Taejo (r. 918-943 CE), previously known as Wang Geon or Wang Kon, was the founder and first king of the Goryeo (Koryo) kingdom which unified and ruled ancient Korea from 918 CE to 1392 CE. Wang Geon was given the posthumous title of Taejo meaning 'Great Founder.' His dynasty would oversee an unprecedented flourishing of Korean culture, and its name is the origin of modern Korea's English name.

The Fall of Silla

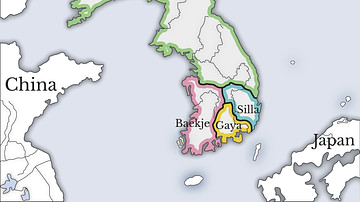

The Unified Silla Kingdom (668- 935 CE) had held sway over the Korean peninsula for three centuries, but the state was in a slow decline. Rebellions from the peasantry and the aristocracy were rife, and there followed a period of political turmoil referred to as the Later Three Kingdoms period (889-935). Gyeon Hwon, a peasant leader, took advantage of the political unrest in 892 CE and formed a revival of the old Baekje kingdom in the south-west portion of the peninsula. Meanwhile, an aristocratic Buddhist monk leader, Gung Ye declared a new Goguryeo state in the north in 901 CE, known as Later Goguryeo. Gung Ye was assisted by his first minister and general Wang Geon, the son of a wealthy merchant and local headman at Gaeseong in the Silla kingdom.

There then followed a power struggle for control of the peninsula. Gyeon Hwon attacked Gyeongju, the Silla capital, in 927 CE while Gung Ye's unpopular and fanatical tyranny led to his death at the hands of his people. He was succeeded by Wang Geon in 918 CE who probably had a hand in his predecessor's assassination. Once in power, Wang attacked Later Baekje, now beset by leadership in-fighting, and then Silla. The last Silla king, Gyeongsun, finally surrendered in 935 CE and left Wang Geon to unify the country once again but under a new name, Goryeo.

A Unified Korea

Wang Geon was eager to rekindle the former glories of the Goguryeo (Koguryo) kingdom which had thrived during the Three Kingdoms period (37 BCE – 668 CE) and so named his new kingdom Goryeo after it, which means 'High and beautiful.' Perhaps for the same reason, Wang selected the northern city of Songdo/Songdak (Modern Gaeseong) as his new capital. Wang Geon declared himself king, and for his contribution to creating the new state was given the posthumous title King Taejo or 'Great Founder.'

Wang maintained many of the Silla institutions of government and to ensure the loyalty of the conquered Silla and Baekje elite he distributed lands and prominent Goryeo government positions to Gyeongsun and other aristocrats. Concerned that he would one day be the victim of an uprising like his predecessor, Wang married into several elite families and clans, a strategy which resulted in the new king eventually acquiring six queens and 23 consorts. Wang would be the father of 25 sons and nine daughters. The king is also credited with expanding the aristocracy's access to higher government positions, building new schools and improving agricultural yields by easing the tax burden on the peasantry.

Wang continued to endorse Confucianism, Buddhism, and Shamanism as the state's main three religions. Wang was a particular follower of the latter and a believer in pungsu, the practice of carefully selecting geographical locations to benefit from the natural life forces thought to emanate from trees, rivers, and mountains. Wang was strongly influenced by pungsu in his selection of his main and regional capitals.

Buddhism was the most important and practised religion, as it had been for centuries in Korea, and this is evidenced by Wang's sponsorship of many temple building projects, including ten new Buddhist temples at the capital. Indeed, Wang credited his success in creating the Goryeo kingdom to his faith in Buddhism:

The success of the great enterprise of founding our dynasty is entirely owing to the protective powers of the many Buddhas. We must therefore build temples for both Son and Kyo Schools and appoint abbots to them, that they may perform the proper ceremonies and themselves cultivate the way. (Portal, 81)

Foreign Policy

Taejo's kingdom was far from secure, though, and the Khitan (Qidan) tribes in the north proved stubbornly resistant to Goryeo's expansionist policies of the late 10th and early 11th century CE. Refugees fled from Balhae (Parhae), the northern Manchurian state, to Goryeo at this time following its collapse in 926 CE at the hands of the Khitan. The latter were eventually subdued and contained by the construction of a great wall across the peninsula's northern frontier. Pyongyang was also given a greater importance to act as a deterrent for further incursions. The hatred never stopped, for when the Khitan sent an embassy and a gift of 50 camels in 942 CE, Wang responded by exiling the ambassadors to an island and allowed the camels to starve to death.

Wang was busy in the south, too, as there he conquered the island of Tamna (Cheju). Relations with China were peaceful; the Later Tang dynasty recognised Wang as the ruler of Korea in 932 CE, and there was continued trade and cultural exchange, especially with the rise of the Song dynasty during the reign of Wang's immediate successors, starting with his son Mu (King Hyejong) and then Mu's brother Jeongjong.

Ten Injunctions

Just prior to his death in 943 CE, Wang famously produced a list of points that he wished his successors to follow in running the state of Goryeo. Wang demanded that they "should be read morning and night and forever used as a mirror of reflection" (Seth, 99). These are known as his 'Ten Injunctions' (Sip Hunyo), and while some historians suggest they may have been written in the century after Wang's death, they, nevertheless, had a profound influence on government policy long after they were written. They are summarised in Pratt (466) as follows :

- The state is based on Buddhism: honour both Seon and Kyo traditions.

- Do not allow more temples unless they accord with the pungsu principles of Toson.

- The eldest son should succeed to the throne. If he is unworthy choose the next. If he too is unworthy, choose the next, and so on down the list.

- We have always followed Tang China; do not imitate the Khitan.

- The state is founded on good pungsu and the site of Pyongyang is crucial. Visit there every fourth year for 100 days.

- Maintain the Palgwan-hoe and Yondung-hoe festivals.

- Rule like the classic kings, with fairness, judiciously taking advice and not overtaxing the people.

- South of the Cha Pass and beyond the Geum river the people are as difficult as the terrain. Do not give them major appointments or marry them into the royal family.

- Practise no favouritism, pay fair emoluments, and always take care of the army.

- Study the ancient kings of China and keep the classic 'No Complacency' as your motto.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.