The Chagatai Khanate (also Chaghatai, Jagatai, Chaghatay or Ca'adai, c. 1227-1363 CE) was that part of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE) which covered what is today mostly Uzbekistan, southern Kazakhstan, and western Tajikistan. The khanate was established by Chagatai (1183-1242 CE), the second son of Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 CE). It was perhaps the one Mongol khanate that remained true to its nomadic roots but this also meant that it developed less in economic and cultural terms than the others. The administrative capital and best-known city was Samarkand, a hub for the camel caravans which crossed Asia. Constantly at war with its neighbours, the khanate rarely achieved any stability and was overtaken by the Mongol leader Qaidu II for three decades from 1272 to 1301 CE. In the latter decades of their rule, the Chagatai khans notably promoted Islam, but dynastic squabbles led to the state's split in two and their ultimate disintegration by 1363 CE.

Foundation

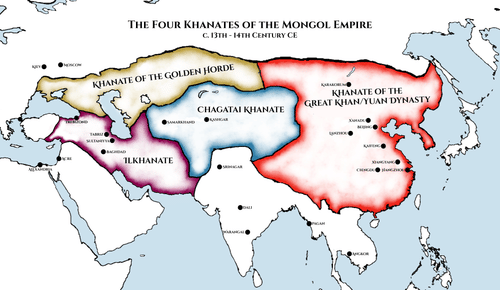

The Chagatai Khanate was founded when Genghis Khan gave each of his four sons a territory to rule autonomously within the Mongol Empire he had created from 1206 CE. Chagatai (aka Chaghadai) was the second oldest son and he was given that part of the empire in Central Asia which mostly covers today's southern Kazakhstan and parts of its neighbours. His state was thus surrounded by what would become the other three Mongol khanates: the Ilkhanate to the west, the Golden Horde to the north, and the Empire of the Great Khan (Yuan Dynasty Empire) to the east.

The Chagatai Khanate, as it would become known, was formed from the former eastern territories of the Khwarazm Empire which had been conquered by the armies of Genghis Khan in 1220 CE. Chagatai was a conservative ruler, and following his death in 1242 CE, most of his successors continued in this vein, preserving as best as possible the traditions of the nomadic Mongol tribes in their territory but, at the same time, mixing with the nomadic Turkish tribes already present in the region. In addition, Khitan tribes formed a significant minority in the state.

The Splitting of the Mongol Empire

When Mongke Khan, the 'universal ruler' or Great Khan of the Mongol Empire (r. 1251-1259 CE), died in 1259 CE, there followed a civil war between the two main candidates to succeed him, his two younger brothers Kublai (l. 1215-1294 CE) and Ariq Boke (l. 1219-1266 CE). Kublai had the support of Hulegu, who then ruled the Ilkhanate while the Chagatai ruler at the time, the regent Queen Orghina (r. 1251-1260 CE), chose to support neither and remain neutral. However, the Chagatai Khanate attracted Ariq Boke who selected Alghu, a grandson of Chagatai, to take the khanate's vacant throne and so provide him with a much-needed base for men and materials in his war with Kublai. Unfortunately for Ariq Boke, Alghu (r. 1260-1266 CE) had his own ambitions and he declared the khanate fully independent. Even worse, Alghu attacked the neighbouring Golden Horde Khanate, which was an ally of Ariq Boke's, and then declared his support for Kublai.

Meanwhile, Kublai, who had by far the richer resources at his disposal became the recognised new Great Khan in 1260 CE, even if the civil war would go on for four more years. This was essentially the moment when the four khanates became fully independent states with Kublai concentrating on China where he established the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368 CE) which he would rule as Chinese emperor until 1294 CE.

Back in Central Asia, Ariq Boke, pushed out of the Mongol capital at Karakorum, mobilised against the Chagatai Khanate but was forced to withdraw for lack of supplies. Then, in a neat blending of the old and new regimes, Alghu married Orghina in 1264 CE. With the expertise of the experienced finance minister Masud Beg, the state was now well on its way to achieving some much-needed stability.

Qaidu II

Having seen off one pretender, there remained another dangerous enemy for the Chagatais to deal with, Qaidu II (1235-1301 CE), who was a grandson of Ogedei Khan (r. 1229-1241 CE). Mongke Khan, who had been of the Tolui branch of Genghis Khan's descendants, had embarked on a ruthless purge of the rival Ogedei clan, but Qaidu had then been too young to be considered a threat and so he managed to escape to Siberia. Qaidu now saw his chance to gain himself a proper khanate of his own, especially as he gained the acquiescence of the Golden Horde to attack Alghu's territory. When Alghu died in 1266 CE and Kublai was at war in the east, Qaidu took his chance. With military support from the Golden Horde and ex-supporters of Ariq Boke, Qaidu pushed both east and west over the next five years, capturing Almaliq, defeating Alghu's successor, Baraq (r. 1266-1271 CE), in battle at Khojand and establishing himself as the dominant ruler in the region, a position he would hold from 1272 to 1301 CE. Such was the threat to the entire region's stability, a peace deal was agreed upon between the Golden Horde, Chagatai Khanate, and Qaidu's realm with a division of both certain territories and revenues from the caravan trade passing through the region. This agreement is sometimes called the Talas Covenant.

The new arrangements with their northern and eastern neighbours allowed the Chagatai to try and expand to the south at the expense of the Ilkhanate. In 1270 CE Baraq attacked but was then defeated by Abaqa, ruler of the Ilkhanate (r. 1265-1282 CE). It turned out that Qaidu had supported Abaqa and, following Baraq's death the next year, Qaidu had himself declared the ruler of the Chagatai state, although he did not take the title khan, preferring instead to nominate his own chosen candidates for that position. Nevertheless, there were still rumblings of rebellion from the descendants of Baraq and, in 1273 CE, Abaqa even sacked Bukhara.

The precarious control of his own state did not deter Qaidu from trying to expand in the east at the expense of Kublai Khan's territory, an ambition he was supported in by many traditional Mongol leaders who viewed Kublai as too susceptible to Chinese ways and so, having deserted his Mongol roots, he similarly forfeited Mongol support in central Asia. The border between the two states would constantly fluctuate as battles were won and lost, cities captured and abandoned. Only after Qaidu's death in 1301 CE did the conflict end and, by 1304 CE, there was finally a relative peace across Asia, a period known as the Pax Mongolica. From 1309 CE, the Ogedei line did not gain any position of power and the Chagatais retook control of their state.

Kebek & Tarmashirin

Border conflicts continued on all sides despite the general 'peace', but the reign of Kebek (r. 1318-1327 CE) at least brought some economic prosperity again, largely thanks to his promotion of currency use. The small silver coins now used widely across the khanate were known as kebeks after the khan himself and their name would survive in Russia, as their term kopeika became kopeks. Kebek also centralised the state and formed a new and more secure capital at Qarshi (in southern Uzbekistan).

The next significant ruler was Tarmashirin (r. 1331-1334 CE) who converted to Islam and promoted that religion in his realm. This conversion did not, however, put off the khan from launching raids into the Muslim Sultanate of Delhi. There were, too, problems now at home as traditional Mongols, most of whom practised shamanism, Tibetan Buddhism (Lamaisim) or Nestorian Christianity, saw the move towards Islam as a betrayal of their Mongol roots. This ill-feeling culminated in a rebellion which overthrew Tarmashirin in 1334 CE, although, as it turned out, most of the subsequent khans would also be Muslims and the western part of the state, in particular, became dominated by that religion.

Samarkand

The Chagatai Khanate's principal economic wealth came from the sedentary region around Bukhara and the passing through of camel caravans along the Silk Road routes. Another famous city, one of the great romantic names of Asia, was Samarkand (Samarqand), which acted as the Mongol's administrative centre following its capture in 1220 CE and after the destruction of Bukhara had made that city uninhabitable in 1219 CE. A large stretch of the mud-brick fortification walls have been excavated at Samarkand and sections of a similar wall still stand today on the citadel of Bukhara. Both cities, having been rebuilt to some degree, were ravaged a second time, almost incredibly, by the Chagatai Khanate's own ruler, Baraq. This is as good an indicator as any that the Chagatais were still very much nomads, suspicious of cities, and eager to plunder them for easy but only short-term gains, especially in times of war. The official capital of the khanate was Almaliq, located in the northeast of the state, but this was really only a geographical point for merchants to access the imperial court.

The Venetian explorer Marco Polo (1254-1324 CE) travelled across Asia and served at Kublai Khan's court between c. 1275 and 1292 CE. On his return to Europe, Marco wrote of his experiences in his book The Travels of Marco Polo or Travels (Description of the World), first circulated c. 1298 CE. In Book 1, chapter 31 of this extraordinary work, Marco describes Samarkand, which he calls Samarcan, as:

…a noble city, adorned with beautiful gardens, and surrounded by a plain, in which are produced all the fruits that man can desire. The inhabitants, who are partly Christians and partly Mahometans, are subject to the dominion of a nephew of the grand khan, with whom, however, he is not upon amicable terms, but on the contrary there is perpetual strife and frequent wars between them.

Decline

The khanate did indeed suffer from incessant warfare and went into further decline following the overthrow of Tarmashirin as different Mongol factions competed for control and there followed a line of short-reigning khans. As a consequence of this weakness, the state effectively split into eastern (Mawarannahr or Transoxania) and western (Moghulistan) halves with many local tribal chiefs then ignoring the governments of both. In addition, local Turkic emirs took control of the southern part of the state. Further disruption was caused by the arrival of the Black Death in the region during the 1340s CE. By the mid-14th century CE, the Mongol elite had by now largely become part of the sedentary societies they had once sought to conquer and the last khan, Tughlugh Timur (r. 1347-1363 CE), could not prevent the disintegration of the khanate as a definable political entity. From the 1370s CE, the former territories of the Chagatai Khanate were taken over by Timur (aka Tamerlane), founder of the Timurid Empire (1370-1507 CE) and the new dominant force in the region.