiers

- An end to the use of martial law against civilians

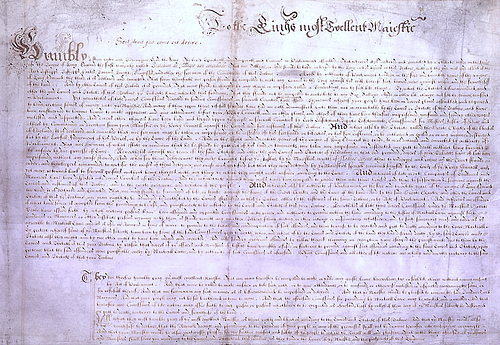

The following extract from the Petition of Right outlines these main grievances:

They do therefore humbly pray your most excellent Majesty that no man hereafter be compelled to make or yield any gift, loan, benevolence, tax or such like charge, without common consent by Act of Parliament, and that no none be confined or molested or disquieted concerning the same, or for refusal thereof and that no man be detained or imprisoned as is before mentioned; and that your Majesty will be pleased to remove the soldiers and mariners and that your people may not be so burdened in time to come; and that the commissions for proceedings of martial law may be revoked and annulled.

(Dicken, 58)

Parliament would only release funds for the king if he agreed to all the points of the petition. Desperately in need of money for his ongoing war with France, the king was obliged to agree to the demands, and the points of the petition became law. In reality, the acceptance of the petition in no way altered Charles' opinion of his status as a monarch who had no need to consult anyone on how to govern his kingdom. The king continued to extract illegal customs duties despite the protests of Parliament, his argument was they had not been specifically prohibited in the petition. This certainly soured the whole atmosphere of agreement, a situation which worsened further still when the Duke of Buckingham was assassinated in August 1628 in the Greyhound Inn in Portsmouth.

Legacy

A new parliament was convened in January 1629. Sticking points were the continued application of customs duties by the king, the jubilation of some MPs and most of the public at Buckingham's demise, and the king's support of the Arminians – he had promoted Laud to become Bishop of London, for example, in 1628. Charles promptly prorogued (suspended) Parliament. Parliament refused to be dissolved, and MPs met anyway, holding down the Speaker of the House of Commons by physical force to prolong the session. Parliament decided on the Three Resolutions: to curb the growth of Arminianism, stop the illegal collection of Tunnage and Poundage, and support those who refused to pay the king's duties. Outraged, Charles then dissolved the 1629 Parliament. Henceforth, the king decided to rule without calling any further parliaments between 1629 and 1640, a period often called the 'Personal Rule' of the king. This strategy worked well enough until the king desperately needed funds in 1639 to pay for his campaigns against a Scottish army, which had occupied the north of England, and a serious rebellion in Ireland, both fuelled by religious differences and the king's high-handed policies. Thus began the disintegration of the relationship between King and Parliament, which eventually led to the Civil War starting in 1642.

Despite the events that led to the 'Personal Rule', the Petition of Right inspired MPs in the 1640s, many of whom were protégés of Sir Edward Coke, to legislate on even bolder definitions of royal power and prerogative. In this sense, the Petition of Right is regarded as an important step in the long process of shifting from an absolute monarchy to a parliamentary democracy where the monarchy is only a part of the process of government alongside the House of Commons and the House of Lords.