The Ilkhanate (or Ilqanate, 1260-1335 CE) was that part of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE) which mostly covered what is today Iran and parts of Turkmenistan, Turkey, Iraq, Armenia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Established by the Mongol general Hulegu (d. 1265 CE), the Ilkhanate took its name from the Mongol term for viceroy, ilkhan, a title awarded to Hulegu by his older brother and then ruler of the Mongols, Mongke Khan (r. 1251-1259 CE). Throughout its history, there were regular battles to defend the khanate's territories against neighbouring states and unsuccessful diplomatic relations with the West to form an alliance against the Mamluks of Egypt, although trade agreements were established with Italian city-states. Islam was adopted by some rulers, a reflection of the dominance of that religion amongst the state's populace, even if other faiths were practised, too. The Ilkhanate came to a definitive end by the mid-14th century CE when dynastic disputes caused its final disintegration.

Foundation by Hulegu

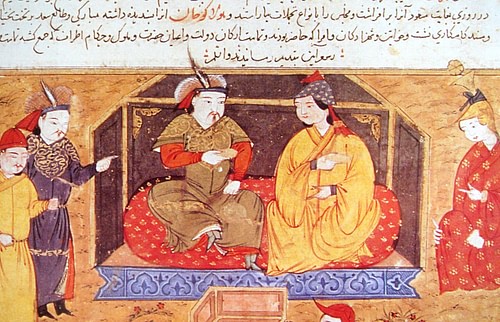

The name Ilkhanate derives from ilkhan, meaning viceroy or 'ruler of a pacified area' which was the title given to Hulegu (aka Huleu) by the then Great Khan or 'universal ruler' of the Mongol Empire, Mongke Khan (r. 1251-1259 CE). Hulegu was an able general and the son of Tolui, the grandson of Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 CE), and the younger brother of Mongke. A third brother, Kublai (the future Great Khan, r. 1260-1294 CE) was similarly made ilkhan of Mongol-controlled northern China.

Hulegu was given an army composed of two out of every ten soldiers in the empire (a scheme made possible thanks to the earlier census) and instructed to consolidate the Mongol control of western Asia, a process which had begun in the 1220s CE. From 1253 CE, Hulegu would mobilise and successfully expand his domain, centred in Iran and Iraq, crushing the troublesome Nizari Ismailis, otherwise known as the Assassins on the way in 1256 CE. More victories followed and, eventually, Hulegu defeated the Abbasid Caliphate (founded in 750 CE) of Iraq in January 1258 CE. The Mongol army captured Baghdad the following month after a brief siege. The week-long slaughter that followed - killing up to 800,000 people according to tradition - and the execution of the caliph, brought the collapse of the Abbasid Caliphate, although its empire was recentered in Cairo and became the Mamluk Sultanate (1261-1517 CE).

Hulegu then swept on until his army reached Syria and besieged Aleppo in December 1259 CE, the main city falling within a week and the usual slaughter of inhabitants following soon after. Then, in mid-1260 CE, news of Mongke's death reached them and the campaign was halted. A small Mongol army left in Syria was defeated by the Mamluks at the battle of Ain Julut on 3 September 1260 CE, but the terrain, in any case, proved unsuitable for nourishing the horses of the Mongol cavalry in the longer term.

Hulegu withdrew from the Middle East to concentrate on holding Persia; the territory he had carved out would become yet another slice of Asia under Mongol rule, the state known as the Ilkhanate. Hulegu's reign is, therefore, often dated as beginning in 1260 CE. By the end of that decade, the Mongol Empire had really become four separate and often competing khanates, each led by a different branch of Genghis Khan's descendants: the Ilkhanate, the Chagatai Khanate, the Golden Horde and the Yuan Dynasty Empire or Khanate of the Great Khan.

Rivalries with the Khanates

The Ilkhanate was involved in several battles over the next century against its three chief neighbouring states: the Chagatai Khanate to the east, the Golden Horde to the north, and Mamluk Egypt to the west. There were other, more occasional threats, too, such as the unruly Afghans and the emerging Ottomans. The Ilkhanate sometimes won and sometimes lost in this on-off but never-ending regional warfare. In 1262 CE, for example, at the Battle of Terek, the Ilkhanate was defeated by an army of the Golden Horde.

Hulegu's short reign ended with his death in 1265 CE, and he was succeeded by his eldest son (with Yesunjin Khatun), Abaqa (r. 1265-1282 CE). In 1270 CE, Abaqa defeated Baraq, ruler of the Chagatai Khanate (r. 1266-1271 CE), at the battle of Herat. More success came in 1273 CE when Abaqa sacked the city of Bukhara, then part of the Chagatai Khanate. The borders would constantly shift, but, at least now established, the Ilkhanate would ultimately stretch from eastern Turkey to western Pakistan with most of the state covering what is today Iran.

Muslim-Christian Relations

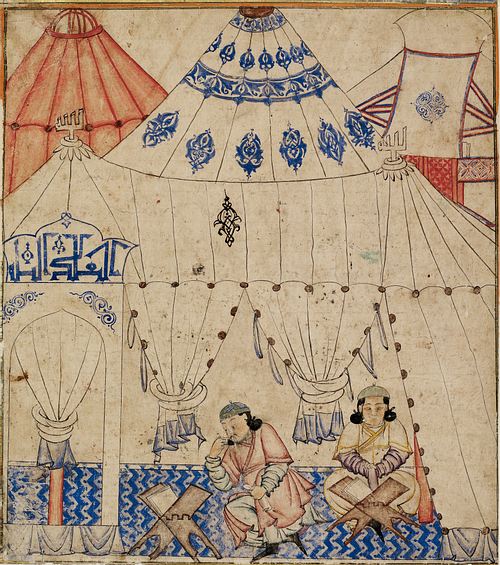

Abaqa may have favoured Nestorian Christianity in his realm, although the general populace, especially in Iran, was largely Muslim. Certainly, the ilkhan's coins carried both a cross and a Christian formula. There were also a sizeable number of Monophysite and Greek Orthodox Christians in the Ilkhanate's mixed population that included minorities of Turks, Arabs, Kurds, Armenians, and Georgians amongst others. The Mongols traditionally permitted any religion to thrive provided it was not a threat to the state or anyone else, but there was a certain tension between the hitherto dominant Muslims and the many other faiths in the state, which included a sizeable number of Jews, Zoroastrians, and Buddhists besides the abovementioned Christians.

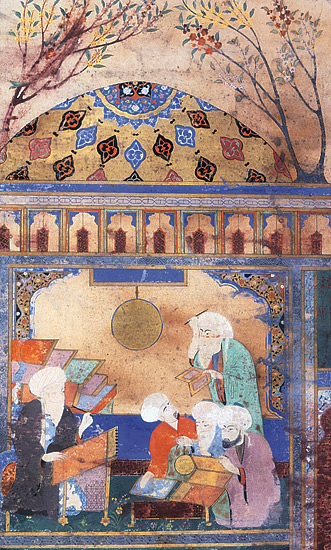

The Muslim elite - in the form of brotherhoods and the ulema - learned men of religion and law - continued to dominate the culture in general by sheer weight of numbers and better representation in the formal institutions of the state. Islamic arts and scholarship also thrived with such notable figures as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201-1274 CE) who is credited with several important astronomical discoveries from his observatory at Maragha as well as the invention of trigonometry.

As the state gained an international status, there were overtures from the Pope to try and gain the Mongols as an ally against the Muslim Mamluks in the West's seemingly never-ending crusades to conquer and keep hold of the Holy Land. Besides matters of religion, there were trade contacts with Europe, the Ilkhanate signing a trade agreement with Venice in 1271 CE, and merchants from that city were present in Tabriz, then the capital of the Ilkhanate, located just west of the Caspian Sea.

The Mamluks posed the greatest threat to the Ilkhanate, but in 1277 CE a Mamluk army was defeated in Lesser Armenia. Then, in October 1281 CE, the Mongols suffered a reverse to the same foe. In 1284 CE, Ahmad Teguder, who had reigned as ilkhan only since 1282 CE, was assassinated. Teguder had been the first ilkhan to convert to Islam, but it did not bring about any change in relations with the Mamluks as Mongol leaders continued in their belief that they had a divine right to rule the whole world whatever religion was dominant where. In any case, Teguder's successor, Arghun (1284-1291 CE), although perhaps a convert to Buddhism himself, favoured Christianity. Arghun gave tax favours to churches, sent an embassy to the Pope and to England, received Catholic missionaries into the country, and even had his son Oljeitu baptised. Once again, while nothing concrete was arranged with the western powers regarding a joint crusade, a trade deal was agreed with an Italian city-state, this time Genoa in December 1288 CE.

A Waning Economy

The stability of the state was endangered following the dynastic wrangles between the Ilkhans Baidu and Gaikhatu from 1291 CE following the death of Arghun, with each taking a turn and each being overthrown. The period saw vast overspending by the state caused by ill-advised handouts to favoured aristocrats and the disastrous introduction of paper money which nobody could quite get used to. The persistent wars with neighbours did not help either and greatly disrupted the lucrative camel caravans which crisscrossed Asia. Even agriculture was suffering, a situation first brought about by the Mongols' destruction of the ancient qanat irrigation system when they had first invaded the region from the 1220s CE. These underground canals had ensured desert areas were made suitable for farming but their repairs needed intense labour which the Mongols struggled to provide in areas where wars had led the peasantry to permanently seek safer areas to live.

A Muslim State

The next ilkhan was Ghazan (r. 1295-1304 CE), eldest son of Arghun, who took power thanks to a wave of unpopularity regarding Baidu. The new ilkhan sorted out the economy by issuing a new and centrally-controlled coinage. Significantly, considering the failure of paper money, Ghazan's coins sometimes carried the legend 'real money.' Ghazan converted to Islam in 1295 CE, however, once again this did not stop him attacking the Mamluks, capturing briefly Aleppo and Damascus in November 1299 CE, and then again attacking Syria in 1303 CE, but this time only ending in a defeat at Marj al-Suffar. Ghazan's conversion to Islam did see the Ilkhanate, for the first time, officially become a Muslim empire. Ghazan's coins now bore another legend: 'Emperor of Islam.' This shift resulted in many Christian churches, Buddhist temples, and other non-Muslim places of worship being destroyed, but some escaped the purge, especially in areas where the Muslim population was not the majority such as the north-eastern part of the state (today's Georgia and Armenia).

From 1304 CE, there then followed a period of relative peace and stability across the Mongol Empire, often called the Pax Mongolica. This allowed the new ruler, Ilkhan Oljeitu (r. 1304-1316 CE), the brother of Ghazan, to complete construction of a new capital at Sultaniyya, located just south of its predecessor Tabriz. The capital was adorned with beautiful domed mosques and fortified walls with octagonal towers, but little remains today, except the ruined tomb of the man who oversaw its growth. Oljeitu converted to Shiite Islam in 1310 CE, and the religion would be widely adopted as well as influential in terms of general culture, art, and architecture. The cultural achievements are perhaps best seen in the figure of Rashid al-Din Hamadani (1247-1318 CE), grand vizier of the Ilkhanate, who famously wrote a history of the known world, the Compendium of Chronicles, an invaluable source of Mongol history for modern scholars.

Disintegration

In 1322 CE a peace treaty was finally drawn up with the Mamluks, and the state seemed as healthy as it had ever been. However, in 1335 CE, the death of Ghazan's son and successor, Abu Said (r. 1316-1335 CE), brought another series of dynastic squabbles - not helped by the young ilkhan requiring a regent in the early part of his reign, the overly ambitious general Choban. The political instability was then made much worse by the lack of an heir when Abu Said died, perhaps from poisoning in 1335 CE. The struggle for power centred on different Muslim factions, and many of the protagonists did not even make the history books, never mind win overall domination of their rivals. This time the lack of unity was fatal to the Ilkhanate, which broke up into competing micro-khanates, making them vulnerable to the Golden Horde which was still thriving. From the 1370s CE, the former territories of the Ilkhanate were taken over by Timur (aka Tamerlane), founder of the Timurid empire (1370-1507 CE) and the new dominant force in the region.