Pericles’ agora of Athens flourished under Macedonian control. After Macedon was defeated by Rome, the Romans added to the district even before Greece was taken as a province and more so afterwards. The Roman version of the agora continued as the jewel of Athens until it was destroyed by invasions in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE.

The original agora was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BCE, but the Athenian statesman Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE) oversaw its restoration and development between 460-429 BCE. This version of the district remained the commercial and political center of Athens even after Greece fell to Macedon after the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE. Under Macedonian rule, Athens was expected to keep the army of Alexander the Great (l. 356-323 BCE) well supplied but, otherwise, the city was more or less left alone.

After Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, Athens, like the rest of the Mediterranean, was caught up in the wars between his generals fighting over succession (The Wars of the Diadochi, 322 - c. 275 BCE) and the Macedonian Wars (214-148 BCE) between Macedon and Rome. During the Second Macedonian War (200-197 BCE), Athens was sacked by the troops of the Macedonian king Philip V (r. 221-179 BCE) and the agora was damaged but rebuilt. After Rome defeated Philip V of Macedon in 197 BCE and broke Macedonian power completely in 168 BCE, it played an increasingly significant role in Athenian affairs and more so after Greece was taken completely by Rome after the Battle of Corinth in 146 BCE.

The Romans treated Athens well until it joined in a rebellion and was sacked by the Roman consul and dictator Sulla (l. 138-78 BCE) c. 87 BCE. The agora was almost completely destroyed at this time. Later notable Roman citizens, however, showed their admiration for Athens by commissioning building projects which resulted in a new agora close by the old one.

This agora was destroyed by invasions by the Germanic Heruli and Visigoths in 267 CE and 396 CE respectively and was not rebuilt. Christian congregations repurposed surviving buildings or built new ones as churches and the agora continued as a commercial site and religious center. The ruins of the Roman agora, like those of the earlier period, were harvested for stone in these later building projects, but the ruins of those that were left alone, and parts of others, remain popular tourist attractions and landmarks today. The Stoa of Attalos, built as a gift to Athens by King Attalos II of Pergamon (r. 159-138 BCE) was rebuilt and restored in the 1950s CE and preservation efforts continue to maintain other structures although much of the site remains unexcavated.

Agora of Pericles

The early agora was developed under Peisistratus (d. c. 528 BCE) and his sons Hippias (r. c. 528-510 BCE) and Hipparchus (r. c. 528-514 BCE) who succeeded him. Their contributions included the Panathenaic Way, the road leading up to the temples on the Acropolis, wells, boundary stones, and various buildings all or most of which were destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BCE. Pericles ordered the agora rebuilt and used funds contributed by other city-states to the Delian League (an Athenian-led defense organization) for this purpose.

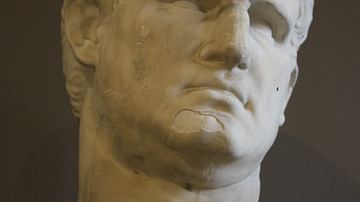

Although the other city-states objected, Pericles pointed out that Athens was still protecting them from another invasion by Persia and could do as it pleased with contributions because the money did not affect the goal of the league. The dates usually given for the restoration are from 460 BCE past the time of Pericles’ death in 429 BCE with the Temple of Hephaestus completed c. 415 BCE. This is the Classic Agora which was known by philosophers such as Socrates (l. c. 470/469-399 BCE) and Plato (l. 428/427-348-347 BCE) as well as many other famous artists, playwrights, and politicians.

Alexander & the Hellenistic Agora

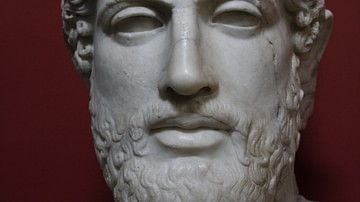

Greece was conquered by Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE) following the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE which was won largely due to the tactics of Philip’s 18-year-old son Alexander. When Philip II was assassinated in 336 BCE, Alexander succeeded him as king. The Athenians resented Macedonian rule but could do nothing about it, and Alexander more or less left them alone after diplomatic relations were established. Alexander was far more interested in his conquest of the Persian Achaemenid Empire than in Greece except as a supply line for his army.

The stability of this period encouraged a number of building projects in Athens but not in the agora. The philosopher Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE), who had been Alexander’s tutor, taught at his school, The Lyceum, there and Plato’s Academy was also active as were a number of other philosophical centers. Athens became the most famous intellectual center of its day drawing people from all points to the agora. Scholar Robin Waterfield cites the speech of the orator Isocrates regarding Athens’ reputation at this time:

Where wisdom and rhetoric are concerned, our city has left the rest of mankind so far behind that students here have become teachers everywhere else. Our city has made the name "Greek" refer no longer to a people but to a cast of thought: people are called "Greeks" not so much by virtue of their common nature, but because they share our Athenian culture. (237)

Cultural and intellectual developments characterize this era of the agora rather than construction. The works commissioned by Pericles, including the temples on the Acropolis, were all maintained as they had been since they were built. After Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, however, this changed as Athens, like the rest of the Mediterranean, was caught up in the wars of his successors. Anti-Macedonian sentiment became so common in the city that anyone associated with Alexander, like Aristotle, wisely chose to leave before they were persecuted.

Destruction by Philip V

Alexander’s general Cassander (r. 305-297 BCE) took control of Greece after Alexander’s son, Alexander IV (r. in name only 323 - c. 309 BCE) was assassinated. The monarchs who followed Cassander generally adhered to the same policy he had regarding Athens and the agora continued as it had until the reign of Philip V when his policies of expansion brought him into conflict with Rome in the Macedonian Wars.

Athens had already angered Philip V during the First Macedonian War (214-205 BCE) when they appealed to King Attalos I of Pergamon (r. 241-197 BCE), an ally of Rome, as well as others hostile to Philip V’s policies, for assistance. In 201 BCE, however, some Acarnanians, allied to Philip V, entered the sacred precinct of Eleusis while the rites of the Eleusinian Mysteries were being conducted and so defiled it. The Athenians executed them for this, and Philip V sent his army to sack Athens. The agora, and much of the rest of the city, was destroyed. The Roman historian Livy (59 BCE - 17 CE) describes the aftermath:

All the tombs and monuments in their territory had been destroyed. The shades of all their dead were exposed, bones stripped of their covering of earth. Philip had spread baleful fire throughout their ancestral shrines. (History of Rome, 31.30)

After the sack, Attalos I was again called upon by the Athenians who also appealed to Rome. Philip V was defeated by Rome at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE, died in 179 BCE, and was succeeded by his son Perseus (r. 179-168 BCE) whose policies ignited the Third Macedonian War (171-168 BCE) which ended in the Macedonian defeat at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BCE.

Sulla’s Sack of Athens

The Romans were at first seen as liberators but, although they did not take control of Greece, they increasingly involved themselves in the affairs of the city-states. There was no unified country of Greece at this time, each city-state had its own policies, laws, agendas, and concepts of government. Athens was still recognized as an important cultural center and admirers and former students, now leaders or men of means elsewhere, donated to the city’s treasury. Among these was Attalos II Philadelphus of Pergamon (r. 159-138 BCE), son of Attalos I, who gave the agora at Athens its Stoa of Attalos, one of the most impressive buildings which served as the main commercial center of the marketplace.

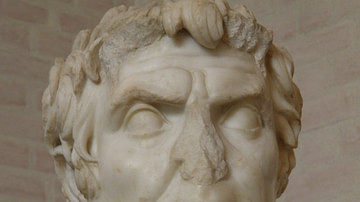

The agora continued to develop through gifts from benefactors, including Roman admirers, but the Athenians resented Roman interference as much as they had Macedonian rule. In 88 BCE, an Athenian philosopher named Aristion (d. 86 BCE), who had become friends with Mithridates VI of Pontus (r. 120-63 BCE), took control of the Athenian government as tyrant. Mithridates VI was at war with Rome at the time and Aristion encouraged Athens to support Pontus against Rome. The people followed Aristion’s lead in the hopes of expelling foreign influence and this proved to be a fatal mistake.

The Roman dictator Sulla marched on Athens, surrounded it, and lay siege. His actual goal had been the nearby port of Piraeus which supplied Athens, but he had no ships to break the Greek fleet in the harbor. The city held against him, although food ran out and the people were starving, until he was informed that one part of the walls surrounding Athens was left unguarded. Exploiting this weakness, he undermined that section of the wall and took the city. The historian Plutarch (c. 50 - c. 125 CE) describes the massacre:

There was no telling how many people were slaughtered; even now people estimate the numbers by means of how much ground was covered in blood. Leaving aside those who were killed elsewhere in the city, the blood of the dead in the agora spread throughout the part of Kerameikos that lies on the city side of the Dipylon Gate, and a lot is said to have flooded into the suburb outside the gates as well. (Life of Sulla, 14)

The Kerameikos district was on the outskirts of the agora, it was the district of the potters between the Dipylon Gate and the marketplace; which could mean that, at the least, 100 stadia (11 miles), but probably much more, was covered in blood. Waterfield comments:

Men, women, and children, weakened by starvation, were raped and slaughtered. In the first significant vandalism of the city’s antiquities, treasures were plundered and carried away to Rome by the shipload, along with nearly all the city’s slaves. Sulla later claimed that he gave orders that buildings were not to be demolished, but if this was true, it was an order his men widely ignored; many buildings in the agora suffered, and even the Erechtheion on the Acropolis was damaged by fire. (251)

Aristion was executed along with his supporters and Sulla then took Piraeus and installed a Roman oligarchy to rule Athens. In 58 BCE, Rome enlarged their province of Macedonia to include some Greek city-states, including Athens, although the city would regain some degree of autonomy later. The Athenians rebuilt as well as they could but lacked the necessary funds and even had to sell the island of Salamis for the money they needed just to survive.

Roman Agora

Eventually, they appealed to outsiders, including wealthy Romans, for donations to help rebuild but this was a slow process and many of the buildings of the agora lay in ruins for decades. When funds were made available, the donors often stipulated how the building they were paying for should look and so the agora and surrounding districts began to take on a particularly Roman architectural style. Waterfield notes:

The crumbling of old structures, along with the city’s need to make amends for having so consistently chosen the wrong side throughout the first century BCE, accelerated the process of Romanization. Not only did architectural styles change (though slowly, because of Roman antiquarianism) but individuals adopted Roman names and manners and many Romans settled in Athens as traders or exiles or passed through as students or cultural pilgrims. (253)

In 31 BCE, Octavian Caesar (the future Augustus, r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra (who had claimed Greece) at the Battle of Actium and took the region as a Roman province. The agora was afterwards known as the Market of Caesar and Augustus, and most of the extant ruins come from the reign of Roman emperor Augustus. The marketplace was entered through two gates – a main entrance to the west (Gate of Athena) and a second entrance to the east (the Propylon). The market itself was an open-air courtyard surrounded by a number of stoas (roofed colonnades) on all four sides with shops in them. The Stoa of Attalos was toward the north next to the public library. There was a large fountain to the south side and, presumably, others which may have irrigated public gardens. The best-known structures of the Roman agora are:

The Tower of the Winds – also known as the Clock of Andronicus Cyrrhestes – was probably built in the 2nd century BCE but possibly in the 1st. This is the most famous extant ruin of the agora today and was a waterclock, sundial, and wind vane. It is probably the most frequently painted or photographed structure in the Roman agora.

The Gate of Athena Archegetis (Athena the Leader) was the western entrance to the agora. It was built of Pentelic marble and funded by donations in the name of Julius Caesar and Augustus. The ruins of the gate are a well-known landmark in modern-day Athens.

The East Propylon was the eastern entrance to the agora. Built c. 19-11 BCE of Hymettian marble, its four Ionic columns still stand today.

The Odeon of Agrippa (no longer extant) was built in 15 BCE by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (l. c. 64-12 BCE), Roman statesman, general, and son-in-law of Augustus Caesar. It was a two-story auditorium that could seat an audience of 1,000 and located in the center of the agora. It was destroyed by the Heruli in 267 CE.

The Agoranomion was a long rectangular building in the eastern area of the agora dated to c. 1st century CE and dedicated to Augustus Caesar as a divinity. The building is thought to have served as a worship site for the cult of the emperor which viewed the Roman leaders from Augustus on as divinities. The façade and columns are still extant.

The Vespasianae (Latrinae) was the public latrine located in a rectangular building also toward the east. One entered an antechamber/foyer before proceeding into a square hall where stone benches with holes in them ran around the perimeter. Beneath the latrines, a sewer pipe led waste away from the area. The latrines and foundation are still extant but the building was destroyed at some point in the 3rd or 4th centuries CE.

The Fethiye Mosque dates from the 15th century CE and is the only extant building in the agora today not built by the Romans. The mosque was constructed on the ruins of an older Christian basilica which, in turn, was most likely built with stones from an earlier building in the agora district.

Conclusion

Although the Roman agora is most closely associated with Julius Caesar and Augustus, later emperors also contributed to its development. Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE), a great admirer of Greek culture from an early age, completed additions to the marketplace, including the fountain known as the Nymphaeum, elaborately decorated with statues of nymphs, and a statue of himself erected toward the market’s center. Hadrian, actually, only began the construction of the Nymphaeum, it was completed under his successor Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161 CE). Hadrian was also honored by the Greeks with a gate erected in his honor and was named a “founder of Athens” for his donations to the city.

During the Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE) the central government destabilized, and Roman provinces broke away, or attempted to, while Germanic tribes invaded where they could. The Heruli sacked Athens in 267 CE, destroying many buildings and shrines, including the Odeon and the Stoa of Attalos, and the Visigoths did the same in 396 CE, leaving the famous marketplace in ruins. One of the structures to survive was the Temple of Hephaestus from Pericles’ era which was repurposed as a church but little else remained intact.

The old agora, which had come to be regarded by the Romans as a kind of archaeological park but was never fully restored after Sulla, gradually was covered with earth and built on while the Roman agora remained in ruins after its fall. The once large area it encompassed was gradually compressed by residences built during the Byzantine Empire (330-1453 CE) and the later Turkish occupation of Greece. In the 19th century, after Greece had won its independence from Turkey, restoration and preservation efforts went into saving the extant ruins of the agora district.

In the present day, these ruins are a major tourist attraction, along with the other historical sites of Athens, drawing visitors from around the world. The reconstructed Stoa of Attalos houses a museum of the agora which exhibits artifacts from both the Greek and Roman periods when the agora was the center of the cultural life of Athens.