The Three Kingdoms Period of ancient Korea (57 BCE – 668 CE) is so-called because it was dominated by the three kingdoms of Baekje (Paekche), Goguryeo (Koguryo), and Silla. There was also, though, a fourth entity, the Gaya (Kaya) confederation at the southern tip of the Korean peninsula. These four states were in constant rivalry, and so they formed ever-changing alliances one with another and with the two dominant regional powers of China and Japan. Eventually, the Silla kingdom, with significant Tang Dynasty aid, would come to dominate and in the late 7th century CE form a single state, the Unified Silla Kingdom.

Historical Overview

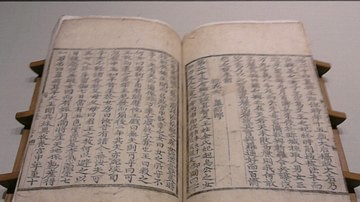

All of the kingdoms began from local tribes who settled and built fortified towns. These then grouped together to form single political entities. According to a tradition based on the 12th-century CE Samguk sagi ('Historical Records of the Three States'), this happened from the 1st century BCE, but modern historians prefer the 2nd or 3rd century CE (or even later) as a more accurate date for when the states could be described as having more centralised governments.

In the 2nd to 3rd century CE Goguryeo began to expand its territory by conquering the northern Chinese commanderies but suffered two serious setbacks in the mid-4th century CE when Murong Huang invaded from China and sacked Gungnae, taking 50,000 inhabitants prisoner (342 CE). Then the Baekje king Guenchogo, having already conquered the Mahan federation, attacked Pyongyang and killed king Gogugwon (371 CE). The Baekje were prospering due to their fertile agricultural lands and strong trade links with both China and Japan via the Yellow Sea and South Sea.

The defeat to Baekje in 371 CE had driven Goguryeo to form an alliance with Silla which set the foundations for a prosperous 5th century CE under the reign of Gwanggaeto (391-413), who lived up to his title of 'broad expander of domain' and permitted Goguryeo to dominate northern Korea, most of Manchuria, and a portion of Inner Mongolia. A new capital was made at Pyongyang in 427 CE while military success continued when Hansong (modern Gwangju), the Baekje capital, was sacked in 475 CE, and king Gaero executed.

Baekje formed an alliance with the Silla kingdom between 433 and 553 CE. Silla, during the reign of king Beopheung (r. 514-540 CE), achieved a much greater degree of centralisation. It had a splendid capital at Geumseong (Gyeongju) and was prospering on the eastern coast due to agricultural innovations such as oxen-drawn ploughs and irrigation systems, as well as an abundance of natural resources, especially gold and iron. The Baekje-Silla alliance, however, did not prevent Goguryeo gaining control of 90% of ancient Korea.

The Cinderella of the Three Kingdoms period was the Gaya confederation deep in the south of the peninsula. Unlike the other states, it never developed into a fully centralised kingdom partly because it was squeezed by its two more dominant neighbours Baekje and Silla. It did benefit from rich iron ore deposits, but in the mid-4th century CE Gaya was attacked by Baekje and then Silla flexed its muscles and captured the chief city-state Geumgwan Gaya (Bon-Gaya) in 532 CE. Other Gaya cities soon fell and by 562 CE the state was no more.

Meanwhile, Baekje's alliance with Silla came to a dramatic end when the latter occupied the lower Han River valley. In 554 CE, at the battle at Gwansan Fortress (modern Okcheon) Baekje tried to reclaim its lost territory, but their 30,000-strong army was defeated and King Seong killed. This move gave Silla access to the western coast and the Yellow Sea, providing the possibility to forge greater links with China.

Things were still going well in the 7th century CE for Goguryeo when their general Eulji Mundeok won a great victory at the battle of the Salsu River in 612 CE, defeating a massive invading Chinese Sui army. Two more attacks were defeated, and a 480-km (300 miles) long defensive wall was built in 628 CE so as to deter any further Chinese ambitions. This did not stop the Tang Dynasty – ambitious to play off these troublesome southern kingdoms against themselves – forming an army and naval force and attacking Goguryeo in 644 CE, but the great general Yang Manchun once again brought victory to the Koreans.

Goguryeo joined forces with Baekje against the Silla in 642 CE and conquered Daeya-song (modern Hapchon) and around 40 border fortresses. The Tangs had not given up in the north, though, and more attacks followed which eventually Goguryeo, weakened by the constant necessity for defence and by its own internal divisions, was unable to resist. Pyongyang was besieged in 661 and 667 CE by a Tang army, and this time, the city fell and with it the state of Goguryeo. In 668 CE the Goguryeo king Bojang (r. 642-668 CE) was removed to China along with 200,000 of his subjects in a forced resettlement programme.

Baekje was not faring any better than Goguryeo. The kingdom failed to tempt aid from Japan and could not prevent the fall of their capital Sabi when attacked by a joint Tang and Silla force on land and sea in 660 CE. A Silla army of 50,000 led by the general Kim Yu-sin and a naval force of 130,000 men sent by the Tang emperor Gaozong proved more than enough to crush the Baekje army. Uija, the last Baekje king, was taken prisoner to China, and the kingdom followed the way of Gaya and Goguryeo. By 668 CE Silla, after dealing with the Tang army left to govern the Chinese provinces which Goguryeo and Baekje had become, was in control of all of Korea, establishing what became known as the Unified Silla Kingdom.

Government & Social Classes

All of the states in this period had a similar system of government and social organisation. A monarch ruled with the aid of senior administrative officials drawn from a landed aristocracy. Government appointed officials administered the provinces with the aid of local tribal leaders. The majority of the population were landed peasantry and the state extracted a tax from them, which was usually payable in kind. The state could also oblige citizens to fight in the army or work on government projects such as building fortifications. At the very bottom of the social ladder were slaves (typically prisoners of war or those in serious debt) and criminals, who were forced to work on the estates of the aristocracy. Society was rigidly divided into social ranks, epitomised by the Silla sacred bone rank system, which was based on birth and dictated one's work possibilities, tax obligations, and even the clothes one could wear or the utensils one could use.

Relations with China & Japan

Despite the conflicts between China and the various Korean states over the centuries, the two nations were frequent trading partners. Iron, gold, and horses went to China, and silk, tea, and writing materials came in the other direction. There were close cultural ties too, with the Koreans adopting the Chinese writing system, the Chinese kingly title of wang, Chinese coinage, literature, burial practices, and elements of art. The Korean states, traditionally practitioners of shamanism, adopted first Confucianism, then Taoism and Buddhism from China, making the latter the official state religion.

Relations with the Wa (Wae) of Japan were particularly strong in the Gaya confederation. The latter was the more advanced culture and exported large quantities of iron, but just how much one state influenced or even controlled the other is still debated by scholars and clouded by national bias. Baekje culture was exported to Japan, especially via teachers, scholars, and artists, who also spread there Chinese culture such as the classic texts of Confucius.

Three Kingdoms Art

The art of the Baekje kingdom is generally considered the finest of the Three Kingdoms, but unfortunately for posterity, this kingdom provides the fewest artefacts having suffered the greatest destruction thanks to warfare and looting. Gaya and Goguryeo have suffered a similar fate, especially as their tombs had easily accessible entrances. The more enclosed tombs of Silla have been a better source of art objects from the Three Kingdoms period.

High-fired grey stoneware was produced by the Baekje, Gaya, and Silla kingdoms (little Goguryeo pottery survives). Typical forms are the stemmed cup, bowls with wide stands (kobae), horned cups, tall bulbous vases, and figure-vessels representing animals, boats, temples, and warriors. Ceramics were decorated with incisions, applied additional clay pieces, and by cutting away the clay to create a latticework effect.

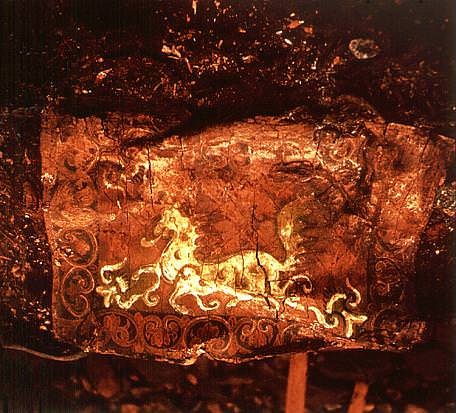

Tomb-painting is best seen in the tombs of Goguryeo. Over 80 of them have chambers decorated with brightly painted scenes of everyday life, portraits of the occupants, and mythical creatures. The paintings were made by applying the paint either directly onto the stone wall or onto a lime plaster base.

Gilt-bronze work was a typical medium of the region, perhaps best seen in the Baekje incense burner from near Sabi which represents a celestial mountain supported by a dragon and topped by a phoenix. Buddhist art was popular throughout the peninsula, and gilt-bronze was used to produce expressive statuettes of Buddha, Maitreya (the coming Buddha), and bodhisattvas. Baekje artists also sculpted cliff faces to represent the Buddha such as at Seosan. Another use of gilt-bronze was in royal crowns, which were also made in sheet-gold, most famously by the Silla kingdom. These have trees and stag-like branches, which represent a link with shamanism. Gold crowns and jewellery of all kinds were made using goldwork techniques such as wiring and granulation. Jade, often carved into crescent moon shapes, was a popular form of embellishment for these glittering adornments.

Three Kingdoms Architecture

Unfortunately, there are few surviving buildings from the Three Kingdoms period. However, archaeology and surviving tombs and their wall-paintings have permitted historians to identify the principal characteristics of palace and temple architecture throughout our period. These characteristics include tiled roofs which slope out and upwards at the corners, wooden and stone columns, interior paper-wall partitions, inner courtyards and gardens, and the whole placed on a raised platform. Harmoniously blending the structure into the immediate natural environment was another important consideration for Korean architects. The 7th-century CE Miruk temple at Iksan (now lost) is worth special mention. Built by the Baekje king Mu, it was the largest Buddhist temple in East Asia and had two stone pagodas and one in wood. One stone pagoda survives, albeit with only six of its original 7-9 storeys.

There are remains of Goguryeo fortification walls which had gates and towers from Tonggou, Fushun, and Pyongyang. Excavations have revealed that the latter also had very large buildings measuring up to 80 x 30 m and palaces with gardens which had artificial hills and lakes. Buildings were decorated with impressed roof tiles carrying lotus flower and demon mask designs.

An unusual structure is the mid-7th century CE Cheomseongdae observatory at the Silla capital of Gyeongju. Nine metres tall, it acted like a sundial but also has a south-facing window which captures the sun's rays on the interior floor on each equinox. It is the oldest surviving observatory in East Asia.

Tombs abound, with more than 10,000 from Goguryeo alone. These first took the form of cairns built using stone river cobbles (Goguryeo) or pits set into natural mounds (Gaya and Silla), then cut-block pyramids, and finally earth mounds within which were built stone chambers (or brick in the case of Baekje), which all had a horizontal entrance except those of the Silla which had no entrance. The tombs show various architectural features like corbelled roofing, octagonal pillars, and pivoted stone doors. One of the largest such mound tombs, actually composed of two mounds and containing a Silla king and queen, is the Great Tomb of Hwangnam. Dating to the 5-7th century CE, it measures 80 x 120 m, and its mounds are 22 and 23 m high. Another famous example is at Gungnae (modern Tonggou) and thought to be that of the Goguryeo king Gwanggaeto the Great (r. 391–412 CE). 75 metres long and using blocks measuring 3 x 5 metres, it also has four smaller dolmen-like structures at each corner. Finally, the tomb of Baekje king Muryeong-Wang is worth a mention as within its huge earth mound there is a semicircular vault lined with hundreds of moulded bricks, many decorated with lotus flower and geometric designs. The structure, located near Gongju, dates to 525 CE, as indicated by an inscription plaque within the tomb.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.