Empress Wu Zetian (Empress Consort Wu, Wu Hou, Wu Mei Niang, Mei-Niang, and Wu Zhao, l. 624-705 CE, r. 690-704 CE) was the only female emperor of Imperial China. She reigned during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) and was one of the most effective and controversial monarchs in China's history.

She began her life at court as a concubine of the emperor Taizong. After his death, she married his son, Gaozong (r. 649-683 CE) and became empress consort but actually was the power behind the emperor. When Gaozong died in 683 CE, Wu took control of the government as empress dowager, placing two of her sons on the throne and removing them almost as quickly. She was the power behind the throne from Gaozong's death in 683 CE until she proclaimed herself openly in 690 CE and ruled as emperor of China until a year before her death in 705 CE, at the age of 81.

Early Life

Wu Zetian was born in Wenshi County, Shanxi Province, in 624 CE to a wealthy family. She was the daughter of Wu Shihuo, a chancellor of the Tang Dynasty. Unlike most young girls in China at this time, Wu was encouraged by her father to read and write and develop the intellectual skills which were traditionally reserved for males. Wu also learned to play music, write poetry, and speak well in public.

She was very beautiful and was selected by emperor Taizong (r. 626 - 649 CE) as one of his concubines when she was 14 years old. It was Taizong who called her 'Mei-Niang' meaning 'beautiful girl' (one of the names commonly, and wrongly, attributed to her as her birth name). Although the function of the concubine in China is almost always associated with sex, a woman in this position could have a number of non-sexual responsibilities, from daily tasks like taking care of the laundry to more specialized skills like conversation, poetry reading, and playing music.

Wu began her life at court taking care of the royal laundry but one day dared to speak to the emperor when they were alone and talked about Chinese history. Taizong was surprised that his latest concubine could read and write and became fascinated by her beauty and wit in conversation. Taizong was so impressed at her intellectual abilities, he took her out of the laundry and made her his secretary. In her new position, she was constantly involved in affairs of state at the highest level and must have performed her duties well because she became a favorite of Taizong.

She attracted the attention of many of the young men at court and one of these was the Prince Li Zhi, son of Taizong, who would become the next emperor, Gaozong. Wu began an affair with Li Zhi, who was married at the time, while still attached to Taizong as concubine. Li Zhi was deeply in love with Wu but could not do anything about it because she belonged to his father and, besides, he was already married.

When Taizong died, Wu and his other concubines had their heads shaved and were sent to Ganye Temple to begin their lives as nuns. This was a common practice after the death of the emperor. The emperor's concubines could not be passed on to be used by others but were forced to end their time at court and start a new life of chastity in a religious order. However, when Li Zhi became emperor and took the name Gaozong, one of the first things he did was send for Wu and have her brought back to court as the first of his concubines, even though he had others and also a wife.

Rise To Power

Wu was given the privileged position of first concubine even though by law she should have been left in the temple as a nun. Gaozong's wife, Lady Wang, and his former first concubine, Xiao Shufei, were jealous of each other but even more envious of the attention Gaozong paid to Wu. According to Wu's own account, they conspired against her but, according to other historians, Wu started and finished the problems she had with them.

Lady Wang had no children and Lady Xiao had a son and two daughters. In 652 CE, Wu gave birth to a son, Li Hong, and in 653 CE had another son, Li Xian. Neither of these boys was a threat to Lady Wang or Lady Xiao because Gaozong had already chosen a successor; his chancellor Liu Shi was Lady Wang's uncle, and Gaozong appointed Liu Shi's son, Li Zhong, as heir. Still, this did not mean the women were not jealous of the favor the emperor showed Wu now that she had given birth to two sons in a row.

In 654 CE, Wu had a daughter who died soon after birth. The baby was strangled in her crib and Wu claimed that Lady Wang had killed her because she was jealous. Wang was the last person seen in the room and had no alibi. Wu also accused Lady Wang and her mother of practicing witchcraft and implicated Lady Xiao; Lady Wang was found guilty of all the charges and so were the others. Gaozong divorced his wife, barred her mother from the palace, and exiled Lady Xiao. Lady Wang's uncle, the chancellor Liu Shi, was removed from his post which meant his son was cut off as Gaozong's heir. Wu was now raised to the position of first wife of Gaozong and empress of China. She was also assured that her sons would rule the country after the death of her husband.

The Death of Wu's Daughter

Lady Wu played the role of the shy, respectable emperor's wife well in public but, behind the scenes, she was the actual power. She carefully eliminated any potential enemies from the court and had Lady Wang and Lady Xiao killed after they had gone into exile. Although Wu's account claims that Lady Wang murdered her daughter, later Chinese historians all agree that Wu was the murderer and she killed her child to frame Lady Wang.

The story of Wu's murder of her daughter and the framing of Lady Wang to gain power is the most infamous and most often repeated incident of her life but actually there is no way of knowing if it happened as the historians recorded it. At the time of the murder, it was Lady Wu's word against Lady Wang's, and later historians decided to side with Lady Wang against Wu; but this does not mean they chose the right side.

Any historian who has written on Lady Wu has followed the story set down by the later Chinese historians without question, but these historians had their own agenda which did not include praising a woman who presumed to rule like a man. The historians always portray Wu as ruthless, conniving, scheming, and bloodthirsty, and she may have been all of these things, she may have even murdered her daughter to gain the throne, but any of these claims should only be accepted after considering their source.

A woman in the most powerful position in government threatened the traditional patriarchy and the court counselors, ministers, and historians claimed Wu had upset the balance of nature by assuming a power which belonged to a man.

Shortly after she took the throne there was an earthquake which was interpreted as a bad omen. The scholar N. Henry Rothschild writes, "The message was clear: A woman in a position of paramount power was an abomination, an aberration of natural and human order" (108).

Omens were extremely important to the people of ancient China and played a significant role in Tang politics. In 683 CE, when Wu began manipulating events as a man would, one Confucian scholar wrote that nature had been reversed by the 'usurping woman' and "throughout the empire in every prefecture hens changed into roosters, or half changed" (Rothschild, 108).

When a mountain seemed to appear following the earthquake, this was also interpreted as nature itself revolting against the reign of Wu. Wu Zhao viewed the situation differently: she claimed the mountain was a good omen which reflected the Buddhist mountain of paradise, Sumeru. She had the mountain named Mount Felicity and claimed it had risen to honor her and her reign. Even though many at court congratulated her on being favored by the gods, many others did not. Rothschild describes a confrontation which reflects the feelings of majority of those at court. After Mount Felicity appeared, and Wu claimed it as an omen favoring her, one of her ministers wrote:

Your Majesty, a female ruler improperly has occupied a male position, which has inverted and altered the hard and soft, therefore the earth's emanations are obstructed and separated. This mountain, so born of the sudden convulsion of earth, represents a calamity. Your Majesty may take this as 'Mount Felicity', but your subject feels there is nothing to celebrate. To respond properly to Heaven's censure, it is suitable that you lead the quiet life of a widow and cultivate virtue, otherwise I fear further disasters will befall us. (108)

Wu Zhao listened to her minister and considered his argument and then, Rothschild writes, "Wu Zhao, with no intention whatsoever of 'leading the quiet life of a widow', rejected this interpretation and promptly exiled the man to the swampy, disease-ridden, Southland" (109). This particular minister was silenced but that did not silence the rest; they just were more careful not to speak their mind in front of her. Their antagonism toward a female ruler eventually would find its way into the histories which recorded her reign and become the 'facts' which future generations would accept as truth.

These historians claim that Wu ordered Lady Wang and Lady Xiao murdered in a terrible way: she had their hands and feet cut off and they were then thrown into a vat of wine to drown. This is very similar to the story of the Empress Lu Zhi (l. 241-180 BCE) of the Han Dynasty who got rid of her rival Qizi in the same way (although Qizi was drowned in a pigsty and had her eyes gouged out as well). Lu Zhi was an instantly recognizable villain to the people of China, and linking Wu with her through the murders worked to destroy Wu's reputation. Wu could have murdered her daughter but her position as a female in a male role brought her many enemies who would have been happy to pass on a rumor as truth to discredit her.

Wu Takes the Throne

Beginning in 660 CE, Wu was effectively the emperor of China. She did not hold that title but she was the power behind the office and took care of imperial business even when pregnant in 665 CE with her daughter Taiping. One example of her clout was in 666 CE when she led a group of women to Mount Tai (an ancient ceremonial center), where they conducted rituals which traditionally were performed only by men.

Having been raised by her father to believe she was the equal of men, Wu saw no reason why women could not carry out the same practices and hold the same positions men could. She did not ask any man's permission to lead these women to Mount Tai; she felt she knew what was best and did it. She also organized military campaigns against Korea in 668 CE which were so effective that they reduced Korea to the status of a vassal state.

Emperor Gaozong had nothing to do with either of these events, although his name would have been attached to the campaigns against Korea. Gaozong had caught a disease which affected his eyes (possibly a stroke) and needed to have reports read to him. Wu either read him whatever she felt like and then made her own decisions or read him the real reports and then still acted on her own. In 674 CE, Gaozong took the title Tian Huang (Emperor of Heaven) and Wu changed her own to Tian Hou (Empress of Heaven). They ruled as divine monarchs until Gaozong's death in 683 CE.

Wu placed her first son on the throne who took the royal title Zhongzong. He refused to cooperate well with his mother and his wife, Lady Wei, assumed too much power. Wei had her father appointed Chief Minister to her husband and tried to push through other measures favoring her family. When Wu could no longer tolerate her daughter-in-law's antics and disrespect, and her son's refusal to discipline her and obey Wu's dictates, she had him charged with treason and banished along with his wife.

She replaced Zhongzong with her second son, who became Emperor Ruizong. She kept Ruizong under a kind of house arrest confining him to the Inner Palace. Ruizong was also a disappointment to her and so she forced him to abdicate in 690 CE and proclaimed herself Emperor Zeitan, ruler of China, the first and only woman to sit on the Dragon Throne and reign in her own name and by her own authority. Her last name, "Wu" is associated with the words for 'weapon' and 'military force' and she chose the name 'Zeitan' which means 'Ruler of the Heavens'. She wanted to make it clear that a new kind of ruler had taken the throne of China and a new order had arrived.

Reign & Reforms of Wu Zetian

The first thing she did was change the name of the state from Tang to Zhou (actually Tianzhou or Tiansou). It was customary, when a dynasty changed, to re-set history. Each dynasty was considered a new beginning and when Wu changed the name from Tang to Zhou she was following this tradition but went further to make it clear that she was the beginning of a completely new era by calling her reign Tianzhou ('granted by heaven'). To ensure the security of her new reign she had any members of the Tang Dynasty royal family imprisoned (including the future emperor Xuanzong) and proclaimed herself an incarnation of the Maitreya Buddha, calling herself Empress Shengsen which means 'Holy Spirit'.

She commissioned statues of the Maitreya in the Longmen Caves outside Luoyang. Wu decreed that the workmen sculpt the face of the largest of these statues to resemble her and also persuaded the monks of the sanctuary at Luoyang to forge the Big Cloud Book to substantiate her claim as Maitreya. The other statues (still seen in the Longmen Grottoes) were also made to elevate her status as a divine ruler who knew what was best for the people and was divinely appointed to apply whatever laws or policies she saw fit.

As early as 660 CE, Wu had organized a secret police force and spies in the court and throughout the country. She established a policy so that informants could be paid to travel by public transportation to report to the court. This spy system served her well in giving her early warning of any plots in the making and enabled her to take care of threats to her reign before they became actual problems.

Empress Wu used the intelligence she gathered to pressure some high-ranking officials who were not performing well to resign; others she simply banished or had executed. She reformed the structure of the government and got rid of anyone she felt was not carrying out their duties and so reduced government spending and increased efficiency. In their place, she appointed intellectuals and talented bureaucrats without regard to family status or connections.

To further separate her Zhou Dynasty from the Tang, she created new characters for the Chinese writing system which are known today as Chinese Characters of Empress Wu or Zetian Characters. These characters were supposed to replace between 10 and 30 of the older characters and were Wu's attempt to change the way her people thought and wrote. Although these characters were removed after her reign they still exist as a Chinese dialect in written form. They are regarded as important by historians because they show how far Wu went in trying to create a new world in China under her reign: she even wanted to change the words they used.

No area of Chinese life was untouched by Empress Wu and her reforms were so popular because the suggestions came from the people. Under the older regimes, a suggestion or complaint had to go through a number of different offices before it ever reached anyone who could do something about it. Wu eliminated all the bureaucracy by establishing a direct line of communication between herself and the people. Historian Kelly Carlton writes:

Wu had a petition box made, which originally contained four slots: one for men to recommend themselves as officials; one where citizens might openly and anonymously criticize court decisions; one to report the supernatural, strange omens, and secret plots, and one to file accusations and grievances. (3)

Carlton further notes, "While ostensibly for her great concern over the condition of her people, the box mainly served the purpose of obtaining information on seditious subjects (3)." Although Carlton's observation is accurate, the box also did provide Wu with a number of ideas for reform which came directly from the people, not government officials who would have profited from them, and which Wu implemented efficiently.

She improved the public education system by hiring dedicated teachers and reorganizing the bureaucracy and teaching methods. She also reformed the department of agriculture and the system of taxation by rewarding officials who produced the greatest amount of crops and taxed their people the least. She ordered farming manuals to be written and distributed. She organized teams to survey the land and build irrigation ditches to help grow crops and redistributed the land so that everyone had an equal share to farm. Agricultural production under Wu's reign increased to an all-time high.

Wu also reformed the military by mandating military exams for commanders to show competency, which were patterned on her imperial exams given to civil service workers. The military exams were intended to measure intelligence and decision making and candidates were personally interviewed instead of just being appointed because of family connections or their family's name.

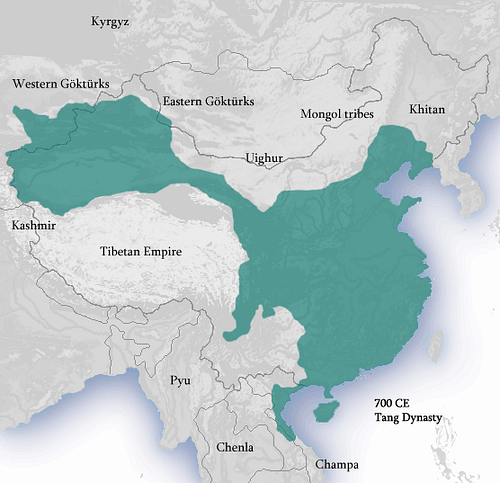

Her success in the campaigns against Korea inspired confidence in her generals and Wu's decisions on military defense or expeditions were never challenged. Her spy network and secret police stopped rebellions before they had a chance to start and the military campaigns she sent out enlarged and secured the borders of the country. She was also able to re-open the Silk Road, which had been closed because of the plague of 682 CE and later raids by nomads. Wu also took back lands which had been invaded by the Goturks under the reign of Taizong and distributed them so that they were not all held by the aristocrats.

Wu's Decline & Abdication

In 697 CE, Wu's hold on power began to slip when she became more paranoid and began spending more time with her young lovers than on ruling China. Two brothers, known as the Zhang Brothers, were her favorites and she spent most of her time in closed quarters with them. This was considered scandalous because of her advanced age and how young the Zhang brothers were but would not have even been commented on if Wu had been a man sleeping with much younger women. The practice of an emperor having young women as concubines was customary but when an empress decided to entertain herself with young men it was suddenly scandalous.

Her paranoia resulted in a purge of her administration. Anyone she suspected of disloyalty, for any reason, was banished or executed. The efficiency of her court declined as she spent more and more time with the Zhang brothers and became addicted to different kinds of aphrodisiacs. In 704 CE, court officials could no longer tolerate Wu's behavior and had the Zhang brothers murdered. Wu was forced to abdicate in favor of her exiled son Zhongzong and his wife Wei. She was in very poor health anyway by this time and died a year later.

Conclusion

After Wu's death, Zhongzong reigned but only in name; real power was held by Lady Wei who used Wu Zetian as a role model to manipulate her husband and the court. At the same time, another political faction formed around Wu's other son, Ruizong, who was supported by Wu's daughter, Taiping. In 710 CE Zhongzong died after being poisoned by Wei who hid his body and concealed his death until her son Chong Mao could be made emperor. Princess Taiping put an end to her plans when she had Wei and her family murdered and put her brother Ruizong on the throne.

Two years later, in 712 CE, Ruizong abdicated after he saw a comet one night and, following the interpretation suggested by Taiping, took it as a sign his rule was over. His son Li Longji succeeded him, ruling as Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712-756 CE). Princess Taiping had shielded Li Longji from her mother when he was young and supported him in his efforts to take the throne. She, like Lady Wei, had paid careful attention to the reign of Wu Zetian and thought she would be able to manipulate Xuanzong as her mother had Gaozong.

When she saw she would not be able to control the court as her mother did, she killed herself and Xuanzong decreed that no member of Wu's family would be allowed to hold public office because of their ruthless scheming and underhanded politics. Still, Xuanzong continued many of Wu's policies, including keeping her reforms in taxation, agriculture, and education. Under Xuanzong's reign, China became the most affluent country in the world at the time.

Empress Wu was buried in a tomb in Qian County, Shanxi Province, alongside Gaozong. A huge stele was erected outside the tomb, as was customary, which later historians were supposed to inscribe with Empress Wu's great deeds but the marker remains blank. In spite of all of her reforms and the prosperity she brought to the country, Wu was remembered mainly for her crimes against friends and family members - especially the murder of her daughter - and people did not think she was worthy of an inscription.

It could also be, like it was in Egypt after Queen Hatshepsut's reign, that no one in power wanted to record the reign of a woman and hoped that Empress Wu would be forgotten. If so, their hopes were in vain; Empress Wu Zetian is remembered today as one of the greatest rulers in China's history. The Chinese TV series Women of the Tang Dynasty (2013) featured the actress Hui Yinghong as Wu Zetian and was very popular, attesting to the continued interest in China's first and only female ruler.

Although modern historians, both east and west, have revised the ancient depiction of Wu Zetian as a scheming usurper, that view of her reign still persists in much that is written about her. The woman who believed she was as capable as any man to lead the country continues to be vilified, even if writers now qualify their criticisms, but there is no arguing with the fact that, under Wu Zetian, China experienced an affluence and stability it had never known before. Her reforms and policies lay the foundation for the success of Xuanzong as emperor under whose reign China became the most prosperous country in the world.