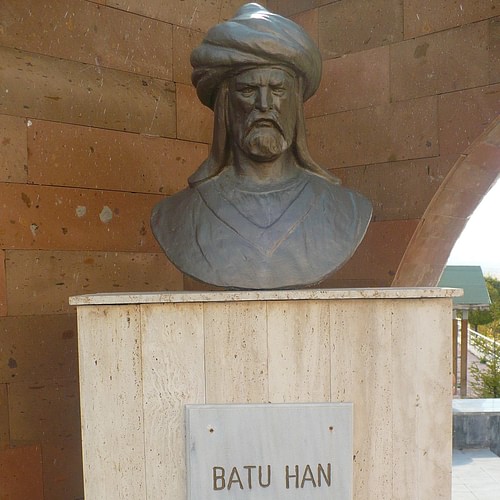

Batu Khan (l. 1205-1255 CE) was a grandson of Genghis Khan and the founder of the Golden Horde. Batu was a skilled Mongol military commander and won battles from China to Persia, although his most famous exploits involve the grand Mongol campaign into Europe from 1236-1241 CE which resulted in the Mongol horde annihilating the armies of Russia, Poland, and Hungary, among others. Later Batu would serve as the kingmaker of the Mongol Empire, effectively the most powerful man in the empire for a time.

Born in the Saddle

Batu was born around 1205 CE, right around the time that the Mongol chieftain Temujin was about to establish himself as ruler of all the Mongols and be proclaimed Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 CE). Batu was the son of Jochi, Genghis' eldest son, and so he was born into the upper echelon of Mongol society. However, Jochi was born after a rival clan had kidnapped Genghis' wife, Borte, so it was uncertain, perhaps even to Genghis, whether Jochi was really his son. Nonetheless, Batu was treated as the grandson of the Great Khan.

Batu's life would not be a relaxed one just because he was born as a Mongol elite. The Mongols were a nomadic people that ranged across the steppes, tending to flocks and moving with them by the seasons. They lived in packable yurt tents. Mongol children learned to ride practically from birth, and wrestling and archery followed shortly thereafter. These traits, which are still valued in contemporary Mongolian society, helped create the fearsome war machine that Genghis led across the known world. With this upbringing, Batu was a well-trained horseman and skilled in Mongol warfare by the time he reached adulthood.

Western Inheritance

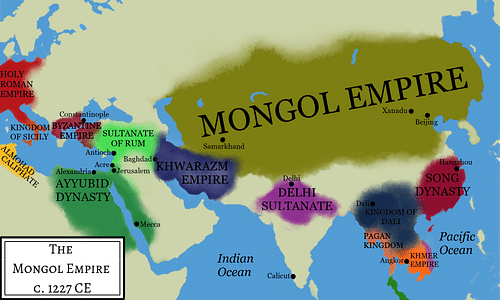

As the Mongol Empire expanded under Genghis Khan, conquering northern China and all of Central Asia, venturing into the edges of Europe and the Middle East, he laid out appanages for each of his four sons. Per Mongol tradition, the eldest son received land furthest from the homeland, so Jochi was allocated all the lands from the Ural River to, according to the Persian historian Juvaini, “as far in that direction as the hoof of the Tartar [i.e. Mongol] horse had penetrated” (42). Jochi would die the same year as Genghis, and in 1229 CE the royal family's kurultai, or council, formalized the division of appanages.

Following Jochi's death in 1227 CE, Batu and his elder brother Orda divided the Jochid appanage between themselves. Orda acquiesced that Batu should be the primary successor to Jochi, and so Orda took the territory closer to the Mongol homeland while Batu took everything to the west of the Volga. While Mongol soldiers had ventured beyond the Volga before, little of this territory had been permanently subjected to Mongol rule. Batu had the potential to rule the largest appanage in the Mongol Empire, but for now, it was just potential.

The odds of this potential ever being realized must have seemed unlikely in 1229 CE. According to custom, Genghis had left the bulk of his soldiers to his youngest son, only providing 4,000 soldiers to each of his other three sons. The kurultai had elected Genghis' third son, Ogedei (r. 1229-1241 CE), as the new Great Khan, and Ogedei Khan seemed fixated on conquering the rest of Northern China. Batu was present during these campaigns that ultimately destroyed the Jurchen Jin state in 1234 CE. In the kurultai that followed, Ogedei showed himself to be his father's son. The Mongol juggernaut would not attack just one enemy but would open up fronts across the known world. The Song Dynasty in Southern China and Korea would be targeted, and, importantly for Batu, so would Europe.

The Ride West

Ogedei gave Batu command over the European campaign. Over 100,000 soldiers were gathered to ride to Batu's appanage and make the Mongols a name Europe would never forget. Among those gathered was Subutai. Subutai was one of Genghis Khan's four orloks, or field marshals. The Secret History of the Mongols likened the four orloks to “the four dogs of Temujin,” devouring flesh and unleashing carnage wherever they went. Subutai was the true commander of this great campaign west, both due to his enviable command experience, but also because he had already campaigned successfully in Russia back in the days of Genghis Khan. During the Mongols' campaign against the Khwarazm Empire, Subutai and Jebe, another one of Genghis' “four dogs,” led a great cavalry raid from Azerbaijan up through the Caucasus and into Russia. This raid destroyed the Georgian army and plundered settlements along the Russian steppe. In 1223 CE, the Cumans and a host of Russian states combined their armies to finally put a stop to this devastating raid. At the Battle of the Kalka River, the Mongol raiding party destroyed the armies of Russia and executed Mstislav III of Kiev (r. 1212-1223). Subutai would bring this experience to the campaign, no longer a raid like in 1223 CE, but a full-fledged campaign of conquest.

Also along for the campaign were several of Batu's royal cousins. Ogedei's son Kadan, the future leader of the Ogedeid appanage, commanded a division during the campaign. The future Great Khans Guyuk (r. 1246-1248 CE) and Mongke (r. 1251-1259 CE) were also present. Like Genghis Khan's campaigns, the campaign against Europe would be an all-family affair, and it would be the last such grand campaign of the entire combined Mongol Empire.

Carving a Path of Corpses & Fire

Against this concentrated juggernaut of skilled commanders and ferocious horse archers were arranged the divided states of Europe with their peasant levies and knights laded down with heavy mail and body armor. Tales of the armies that were the scourge of god, that had easily toppled the kings of distant China and Persia, had made their way West, as well as the direct experience of the survivors from the Battle of the Kalka River. The kings and princes of Europe likely had some idea of the horror that was in store, but in reality, they could not imagine what was to come.

In 1236 CE, the Mongol horde crossed the Volga. The Volga Bulgars were defeated within the year, as were the Kipchaks and Alans. With the semi-nomadic peoples out of the way, Christian Europe lay open. Batu sent envoys demanding alliances from the princes of Russia. When they refused, their cities were besieged for just a few days before they were sacked. When Yuri II (r. 1212-1216, 1218-1238 CE) refused to bend the knee in 1238 CE, his army was destroyed, his city was burnt to the ground, and his family was slaughtered. The rest of Russia suffered a similar fate, except for Smolensky (through tribute) and Novgorod (due to distance). Later that year, Batu sacked the great city of Kiev, the center of Russian Orthodoxy, and raided through the Crimea. More Russian cities fell the next year, followed by the powerful city of Halych in 1240 CE.

While the three-year Russian campaign was impressive, it was nothing compared to what would follow. The Mongol army was still fresh, intact, and ready for more plunder. In front of them lay the true medieval kingdoms of Europe: knights in armor, crusaders from the Baltic, some of the greatest kingdoms in Europe. Yet while the militaries of states in Poland, Bohemia, Germany, and Hungary might be stronger, they were fragmented, just like the Russian leaders. If the Mongol horde had attacked each one at a time, it would be an easy victory. It turned out they did not even need their full strength to accomplish this.

Batu and Subutai had sent spies into Europe to gather information about their next operation. Subutai, ever the master tactician, split the Mongol horde into three units and outlined a three-prong attack not on one enemy, but all of Europe. However, the first two prongs were merely to draw the attention of Europe while the third and greatest prong would strike against the strongest power in Eastern Europe.

Despite being feints, the first two prongs devastated northeast and southeast Europe. Group one was led by Khadan and Baidar, sons of Ogedei. They invaded Poland and annihilated the army raised by Henry II the Pious, Duke of Silesia (r. 1238-1241 CE), and the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Legnica (Liegnitz) in 1241 CE. Their forces then laid waste to the Polish countryside while also harassing the nearby Bohemian army to keep them from trying to move south. Group two was led by Guyuk and crossed the Carpathian Mountains into Transylvania, where it defeated the local armies and proceeded to raid the countryside.

Group three, the main brunt of the campaign, was led by Batu and Subutai directly. They followed the Danube to engage with arguably the greatest enemy then in range, Hungary. Hungary had sheltered refugee Cumans fleeing the Mongols, setting themselves up as directly in conflict with the Mongols. The army of Bela IV (r. 1235-1270 CE) confronted Batu and Subutai at the Battle of Mohi (modern Muhi, also called the Battle of the Sajo River) in 1241 CE. In what was now a recurring theme, the Mongol forces slaughtered the Hungarian army.

Bela fled to Croatia, with Mongol riders hot in pursuit. The Mongols devastated Hungary, potentially killing up to 15-20% of the Hungarian population. Eastern Europe had fallen, Mongol soldiers touched the Adriatic, and the rest of Europe lay open to the Mongol hordes. Yet right then everyone was pulled back. News arrived from Mongolia: Ogedei was dead.

Kingmaker

With the Great Khan dead, Mongol law, the Yasa, demanded a kurultai of the royal family back in the homeland. All of the major princes, many of whom were campaigning in Europe, rode back home to determine who would succeed Ogedei. As the head of the Jochid branch of Genghis' family, Batu had a potential claim. The Great Khatun Toregene, the widow of Ogedei and mother of Guyuk invited Batu back, but Batu, perhaps suspecting a trap, remained in his territory, delaying the kurultai several years. Finally, in 1246 CE Guyuk was proclaimed the next Great Khan.

Meanwhile, Batu settled down to not just being a conqueror but also an administrator. Batu became the de facto ruler of the western territories of the Mongol Empire. He received the new generation of Russian princes as vassals for the Golden Horde. He appointed Mongol officials and governors for Europe, the Caucasus, and Persia. Yet Guyuk began to distrust Batu and moved west from Mongolia with an army. Sorkhokhtani Beki, the widow of Tolui, Genghis' youngest son, warned Batu that he was Guyuk's target. When Guyuk summoned Batu, Batu delayed and made excuses until Guyuk happened to die.

Sorkhokhtani Beki had made a smart bet. She had won Batu's thanks and now her son Mongke was allied with Batu. In a surprise move, Batu called a kurultai not in the Mongol heartland, as tradition demanded, but instead in his territory in Russia. This kurultai first offered the position of Great Khan to Batu, but the warlord refused. Instead, he promoted Mongke. The Jochid and Toluid branches in agreement, Batu then orchestrated a second kurultai in Mongolia itself. The other two branches of the family, the reigning Ogedeids and the Chagataids, refused to attend. Mongke was declared the fourth Great Khan in 1251 CE, and Batu enforced the decision, punishing the Ogedeids and Chagataids, executing Buri, the leading Chagataid. Mongke was Great Khan, but Batu was the kingmaker.

Establishment of the Golden Horde

Now at the height of his prestige, Batu was continuing to consolidate his hold on Russia. He defeated an uprising of Russian princes and placed the princes under an even tighter vassalage. Batu established the city of Sarai near the Volga as his administrative capital for the Golden Horde. Tribute flooded in from his vassals and laid the groundwork for future campaigns, raids, and conquests. It was from here that his descendants would continue to rule Russia from the steppe for generations to come.

When Batu died in 1255 CE, the Golden Horde passed to his son Sartuq (r. 1256 CE). The Golden Horde would continue to dominate Russia for two centuries, with Mongol kingdoms in Russia surviving until the reign of Ivan the Terrible (r. 1533-1584 CE) in the mid-16th century CE, and in the Crimea until practically the 19th century CE. Having ridden from China to Hungary during his life, Batu had left his greatest mark and legacy on the peoples of Mongolia and Russia.