The Mongol Empire accepted and promoted many other cultures. Historians often talk about cultural exchange across Asia in the Mongol Empire as something that was just facilitated by peace and stability across such a huge area – the 'Pax Mongolica'. However, the Mongols were active agents in this process, trying to use the many cultures of their empire(s) to expand and consolidate their rule.

The Ilkhanate & the Yuan Dynasty

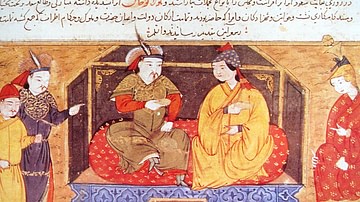

Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227) conquered much of Asia in his lifetime, and his heirs continued the job. After the death of Genghis' successor, there was a brief succession dispute, and Möngke Khan (r. 1251-1259) took over as Great Khan. Möngke was the son of Genghis' youngest son, Tolui, so Möngke's family were called the Toluids.

The previous Great Khans had already taken over what is now eastern Iran and northern China, but the Mongol Empire was not done yet. They had never established firm rule in Iran and much of the territory was effectively ruled by rival warlords. Meanwhile, there was plenty of room for expansion south into China and Tibet. Möngke and his brother Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294) had their hands full leading campaigns into East Asia, so in 1253 Möngke sent another brother, Hülegü (1217-1265), to pacify Iran. Hülegü not only destroyed one of the greatest powers in the land, a kind of Shia sect called the Ismailis, but continued on into what was left of the Abbasid Caliphate. By 1258 CE, he had captured Baghdad.

A year later, Möngke died, and civil war between the Mongols broke out. Kublai eventually won (1264) and became the Great Khan. The various Mongol rulers still saw themselves as part of the same empire, but after the civil war, the sense was much looser and the different khans took on separate identities and policies. Now we can talk of successor states. Kublai's state was the Yuan Dynasty, the Mongol rule of China, and Hülegü Khan's was the Ilkhanate, encompassing modern Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and eastern Turkey.

These two had a special relationship. Both dynasties were of Toluid lineage, and they had to show unity against the non-Toluid rulers of the other Mongol states. What's more, they both implanted themselves in rich, highly sophisticated urban societies with roots far back into antiquity. The traditionally nomadic Mongols were suddenly at the head of powerful cultures. This was a great challenge, but also an opportunity. They used multiculturalism in three ways: to help run the empire, to obtain unique services, and to display the far reach of their power.

Administration

From the earliest expansion of the empire beyond the steppe, Genghis Khan needed to effectively rule sedentary societies. Settled and nomadic lives are very different. For one thing, the level of specialisation (i. e. distinct professions) is much higher in sedentary societies. Genghis took on Uyghurs (a predominantly Muslim Turkic people) in the early days to fill such roles on behalf of their Mongol masters. This need only grew.

In the Yuan Dynasty, Chinese institutions were made to serve their new Mongol rulers. Bolad Aqa (d. 1313) was the son of the ba’urchi of Börte, Genghis' chief wife. Ba’urchi literally means cook, but this was a very high-status position in Mongol society. It needed the utmost trust from the master or mistress and gave them control of the household, as well as frequent personal access. Bolad's record on the Yuan court rolls is Po-lo, which historians have long mistaken for Marco Polo (1254-1324). In some ways, though, Bolad is like a real version of the mythologised Marco. He was a close associate of Kublai Khan, and he did have a career that took him across the Silk Road. Incidentally, Bolad and Marco may even have met, for both were at the Yuan court in the late 1270s and early 1280s.

Bolad grew up speaking Chinese and his fluency helped him collaborate closely with Chinese officials. Together they founded several Chinese-style institutions to serve the new dynasty and also revitalised some that had lost prestige with the conquest. For example, Bolad persuaded Kublai to increase the powers of the Office of the Grand Supervisors of Agriculture – originally founded all the way back to the Han Dynasty (202 BCE to 220 CE) – and reinstate its ceremonies. Then, in 1273, he began work on the Imperial Library Directorate, dedicated to preserving Chinese documents, maps, and pictures, including books of forbidden magic. Here was a Mongol, serving a Mongol Khan, using Chinese resources to rule China.

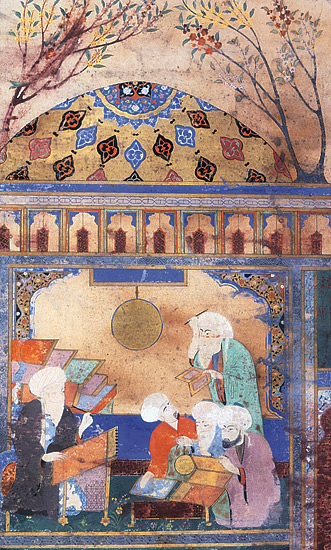

Sometimes, the Mongols faced the problem of trying to rule many, various cultures all at once, which called for truly multicultural solutions. One problem that Hülegü had was that the people of the Ilkhanate used very different dating systems. No one could know exactly when something happened or was going to happen if the Chinese, Nestorian Christians, Muslims, and Persians all used different methods of figuring out the date. (Although the Persians were predominantly Muslim, many preferred the old Zoroastrian calendar, referring to the ascension of a Sassanian king Yazdegerd III in 632 CE.) For Hülegü, the solution was astronomy. He was keenly interested in the subject and saved all the astronomical instruments from an Ismaili fortress he captured, as well as the Ismaili mathematician Nasir al-Din Tusi.

A story from the time runs that, after losing a battle to the Mamluks in 1260, Hülegü ordered every Mamluk in the realm killed. However, one man managed to save himself simply by saying he was an astronomer, at which he was immediately let go. That certainly accords with Hülegü's next move. He founded an observatory at Maragheh, near the capital Tabriz, and furnished it with books and instruments from across Eurasia. Then, he gathered a crack team of astronomers from all the different traditions, headed by Nasir al-Din Tusi and a Chinese counterpart from Yuan. They worked at Maragheh, under tight security to prevent anyone stealing their cutting-edge discoveries, until they had compiled the Zij-i Ilkhani, the 'Astronomical tables of the Ilkhans', which equates all the dating systems. In addition, this multicultural collaboration produced results that challenged the ancient orthodoxy of Ptolemy, so much so that some historians have called it a scientific revolution.

Specialist Services

The Mongols knew that the innovations of their subject peoples could give their empire a strategic advantage which no lesser empire could match. This was a virtuous circle: the more people, the more power, the more growth, the more people.

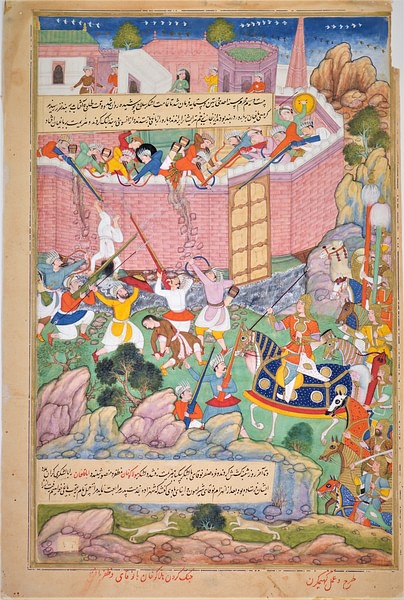

When Hülegü first arrived in Iran, he brought Chinese siege engineers with him. Sieges had always been a problem for the lightning-fast tactics of Mongol warfare, so rulers quickly got others to do it for them, especially the northern Chinese. Guo Kan (1217-1277) was one such siege engineer, present at the conquest of Baghdad in 1258. He was the distant descendent of Guo Baoyu, who had finally suppressed the An Lushan rebellion in the 9th century. According to the rather exaggerated dynastic history, Guo Kan more than matched him. He allegedly ran the Iran campaign almost entirely by himself and conquered far further west than Hülegü's armies ever went.

Guo Kan supposedly even captured the caliph of Baghdad by laying a floating bridge across the river to prevent an escape by boat. This is all embellishment, but the role of Chinese siege engineers was indeed vital. A floating bridge device did indeed capture the caliph's dawadar (chancellor), and Chinese engineers almost certainly designed it – it is even plausible that Guo Kan himself did. Some historians have argued that they brought gunpowder, but this is unlikely. What the Chinese had to offer was specialism in siege engineering and the creation of war machines.

There were other contingents aside from the Chinese. Auxiliaries and allies played a crucial role in the war machine. At the Battle of Homs against the Mamluks in 1281, the Ilkhanate brought contingents from Armenia, Georgia and the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, their tributary states. They were also assisted by the Knights Hospitaller. The knights were there because Christian Armenian notables had presented the pagan Mongols as spiritually acceptable allies to Latin Christian audiences. They stressed that the Mongols treated Christians in their realms well (which was reasonably true), that they were close to baptism (which was a stretch), and even that great Mongols had converted to Christianity in the past (which was a lie). These confidence-building exercises by subjects of the Mongols were vital to their military endeavours – even if, in the case of the Mamluks, they were not successful.

For the Mongols, spiritual and magical power was just as important as material, and just as useful in their campaigns of conquest. The Yuan Dynasty deliberately united many forms of magic. Bolad helped reinstate ritual sacrifices at the Chinese temples of Heaven, Earth, and Grain, but now the officiate would sacrifice an animal, Mongol style. Yuan divination embraced horoscopes drawn from Chinese and Islamic traditions. Heavenly events were thought to be omens, so astronomy-astrology particularly appealed to the Yuan elite. In fact, astrologers would compete to predict lunar eclipses the most accurately, and the best would get the favour of the ruler. Still, the Khans complemented all this with their own traditional Mongol forms of divination: a Tölgechin (diviner) might see the future through the cracks in burnt sheep bones, by rolling dice, or looking at the flight trajectories of birds. The English monk and scientist Roger Bacon (1219-1292) thought that these eclectic divinations gave the Mongols a better look into the future than anyone else, which explained their exceptional military success.

Another prominent form of magic was geomancy. Mongol warriors were experienced strategists and nomadic herders, traits which gave them a particular sensitivity to toponymy. They believed lands had magical properties, alongside their material ones, and these could be manipulated to gain their favour. One story goes that Kublai smoothed a map – the representation of the land – with his hand and thereby came up with a winning strategy. In other words, the land let Kublai's plan work because it had been symbolically placated. The Yuan court also made extensive use of both Chinese 'wind and water' (better known as feng shui) and Islamic 'science of sand' geomantic techniques.

Display of Power

Grand displays of multiculturalism could show the wealth, size and magnificence of the Mongol Empire. This certainly was showing off, but it was more than that, too. Mongol ideology, developed in the time of Genghis Khan, was that Heaven had appointed the Mongols to rule over the entire world. They could make their claim to universal rulership visible by gathering representations of many, diverse cultures. In addition, they may have believed this had a magical effect. Steppe societies, as well as the Chinese, had long believed that a microcosm might influence a macrocosm, so the stability of the empire might be ensured by showing the harmony of symbols of its many cultures.

Yuan cuisine was a combination of a startling variety of styles from across Asia. The recipe book called the Yin-shan Cheng-yao (Eugene Anderson's translation: "Proper and Essential Knowledge About Drinking and Feasting") puts paid to the idea that the Mongols kept their own fare while the rulers of China then retreated to the steppes without leaving a trace on the local habits. Instead, they blended Chinese and Mongol cuisine, like seasoning Mongol barbequed sheep with Chinese spices and serving it with local vegetables. Of 98 recipes in the first part of the book, 28 are Mongol-Turkic, 33 are West Asian with Chinese influences, three are Chinese, and one is Kashmiri. There are also 28 of a combined type – what today we would call fusion – that are unknown outside of this recipe book. Some of the Yin-Shan Cheng-yao’s ingredients are distinctively West Asian, like pomegranates, walnuts, and chickpeas.

The Khagan emperors of Yuan even employed a sherbetchi. The clue is in the name, for the job of this official – always a Nestorian Christian – was to make the Mongols' favourite Iranian import: sherbet. This was a high-status, high-influence kind of job, as we know from Marco Polo's meeting with Kublai's sherbetchi. The expense of such ingredients and experts, along with the deliberate fusion, suggest the Yuan Dynasty was creating its own haute cuisine to display its vast wealth and far-reaching power over many cultures and climates, as well as filling their bellies in style. It is also worth considering that the dinner table may be an excellent example of a microcosm of the Mongol Empire. Perhaps bringing together all the cuisines of the Khagan's subjects before him and blending them into new dishes helped unite and harmonise the whole empire.

While the Yuan Dynasty was making their claim to empire in their bowls, the Ilkhans were doing it in their books. Rashid al-Din (1247-1318), a physician and convert to Islam from Judaism, became a minister of the Ilkhan Ghazan (r. 1295-1304) and later for Öljeitu (r. 1304-1316). As a major government official, he worked with Bolad on a number of cultural exchanges between Mongol Iran and China, for both men seemed to share a sense of the opportunity that Mongol rule of Eurasia afforded. Rashid al-Din's greatest contribution to history, though, was his own history, the Jami al-Tavarikh (1308), or Collection of Chronicles. In his own words:

Until now, no work has been produced in any epoch which contains a general account of the history of the inhabitants of the regions of the world and different human species… Today, thanks to God and in consequence of him, the extremities of the inhabited earth are under the dominion of the house of Chinggis Qan [Genghis Khan] and philosophers, astronomers, scholars and historians from North and South China, India, Kashmir, Tibet, the Uighurs, other Turkic tribes, the Arabs and Franks, belonging to different religions and sects, are united in large numbers in the service of majestic heaven. And each one has manuscripts on the chronology, history and articles of faith of his own people and each has knowledge of some aspect of this. Wisdom, which decorates the world, demands that there should be prepared from the details of these chronicles and narratives an abridgement, but essentially complete [work] which will bear our august name. (Allsen, 83)

This structure was novel. Rather than framing the history around a single tradition, like the account of history by the prophet Muhammed, the Jami al-Tavarikh included Chinese, Jewish, Indian, European, and Islamic history without centering any one of them. Rashid al-Din's research methods were also unusual. He had a large team of assistants and made ample use of local experts to gather his narratives, like Kalamashri the Kashmiri monk and, of course, Bolad. Additionally, he somehow managed to get access to the Altan Debten (Golden Register), a compilation of fragments about the history of the Mongol conquest kept under lock and key in the Ilkhan's treasury.

This alone should show that the Jami al-Tavarikh had the support of the Ilkhans, but any project on such a vast scale could not have been made without their patronage. Ghazan and Öljeitu wanted this book because a universal history befits a universal society. The history of the Ilkhanate had to fit into the histories of all of its subjects in order to justify its rule in their eyes. They had to see their own cultures as branches of the same society ruled legitimately by the Ilkhans. What the Jami al-Tavarikh did was to show how all these histories led quite naturally up to the unity of the world under the Mongols.

Mongol rulers embraced, rather than suppressed, other cultures in order to demonstrate that they were destined to rule over them. This inevitably worked two ways, for the Mongols were fitting themselves to others just as they were fitting others to themselves. Over time, multiculturalism created a new kind of Mongol rulership in both Yuan and the Ilkhanate and new patterns of thinking that influenced the imperial ideologies of their successor empires, like the Ottomans and Safavids.