Hatshepsut (r. 1479-1458 BCE) was the first female ruler of ancient Egypt to reign as a male with the full authority of pharaoh. Her name means "Foremost of Noble Women" or "She is First Among Noble Women". She began her reign as regent to her stepson Thutmose III (r. 1458-1425 BCE) who would succeed her.

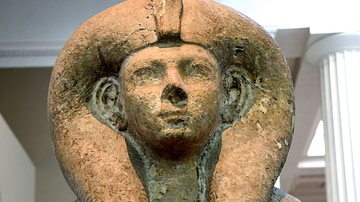

Initially, she ruled as a woman as depicted in statuary but, at around the seventh year of her reign, she chose to be depicted as a male pharaoh in statuary and reliefs though still referring to herself as female in her inscriptions. She was the fifth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty during the period known as the New Kingdom (c. 1570 to c. 1069 BCE) and regarded as one of the most prosperous and the era of the Egyptian Empire.

Although she is sometimes cited as the first female ruler of Egypt, or the only one, there were women who reigned before her such as Merneith (r. c. 3000 BCE) in the Early Dynastic Period (probably as regent) and Sobeknefru (r. c. 1807-1802 BCE) in the Middle Kingdom and Twosret (r. 1191-1190 BCE) after her toward the end of the 19th Dynasty. Hatshepsut, though not the first or last, is undoubtedly the best-known female ruler of ancient Egypt after Cleopatra VII (r. c. 69-30 BCE) and one of the most successful monarchs in Egyptian history.

Further, her name was erased from her monuments following her death which strongly suggests that someone, most likely Thutmose III, wanted to remove all evidence of her from history. Later scribes never mention her and her many temples and monuments were often claimed to be the works of later pharaohs.

Her existence only came to light fairly recently in history when the orientalist Jean-Francois Champollion (l. 1790-1832 CE), most famous for deciphering the Rosetta Stone, found he could not reconcile hieroglyphics indicating a female ruler with statuary obviously depicting a male. These hieroglyphics were found in the inner chambers of Hatshepsut's temple at Deir el-Bahri; all public recognition of her had been erased.

Since the Egyptians believed that erasing one's name from history hampered one's afterlife, it is believed that whoever removed her from public knowledge did not wish her ill after death and so preserved her name in more secluded areas. It has also been suggested that her name was simply overlooked in some places out of the public eye. Hatshepsut's building projects were numerous, after all, and it is certainly possible that those responsible for blotting her name out simply missed some. Efforts to erase Hatshepsut from memory were ultimately unsuccessful, however, as she is well known today as one of the greatest pharaohs of ancient Egypt.

Early Life & Rise to Power

Hatshepsut was the daughter of Thutmose I (r. 1520-1492 BCE) by his Great Wife Ahmose. Thutmose I also fathered Thutmose II by his secondary wife Mutnofret. In keeping with Egyptian royal tradition, Thutmose II was married to Hatshepsut at some point before she was 20 years old. During this same time, Hatshepsut was elevated to the position of God's Wife of Amun, the highest honor a woman could attain in Egypt after the position of queen and, actually, bestowing far more power than most queens ever knew.

The position of God's Wife of Amun at Thebes began as an honorary title for a woman of the upper class who assisted the high priest in his duties at the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak. The title is first mentioned in the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) as an honorific bestowed on a king's wife or daughter. By the time of the New Kingdom, however, a woman holding the title of God's Wife of Amun was powerful enough to dictate policy (though not as powerful as she would become later in the Third Intermediate Period).

Amun was the most popular god at Thebes and, in time, came to be seen as the creator god and king of the gods. In her role as this god's wife, Hatshepsut would have been considered his consort and would have presided over his festivals. This would have essentially elevated her to the status of a divine being in that it would have been her role to sing and dance for the god at the beginning of festivals to arouse him for the creative act; by engaging directly with the god, she would have taken on an elevated status. The details of the exact duties of the God's Wife of Amun are unclear but it is certain that it was a very powerful office which would only become more so later in Egypt's history.

Hatshepsut and Thutmose II had a daughter, Neferu-Ra, while Thutmose II fathered a son with his lesser wife Isis. This son was Thutmose III who was named his father's successor. Thutmose II died while Thutmose III was still a child and so Hatshepsut became regent, controlling the affairs of state until he came of age. In the seventh year of her regency, though, she changed the rules and had herself crowned pharaoh of Egypt. She took on all the royal titles and names which she had inscribed using the feminine grammatical form but had herself depicted as a male pharaoh. Van de Mieroop writes:

Whereas she had been represented as a woman in earlier statues and relief sculptures, after her coronation as king she appeared with male dress and gradually became represented with male physique. Her breasts did not show and she stood in a traditional man's posture rather than a woman's. Some reliefs were even re-carved to adjust her representation to appear more like a man. (172)

Her statuary showed her in all her royal grandeur in the forefront with Thutmose III rendered on a smaller scale behind or below her to indicate his lower status. She still referred to her stepson as the king but he was so in name only. Hatshepsut clearly felt she had as much right to rule Egypt as any man and her depiction in art stressed this. Historians Bob Brier and Hoyt Hobbs comment on this:

Her male garb was not intended to fool the citizens into believing their pharaoh was male. Statues unequivocally portray a female, whose sex, in any case, would have been obvious to any Egyptian from her name, "She is First Among Noble Women". Rather than denying her femininity, she was proclaiming that she was also a pharaoh, an office that traditionally had been held by a man. (30)

Recognizing that she was in uncharted waters, Hatshepsut took steps to legitimize her reign quickly. If her position as pharaoh were to be challenged, she was not going to allow herself to simply disappear.

The Early Reign of Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut began her reign by marrying her daughter to Thutmose III and bestowing on Neferu-Ra the position of God's Wife of Amun in order to secure her position. Even if she were now forced to relinquish power to Thutmose III she would still be in a strong position as his step-mother and mother-in-law and, further, she had her daughter in one of the most prestigious and powerful positions in the land.

These precautions were not enough, however, and she legitimized her reign by presenting herself not merely as Amun's wife in ritual but as his daughter. She claimed that Amun had appeared to her mother in the form of Thutmose I and conceived her, thus making her a demi-goddess. Her inscription relates the night of her conception as her mother lay in bed:

He [Amun] in the incarnation of the Majesty of her husband, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, [Thutmose I] found her sleeping in the beauty of her palace. She awoke at the divine fragrance and turned towards his Majesty. He went to her immediately, he was aroused by her he imposed his desire upon her. He allowed her to see him in his form of a god and she rejoiced at the sight of his beauty after he had come before her. His love passed into her body. The palace was flooded with divine fragrance. (van de Mieroop, 173)

She furthered her legitimacy through reliefs on public buildings showing Thutmose I making her his co-ruler, claiming that Amun had earlier sent an oracle predicting her rise to power, and linking herself to the expulsion of the Hyksos some 80 years before. The Hyksos were a Semitic people who established themselves at Avaris in Lower Egypt and gradually assumed enough power to control the region.

They were defeated and driven from Egypt by Ahmose of Thebes (r. c. 1570-1544 BCE) which initiated the period of the New Kingdom. The later Egyptian historians regularly characterized the Hyksos (referred to as Asiatics) as hated tyrants who invaded Egypt, sacked temples, and desecrated shrines. Even though these claims were all either exaggerations or untruths, the Egyptian memory of the hated Hyksos was strong and Hatshepsut made good use of that. One of her inscriptions reads:

I have restored what was destroyed. I have raised up what had been shattered, since the Asiatics were in the Delta at Avaris, when the nomads among them were overturning what had been made. They ruled without the god Ra and did not act by divine decree right down to my Majaesty's time. (van de Mieroop, 145)

She presented herself as a direct successor to Ahmose, whose name the people still remembered as their great liberator, in order to further strengthen her position and defend against detractors who would claim a woman was unfit to rule. Her numerous inscriptions, monuments, and temples all demonstrate how unprecedented her reign was: no woman before her had ruled the country openly as pharaoh.

Pharaoh Hatshepsut

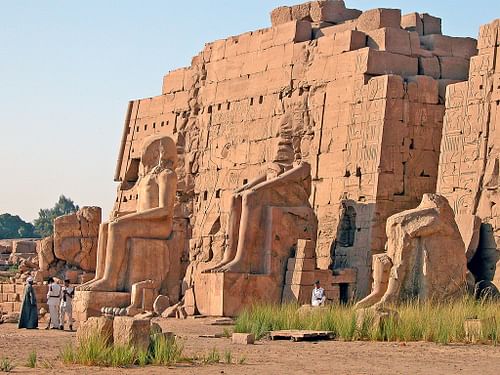

In keeping with tradition, Hatshepsut set about commissioning building projects, such as her temple at Deir el-Bahri, and sending out military expeditions. The exact nature of the military campaigns is unclear but their objectives were the regions of Syria and Nubia.

It is likely that the campaigns were launched simply to uphold the tradition of pharaoh as a warrior-king bringing wealth into the land through conquest, could have been seen as a continuation of Thutmose I's campaigns in those regions (further legitimizing her position), or could have been fairly provoked. The pharaohs of the New Kingdom, the age of empire, placed great emphasis on keeping secure buffer zones around the country to avoid a repeat of what they saw as the "invasion" of the Hyksos.

In all her projects, campaigns, and policies she relied on the advice and support of one of her courtiers, a man named Senenmut, whose relationship with the queen remains mysterious. Van de Mieroop notes that, "he was a man of undistinguished birth who rose to prominence at court. Several statues show him holding princess Neferu-Ra whose mentor and steward he became before Hatshepsut's accession" (174-175). He was in charge of all of Hatshepsut's grandest projects including her famous temple at Deir el-Bahri.

Hatshepsut's greatest efforts went into these building projects which not only elevated her name and honored the gods but employed the people. The scope and size of Hatshepsut's constructions, as well as their elegant beauty, attest to a very prosperous reign. None of her projects could have been completed as they were if she were not in command of a wealth of resources. Egyptologist Betsy M. Bryan writes:

As ruler, Hatshepsut inaugurated building projects that far out-stripped those of her predecessors. The list of sites touched by Thutmose I and II was expanded in Upper Egypt to include places that the Ahmosid rulers had favoured: Kom Ombo, Nekhen (Hierakonopolis), and Elkab in particular, but also Armant and Elephantine...However, no site received more attention from Hatshepsut than Thebes. The temple of Karnak grew once more under her supervision with the construction work being directed by a number of officials...With the country evidently at peace during most of the twenty years of her reign, Hatshepsut was able to exploit the wealth of Egypt's natural resources, as well as those of Nubia. Gold flowed in from the eastern deserts and the south: the precious stone quarries were in operation, Bebel el-Silsila began to be worked in earnest for sandstone, cedar was imported from the Levant, and ebony came from Africa (by way of Punt, perhaps). In the inscriptions of the queen and her officials, the monuments and the materials used to make them were specifically detailed at some length. Clearly Hatshepsut was pleased with the amount and variety of luxury goods that she could acquire and donate in Amun's honour; so much so that she had a scene carved at Deir el-Bahri to show the quantity of exotic goods brought from Punt. (Shaw, 229-231)

Hatshepsut's expedition to Punt (modern-day Somalia) was her crowning achievement in her own eyes. Punt had been a partner in trade since the time of the Middle Kingdom but expeditions there were expensive and time-consuming. That Hatshepsut could launch her own expedition, especially one so lavish, is a testament to how prosperous her reign was. The inscription which accompanies the relief of the expedition, engraved on the walls of her temple at Deir el-Bahri, describes the luxury goods in detail:

The loading of the ships very heavily with marvels of the country of Punt; all goodly fragant woods of God's Land, heaps of myrrh-resin, with fresh myrrh trees, with ebony and pure ivory, with green gold of Emu, with cinnamon wood, Khesyt wood, with Ihmut-incense, sonter-incense, eye cosmetic, with apes, monkeys, dogs, and with skins of the southern panther. Never was brought the like of this for any king who has been since the beginning. (Lewis, 116)

Her temple at Deir el-Bahri remains one of the most impressive and often visited in Egypt. Brier and Hobbs note how "the art produced under her authority was soft and delicate; and she constructed one of the most elegant temples in Egypt against the cliffs outside the Valley of the Kings" (30). Her temple rose from beside the River Nile with a long ramp ascending from a courtyard of trees and small pools to a terrace. Some of these trees were brought from Punt and are the first known successful transplants of trees from one nation to another in history.

The remains of these trees, fossilized tree stumps, can still be seen in the courtyard of the temple in the present day. The lower terrace was lined with columns, and a ramp led up to a second terrace which was equally impressive. The temple was decorated with statuary, reliefs, and inscriptions with her burial chamber carved out of the cliffs which form the back of the building. Hatshepsut's temple was so admired by the pharaohs who came after her that they increasingly chose to be buried nearby and this necropolis came to eventually be known as the Valley of the Kings.

Hatshepsut built on a grander scale than any pharaoh before her and, except for Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) none who came after. She had two enormous obelisks raised at Karnak in addition to those elsewhere and, as noted, commissioned building projects throughout the country. So vast were her building projects, in fact, that there are few museums featuring ancient Egyptian art and artifacts in the present day which do not have some piece commissioned by Pharaoh Hatshepsut.

Death & Disappearance

While Hatshepsut had been ruling the country, Thutmose III had not been sitting quietly by watching. She gave him command of the armies of Egypt and it has been suggested (most notably by Egyptologist James Henry Breasted) that he survived her reign by proving himself useful to her as a general and, more or less, keeping out of her way.

In c. 1457 BCE Thutmose III led his armies to put down a rebellion from Kadesh (the famous Battle of Megiddo), a campaign possibly anticipated and commissioned by Hatshepsut, and afterwards her name disappears from the historical record. Thutmose III back-dated his reign to the death of his father and Hatshepsut's accomplishments as pharaoh were ascribed to him. When and how she died was unknown until recently. Egyptologist Zahi Hawass claimed to have located her mummy in the Cairo museum's holdings in 2006 CE. An examination of that mummy shows that she died in her fifties from an abscess following a tooth extraction.

Thutmose III went on to become a great pharoah known now as "the Napoleon of Ancient Egypt" for his brilliant military victories. Later in his reign, he had all evidence of his stepmother erased from monuments and all evidence of her reign destroyed. Senenmut and Neferu-Ra had both died long before and there was no one at court, it seems, who had the power or inclination to change this policy.

The wreckage of some of these works was dumped near her temple at Deir el-Bahri and excavations brought her name to light along with the inscriptions inside the temple which Champollion was so mystified by. Although there have been many theories over the years as to why Thutmose III tried to blot Hatshepsut's name from history, the most likely reason was that her reign had been unconventional and departed from tradition.

The pharaoh's chief responsibility was the maintenance of ma'at (harmony, balance) and a woman in a man's position would have been seen as disruptive to that balance. The pharaoh served as a role model to his people and it is possible that Thutmose III feared that other women might look to Hatshepsut for inspiration and try to follow her example, thereby departing from a tradition which maintained that men should rule Egypt and women should be only consorts, as it was in the beginning of time when the god Osiris ruled with his consort Isis. Ancient Egyptian culture was very conservative in many respects and placed no value on change or alteration in tradition. A female pharaoh, no matter how successful her reign, was outside of the accepted understanding of the role of the monarchy and so all memory of that pharaoh had to be erased.

The Egyptian belief that one lives on as long as one's name is remembered, however, is exemplified in Hatshepsut. She was forgotten as the period of the New Kingdom continued and remained so for centuries. Once her name was found again by Champollion in the 19th century CE, and then by others throughout the 20th, she gradually came back to life and assumed her rightful place as one of the greatest pharaohs in Egypt's history.