The Unified Silla Kingdom (668- 935 CE) was the first dynasty to rule over the whole of the Korean peninsula. After centuries of battles with the other states of the Three Kingdoms Period (57 BCE - 668 CE) Silla benefitted from the help of the Chinese Tang Dynasty to finally defeat its rivals and form a unified Korean state. In the following century, the kingdom would flourish and produce some of the finest art and architecture yet seen in ancient Korea. In the 10th century CE Silla fell to the resurgent northern kingdom, now known as Goryeo, which would rule until 1392 CE.

The Unification of Korea

The Three Kingdoms period in Korea stretched from the 1st century BCE to the late 7th century CE and involved four political entities: the Kingdoms of Baekje (Paekche), Goguryeo (Koguryo), and Silla, and the Gaya (Kaya) confederation. At various times China also took an active interest in the region, especially under the Han, Sui, and Tang dynasties. In the 660s CE, with military aid from the Tangs, who were eager to have these troublesome southern kingdoms weaken themselves fighting against each other, the Silla kingdom was able to defeat their long-standing rivals. This still left the Tangs as a dangerous player in Korean affairs, but while they were preoccupied with a rising Tibet, Silla armies defeated the Chinese forces which remained in Korea in the battles at Maesosong (675 CE) and Kibolpo (676 CE).

Consolidation & Prosperity

The new state, referred to as the Unified Silla Kingdom (Tong-il Silla) to distinguish it from its smaller predecessor the Silla Kingdom (Ko-Silla - 'Old Silla'), controlled all of Korea as far north as the Daedong River. Their immediate northern neighbour was the unfriendly Balhae (Parhae) kingdom in Manchuria, which had been formed by exiles from the old Goguryeo kingdom and members of the semi-nomadic Malgal.

The Silla kings were now dominated by the Kim clan with only a handful of kings coming from other aristocratic families. To help unify the country politically ruling aristocrats from the fallen kingdoms were forcibly relocated to where they were less likely to stir up rebellion but given a status equal to their Silla counterparts. To further ensure loyalty, certain members of these aristocratic families were required to regularly present themselves at Geumseong (also then known as Seorabol and today as Gyeongju), still the capital city. Those individuals regarded as too dangerous to the state and prisoners of war were enslaved to work on the estates of the aristocracy, in manufacturing workshops, or on government building projects. The overall size of the slave population is suggested by the records that some aristocrats had as many as 3,000 slave workers.

The whole state was now divided into nine provinces (three in each of the old three kingdoms) and five secondary capitals. Each province (chu) was governed by a general commandant administrator with the title of chonggwan. The title was changed to todok (governor) in the 9th century CE. Each province had 117 prefectures (kun), each of which was further divided into 293 counties (hyon), with each one being composed of various villages and hamlets (chon) and those specially created settlements for undesired persons (hyang, so, and pugok). Every level had its own chief administrator, all of whom were regularly supervised by a government inspector or oesajong. A further measure to ensure local loyalties were maintained was to compel village headmen to send their eldest sons to work in the capital administration or military, a process known as (sangsuri).

Gyeongju became even more splendid in this period. It is described in the Samguk yusa collection of texts as having an astonishing 35 palaces, 55 streets, 1360 districts, and 178,936 houses. This would allow for a population of around 900,000. One palace was built on the shore of an artificial lake while another had watercourses running through it so that floating wine cups could be floated to guests. There were even palaces and gardens specifically for each of the four seasons with exotic flora and fauna. New temples were built or extended such as the massive Bulguksa (Temple of the Buddha Land) which rose from a lotus lake.

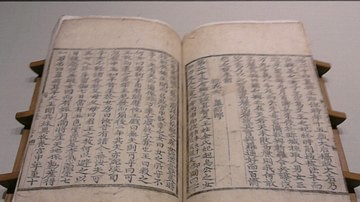

The wider kingdom prospered due to a thriving agricultural industry, which was made more productive via extensive irrigation projects, and trade throughout the East China Sea. The prolonged absence of war also meant that the arts and sciences flourished as never before. Architecture, sculpture, metalwork, mathematics, and astronomy were particular areas of excellence. History became an important study, and it was at this time that improvements were made in woodblock printing.

Relations with China

Despite the Silla kingdom's refusal to become just another Chinese province, relations with China were not soured, in fact, the young Korean state became a loyal ally. The influence of Chinese culture continued to be significant, as it had been throughout the previous Three Kingdoms period. Both Confucianism and Buddhism remained an important part of the Silla education system, and the latter was still the official state religion, practised by all levels of society. The most famous of all Buddhist scholar-monks belongs to this period – Wonyho, who popularised the faith in the 7th century CE. If anything Confucianism became stronger in the Unified Silla with a National Confucian Academy established in 682 CE and an examination for state administrators introduced in 788 CE.

There was a healthy trade between the two states too with Chinese luxury goods such as silk, books, tea, and art being imported while Korea exported metals (especially gold and silver), ginseng, hemp goods, manufactured goods, horses, and sent students and scholars to China. There were even Silla controlled trading areas in Chinese territory, such was the volume of trade. Relations were also maintained with southern Japan, especially in the Nara and Heian periods. Arab merchants, who brought spices, carpets, and jewellery, were another point of contact with the wider world. Finally, glass finds within Korea include Roman, Sasanian, and Syrian vessels attesting to a thriving trade network throughout the period.

Silla Art

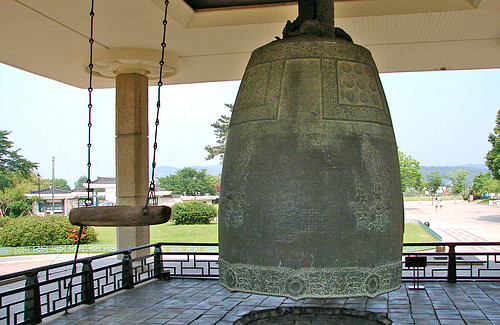

Metalwork continued to be a fine Silla art, best seen in the gold crowns from various tombs, but the Unified Period also saw a new art form develop, that of making large bronze-cast bells (pomjong) which were used in Buddhist temples to announce services. The largest example is from Bongdeoksa, also known as the Emille Bell, which was cast in 771 CE to honour King Seongdeok. 3.3 metres tall and over 2.2 metres in diameter, it is decorated with lotus flowers and heavenly beings with a suspension loop in the form of a dragon. Weighing almost 19 tons, the bell is now on display in the Gyeongju National Museum. Another popular art form was bronze-cast sculpture, especially Buddhist figures which were gilded and polished. Monumental figures were also made using cast iron with parts made separately and then assembled and painted or covered in plaster. Yet another use of bronze was to manufacture intricate boxes to store relics and important texts. These are known as a sarira and could take the form of pagodas and trees.

Unified Silla pottery displays a marked influence of Buddhism. Cremation necessitated the manufacture of urns for ashes, and Buddhist motifs prevail in stamped decoration such as lotus flowers and clouds, often with lotus buds for lid handles. Everyday pottery was left undecorated, but special pieces show a greater density of decoration than previously, and there is the first ash glaze which would develop into the later celadon ceramics of the Goryeo period. Tombs have also revealed pottery figures and models, which include servants, warriors, and animals.

Other surviving examples of Unified Silla artistry come in the form of stone lanterns, roof tiles with hideous faces to ward off evil spirits, floor tiles decorated with lotus petals (increasing from the standard 6-8 of previous periods to either 16 or 32), and calligraphy (unfortunately, no paper examples survive) by such greats as Kim Saeng (again no works exist today), and seen in the stonework of the Hwaom sutra passages at the Hwaeomsa temple in the South Jeolla province.

Silla Architecture

We know from descriptions that the palaces of Gyeongju had their own gardens and lakes, but, sadly, all that survives of the buildings themselves are decorative floor tiles. Notable surviving structures at the capital include two stone pagodas – the Dabotap and Seokgatap – which both date to the 8th century CE, traditionally 751 CE. Stone pagodas are Korea's unique contribution to Buddhist architecture (in Japan they are of wood and in China of brick), and this pair was originally part of the magnificent 8th century CE Bulguksa Temple, which now stands restored but only a fraction of its original size.

One of the outstanding stone structures from the Unified Silla period is the Buddhist Seokguram Grotto temple east of Gyeongju. Constructed between 751 and 774 CE, it contains a circular domed inner chamber within which is a massive 3.45 metre high seated Buddha. The walls are decorated with 41 large figure-sculptures of disciples and bodhisattvas.

From the 7th century CE onwards, Silla tombs became more like the earlier tombs of the Goguryeo and Baekje with a horizontal entrance and a smaller earth mound on top, which was then faced with stone slabs. The slabs are frequently decorated with relief carvings of the twelve animals of the oriental zodiac. Each figure carries a weapon and so offers symbolic protection of the tomb. Two of the finest examples are the tombs of the general Kim Yu-sin (7th century CE) and King Wonseong (8th century CE) at Bongdeoksa. Stupas were built too, the large domed buildings built as memorials to particularly renowned Buddhist monks. The most famous stupa is that of Toyun, founder of the Saja-san sect, at the Ssanbong-sa temple at Hwasun while the oldest, built in 790 CE, commemorates Monk Yomgo.

Decline

The state began a slow decline from the 8th century CE, largely due to the rigidity of its class structure. This was based on the bone rank system, the strict social classification of entitlements and obligations dictated by one's birth, which continued to operate as in the old Silla kingdom and which completely dominated the workings of the aristocracy and state administration. Not only did the lack of opportunity to rise above the class of one's birth create a stagnation of ideas and innovations but the aristocracy began, too, to resent the power of the king. At the other end of the social ladder, the peasantry grew more and more resentful of the incessant taxes levied upon them. On top of that, local landed aristocrats (songju) became ever more difficult to control from Gyeongju. The state was falling apart from within.

Two individuals would cause particular trouble for the Silla kings. One Gyeon Hwon, a peasant leader, took advantage of the political unrest in 892 CE and formed a revival of the old Baekje kingdom in the south-west portion of the peninsula. Meanwhile, an aristocratic-Buddhist monk leader, Gung Ye, declared a new Goguryeo state in the north in 901 CE, known as Later Goguryeo. There then followed another messy power struggle for control of the peninsula just as there had been in the Three Kingdoms period. Kyon Hwon attacked Gyeongju in 927 CE while Gung Ye's unpopular and fanatical tyranny led to his death at the hands of his own people. He was succeeded by his first minister, the able Wang Geon, in 918 CE who attacked Later Baekje, now beset by leadership in-fighting, and then Silla. The last Silla king, Gyeongsun, surrendered in 935 CE and left Wang Kon to unify the country once again but under a new name, the Goryeo (Koryo) Dynasty, which would rule Korea from 918 CE to 1392 CE.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.