The Grand Remonstrance of 1641 was a list of grievances issued by Parliament against King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649). It recorded what Parliament saw as the monarch's abuse of power, his illegal raising of taxes outside Parliament, promotion of certain unwelcome religious reforms, and use of unwise counsellors. Charles' rejection of the Remonstrance ultimately led to civil war.

The Personal Rule

The king's troubles with Parliament went back as far as the very first year of his reign. Following squabbles with Parliament over the raising of finances to fund his war with France and the humiliating curb on royal prerogative known as the Petition of Right of 1628, Charles dissolved the 1629 parliament and did not call another until 1639. The interim period is often called the 'Personal Rule' when the king was relatively successful in raising his own finances and governing his kingdom alone. Then events dictated that the king recall Parliament to raise urgent funds for an army to meet yet another Scottish invasion of northern England in 1640. This came after the king's interference in the Scottish Presbyterian Church, particularly his decision to impose a new Common Prayer Book.

The Short Parliament met in April 1640 for only three weeks and achieved nothing except upsetting the king when John Pym made a speech on 17 April calling for more powers for Parliament and the protection of MPs' privilege of independence, a defence of the Anglican Church, and an end to illegal taxation (taxes raised without the authority of Parliament). This looked very much like the Petition of Right campaign all over again. Only when these grievances were dealt with would MPs consider debating matters of finance. On 5 May, the king dissolved the Short Parliament, but the three hotspots of Parliamentary power, religion, and taxes would burn brightly through the heated political debates that raged for the next two years.

The king's need for finances had not gone away, and he called another parliament the next November, this time known as the Long Parliament. MPs, knowing the king had nowhere else to go for more cash, could now force Charles into political reforms and concessions.

King v. Parliament

The king and Parliament simply did not agree on several key issues. One of the primary demands of MPs was for Charles to replace some of his councillors. Many MPs felt that the king was a reasonable man but he was being mishandled by his advisors, who pushed him into making unnecessarily extreme decisions of policy. Charles, on the other hand, saw the Scottish invasion as a crisis of such significance that he considered it Parliament's patriotic duty to put aside their other demands and grant the king the funds to defend the order of his realm.

Another major difference between monarch and Parliament was in the area of religious reforms. Charles had begun to promote Arminianism in the Anglican Church from as early as 1627. This branch of Protestantism emphasised ritual, sacraments, and the clergy, and so was not the style of preaching seen in other branches closer to Calvinism. Indeed, some MPs were concerned that Charles intended to undo the English Reformation and return to Catholicism. This was an exaggeration since the king was himself a High Anglican, that is, he had certain sympathies with such aspects of the Christian Church as ceremony, the elevation of the clergy and bishops, and what he perceived as the beauty and order provided by certain decorations within the church building itself. For many, though, it was difficult to distinguish this from 'Popish' practices and Roman Catholic doctrine. There were, too, more concrete concerns over the Arminians' seeming support of an absolute monarchy and his right to collect taxes and customs duties as he wished, the traditional domain of Parliament.

Charles was either blissfully unaware of the concerns over Arminianism or he simply ignored them in a rather tone-deaf approach to governing the Church of which he was the head. For example, in 1633, the king appointed William Laud (1573-1645), an Arminian, as the Archbishop of Canterbury. Laud was detested by the Puritans who dominated Parliament. Many MPs wanted greater freedom for 'independent' congregations that assembled according to the individual believers' consciences and their own interpretation of the Bible. Laud outraged the Puritans when he reintroduced what were widely seen as Catholic practices into the more austere Anglican Church. These included decorating churches, railing off the altar or communion table to restrict access only for the clergy, and encouraging music. Laud banned preaching on any day other than a Sunday and replaced this with the Catechism. He also banned the weekday lectures that Puritans so valued.

The Long Parliament

The Long Parliament of 1640 continued the attitude of the Short Parliament: no discussion of finances without concessions from the king in other areas. Indeed, if anything, their position was now even stronger, and some MPs wanted to add the condition that Charles also replace his current councillors before discussions began.

Parliament would raise money to pay off the Scottish army as Charles had promised, but only if laws were passed which meant a parliament must be called at least once every three years, that it could not be dissolved by the monarch's wishes alone, royal ministers now had to be approved by Parliament, and Ship Money (a form of tax) was made illegal. Parliament, partly inspired by the radical Root and Branch Petition from several counties (which called for the abolition of bishops), also wanted to reversal of some of the Arminian reforms to the Anglican Church. To this end, William Laud was impeached.

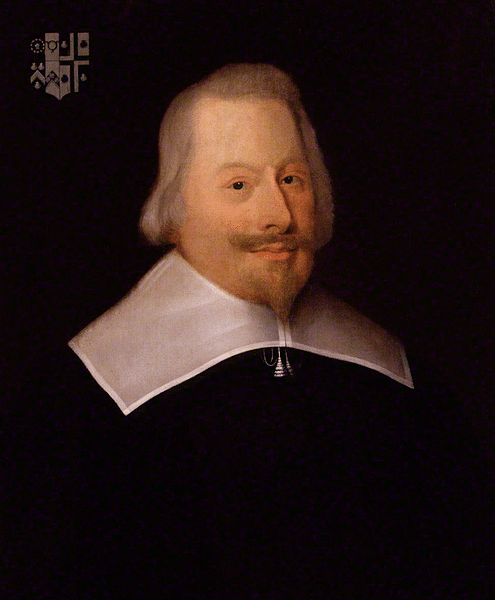

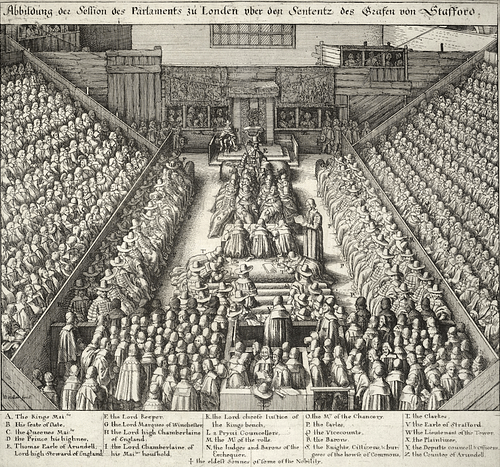

One of the decisions of Parliament which particularly struck Charles and soured relations more than ever was the trial for treason and execution of his closest advisor Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Stafford (1593-1641) on 12 May 1641. Stafford had been accused of preparing to bring an Irish army into England to aid the king, for which there was not much evidence. More significant, perhaps, was Parliament's fear of what exactly the gifted and utterly ruthless Stafford planned in the future regarding themselves.

In August 1641, the king agreed to stop raising finances outside of Parliament. Regarding Parliament's continued calls for the king to change his councillors, Charles responded with "His Majesty knows of no ill councillors" (Bennett, 16). There was then a major development with the outbreak of a significant rebellion in Ireland in October 1641. The rebels were against the policies of English land confiscation and the exclusive employment of English and Scottish immigrants on many large estates. The king wanted Parliament to find the funds to create an army to quash the rebellion, but MPs were anxious that the king use such a force in Ireland and not against themselves. This was also another opportunity for Parliament to insist the king change his councillors. MPs now packaged all of their long-standing demands into a single document: the Grand Remonstrance.

The Grand Remonstrance

The Grand Remonstrance, or Remonstrance of the State of the Kingdom as it was originally known, listed, in over 200 clauses, what Parliament saw as the king's abuses of power. Charles was accused of "a malignant and pernicious design of subverting the fundamental laws and principles of government" (quoted in Bennett, 19). The king was not the only target but also his councillors and the bishops, clergy, and Papists who wished to destabilise the country and reverse the Reformation.

The following extract is from the petition of the Grand Remonstrance:

We, your most humble and obedient subjects, do with all faithfulness and humility, beseech your Majesty, -

1. That you will be graciously pleased to concur with the humble desires of your people in a parliamentary way, for the preserving the peace and safety of the kingdom from the malicious designs of the Popish party; -

For depriving the Bishops of their votes in Parliament, and abridging their immoderate power usurped over the Clergy, and other your good subjects, which they have perniciously abused to the hazard of religion, and great prejudice and oppression to the laws of the kingdom, and just liberty of your people -

For the taking away such oppressions in religion, Church government and discipline, as have been brought in and fomented by them: -

For uniting all such your loyal subjects together as join in the same fundamental truths against the Papists, by removing some oppressive and unnecessary ceremonies by which divers weak consciences have been scrupled, and seem to be divided from the rest, and for the due execution of those good laws which have been made for securing of the liberty of your subjects.2. That your majesty will likewise be pleased to remove from your council all such as persist to favour and promote any of those pressures and corruptions wherewith your people have been grieved, and that for the future your Majesty will vouchsafe to employ such persons in your great and public affairs, and to take such to be near you in places of trust, as your Parliament may have cause to confide in; that in your princely goodness to your people you will reject and refuse all mediation and solicitation to the contrary, how powerful and near soever.

3. That you will be pleased to forbear to alienate any of the forfeited and escheated lands in Ireland which shall accrue to your Crown by reason of this rebellion, that out of them the Crown may be the better supported, and some satisfaction made to your subjects of this kingdom for the great expenses they are like to undergo in this war. (Bennett, 112-113)

The Grand Remonstrance was passed by Parliament in the early hours of 23 November 1641, but only just, with 159 votes in favour and 148 against. Some MPs believed that the king's powers were being unjustly infringed upon (especially that he could not choose his own counsellors or military leaders) and that the whole Remonstrance was too personal an attack and was too radical in its desire to address directly the people and so go above the king and the House of Lords. On the other side, the more radical members were keen to curb the king's powers even further. The crowds outside Parliament cheered its passing, even if it had no legal authority since it was not passed by the House of Lords. Many moderate MPs were pushed by these public shows of support, which involved people they considered had no right to interfere in politics, into supporting the monarchy as the only institution which would guarantee a future of ordered government. The crowds came from all walks of life, as Parliament had called for petitions whereby the commoners could air their grievances. Thousands took up the call and marched to London with their petition, creating an atmosphere of unrest. It was the beginning of a new era of politics where MPs began to receive unprecedented public scrutiny for their actions in Parliament.

The Grand Remonstrance was formally presented to the king on 1 December, but he declined to accept it, describing it as "unparliamentary" (Bennett, 20) and the exclamation "By God! You have asked that of me never asked of a king" (Dicken, 86). The rift between monarch and Parliament became even wider when the latter, in an unprecedented move, passed the Militia Bill on 7 December, which insisted that Parliament choose the commander of the army it was going to send to Ireland. The long political tussle was about to become a military one.

Aftermath

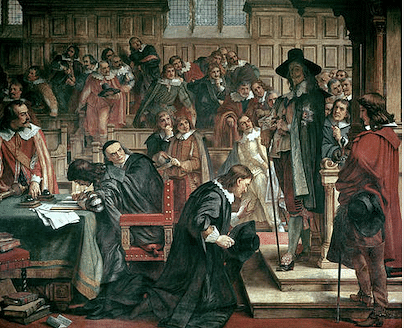

On 4 January 1642, Charles, with a few hundred soldiers, entered Parliament in person – a significant breach of protocol – and attempted to arrest the five MPs who were seen as the architects of the Grand Remonstrance. The king wished to put them on trial for treason. The five men were John Pym, John Hampden, Sir Arthur Hesilrige, Denzil Holles, and William Strode. None was in the House of Commons, having been warned beforehand of the king's plan. The king asked the Speaker of the House of Commons, William Lenthall, to assist him in determining their whereabouts but he famously replied: "[I have] neither eyes to see, nor tongue to speak, in this place, but as this House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here" (Bennett, 22).

The whole exercise was a humiliating failure for the king, who had to withdraw. Parliament, outraged at the breach of its integrity as an independent institution and fearful for the safety of its members, also withdrew, in their case to London's Guildhall. Crowds in London now heckled their king. Charles relocated to Hampton Court, and from there to York and then to Nottingham in August 1642, where a royal army was formed. Charles was now encouraged by the distinct lack of unity in Parliament as the narrow passing of the Remonstrance had demonstrated and the discord with the more moderate MPs over its public release on 15 December. For the first time, it seemed that if he did turn to a military solution to the conflicts with Parliament, he might gain sufficient support to win. Parliament also began to gather its resources and forces. So began the long and bloody series of conflicts known as the English Civil Wars, which would end with Charles execution and the abolition of the monarchy in England.