The Khitan people formed the Liao dynasty and ruled parts of Mongolia, Manchuria, and northern China from 907 to 1125 CE. Adopting elements of Chinese government and culture, the Khitan were more than a match for their rivals the Song dynasty of China and Goryeo kingdom of Korea, and they provided a model of conquest and assimilation which would be repeated much more successfully by the later Mongol empire.

Foundation

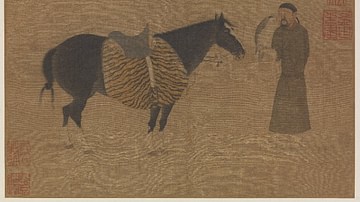

The Khitans were a semi-nomadic tribespeople under the leadership of the Yelu clan who roamed the Mongolian and Manchurian plains from the 5th century CE. Their prosperity was based on steppe pastoralism and agriculture while militarily, their excellent horsemanship made them a formidable opponent. Their first leader of note was Yelu Abaoji (872-926 CE) who formed a confederation of eight to ten tribes and gave himself the title of Emperor Taizu in 907 CE. It was Taizu who would found the Liao dynasty by casting aside the traditional method of choosing a new Khitan leader by vote and for a limited period, replacing it with a hereditary system.

Territorial Expansion

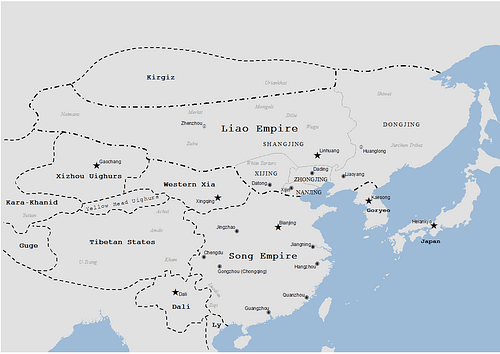

In 926 CE the Khitans conquered and assimilated the southern neighbouring Bohai people of the Balhae state (Parhae), helped by Chinese military leaders and administrators recruited for the purpose. A new kingdom, with Abaoji's son on the throne, was declared and called Dongtan. The Khitans were even more ambitious, though, under their second ruler, Emperor Taizong (r. 927-947 CE), and in 938 CE they turned south to invade parts of northern China, in disarray since the fall of the Tang Dynasty in 907 CE. Campaigning beyond the Great Wall of China, the Khitans managed to take no fewer than 16 Chinese commanderies.

China achieved some stability with the arrival of the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE), but the Chinese emperors were still struggling to manage their own population and faced another dangerous neighbour to the north-west in the form of the Xia state. So superior was the Khitan cavalry with their armoured horses, lances, bows, swords and superior horsemanship, that they continued to invade Song China at will. The Song emperors were eventually compelled to sign a peace deal, the Treaty of Shanyuan in 1004 CE, which stipulated they pay their neighbour annual tribute in the form of 100,000 taels of silver and 200,000 bolts of silk. They also recognised the Khitan ruler as an emperor in his own right and agreed not to build any border fortifications (which they did anyway). In subsequent years the weak Song state was compelled to increase the tribute payments to 200,000 taels of silver - half of China's annual production - and 300,000 bolts of silk.

Khitan expansion was not limited to the south but moved east with the Jurchen tribes of Manchuria next to be conquered by the Liao between 983 and 985 CE. The Goryeo (Koryo) dynasty of Korea (918-1392 CE) was another state that came off worse against the Khitans. Things started badly between the two states in 942 CE when the Khitans sent an embassy which included 50 camels as a gift to King Taejo of Goryeo who responded by starving the animals and exiling the envoys to an island.

Things escalated in 994 CE when Emperor Shenzong (r. 982-1031 CE) sent several expeditions deep into Korean territory. The line of six Goryeo fortresses protecting their northern border proved woefully inadequate against the mobile Khitan horsemen. The Korean rulers would also have to acknowledge Liao superiority and accept vassal status but, like the Song, trade relations were, nevertheless, maintained. Peace was not long-lasting, though, and more Liao invasions into Korea took place in 1009 CE and 1018 CE. The Koreans won a great victory at the battle of Kwiju, but the Khitan had such a position of strength they could negotiate a peace and withdraw, just as they had done in China. From 1020 CE Goryeo sent tribute to the Liao instead of Song China and adopted the Khitan calendar.

Administration

The Khitan empire was split into five administrative regions, each with its own capital. These included Shangjin (modern Harbin), capital of the northern region which was much more sparsely populated and which continued culturally and administratively unchanged. Dongjing (near modern Shenyang) was the capital of the east, and Nanjing (modern Beijing) the capital of the south, which was the richest part of the empire. The Song dynasty may have been the Khitan's military rival but they had no qualms in adopting aspects of Chinese culture and copying both the imperial administrative system and Tang Dynasty civil service examinations, especially in the southern portions of the Liao empire. Trade relations were also unaffected between the two dynasties, and much of the Song silver tribute was sent right back in payment for Chinese imports. For the Song, at least, the price for peace on its northern borders was a good one.

Thus, the Liao had a dual system of governance, one traditionally Khitan which dealt with the still semi-nomadic and pastoral north and another in the south which was much more Chinese to govern a largely Chinese population. There was also a duality in the selection of emperors. The hereditary male rulers were all from the Yelu clan but their consorts were all taken exclusively from the Xiao clan, thus ensuring both clans were represented as harmoniously as possible in the imperial household. The emperors may have acquired fantastic wealth, but according to Chinese records, they continued to regularly move from one palace to another in their various capitals, engage in hunting trips, and sometimes even slept in tents to show their people they had not forgotten their nomadic roots.

Economy & Religion

Another important difference between the Liao state and the rest of China was their support of merchants and trade. The ancient Chinese, although always great traders, did look down on the activity as beneath the merit of a gentleman. This was due to the principles of Confucianism, but the Khitan had no such qualms and the government actively supported merchants and commerce in general. They also traded with peoples across Asia, passing on sheep, horses, furs, carpets, lumber, and slaves. In return, they acquired silver, tea, silk, cotton, jade, and precious metal manufactured goods.

Buddhism was adopted as the principal religion, although traditional beliefs lived alongside it, especially shamanism and divination. The rulers sponsored the building of Buddhist temples, monasteries, and the spread of the religion through the creation of printed books. There was also a blend of Chinese and Khitan ritual in, for example, the offerings made to honour ancestors, where in China fruit and cereals were set aside, the Khitan used deer meat. Buddhism did influence Khitan art, with Chinese artists often commissioned to create it, but there was also a definite love of beautifying traditional Khitan-significant objects such as highly ornamented saddles, gold stirrups, and tent-shaped funerary urns.

Decline & Collapse

By the early 12th century CE the Liao's regional dominance was coming under increasing threat from attacks by the Jurchen, a subject tribespeople in the north-eastern part of China. The ancestors of the Manchurians, they spoke the Tungusic language and had declared their own Jurchen Jin state with Aguda, their ruler, even declaring himself an emperor in 1115 CE. There were now three separate emperors in the region and something had to give. The Song took advantage of the Jin territorial ambitions, and the two states joined forces to defeat the Liao. Aguda, now calling himself Emperor Taizu, attacked Jehol (Rehe), the Liao supreme capital, in 1120-21 CE and the Liao dynasty, weakened already by an internal schism between the sinicized elite and more traditional clans, finally collapsed four years later.

What remained of the Khitan army was reassembled and led by Yelu Dashi (1087-1143 CE), a relation of the royal family. Moving to the west in central Asia, a new Khitan dynasty was founded, the Khara Khitai (aka Xi Liao), although it would not last long and was ultimately swept away by the rise of the Mongols in the early 13th century CE.