Jang Bogo (aka Chang Pogo or Gungbok) was a powerful Korean warlord, naval commander, and merchant who came to monopolise maritime trade in northeast Asia to such a degree that he was known as the 'King of the Yellow Sea' during the first half of the 9th century CE. His exploits have gained him a legendary status which he still enjoys in Korea today.

Early Life

Jang Bogo's life and trading activities are described in the Account of a Pilgrimage to Tang in Search of the Law (Nyu To kyuho junrei koki) by the Japanese scholar-monk Ennin (aka Jikaku, 794-864 CE). The account contains a passage describing a voyage in one of Jang's naval vessels in 840 CE to the Buddhist monastery at Shandong. Amongst other sources are the works of the Chinese poet Du Mu, and it is interesting here to note that, indeed, most of the ancient accounts of Jang's exploits come from Chinese and Japanese sources, indicating his fame throughout East Asia. This has led the historian Kyung Moon Hwang to state, "there might not have been a Korean historical figure better-known outside northeast Asia until the twentieth century" (28).

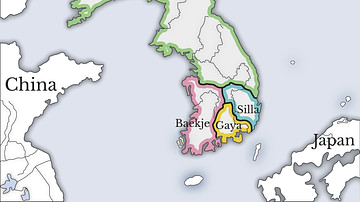

Jang was born, perhaps in 788 CE, into a modest family in the town of Cheonghae (Wando island), located off the south-west coast of the Unified Silla Kingdom of ancient Korea. In his early career, we are informed that Jang served as an officer in the army of the Tang dynasty, like many of his Silla contemporaries, and fought in the lower Huai River basin of China.

Garrison Commander at Cheonghae

Returning to Korea in 828 CE, Jang requested from the Silla king permission to establish a garrison at Cheonghae. Jang argued that only a permanent military presence could eradicate the troublesome Chinese pirates which were plaguing the East Asian seas at that time and provide naval escorts for Koreans travelling by sea who were being captured by the pirates and sold into slavery in China. His proposal was accepted by King Heungdeok, and Jang was made its commander, a position he held until 846 CE. It may be that the royal approval was a mere formality as by then Jang already possessed a large private navy of his own, but a fortress was constructed, known as Cheonghaejin, which housed 10,000 soldiers.

From his base, Jang's naval fleet could control all maritime trade between China and Korea across the Yellow Sea and South Sea as well as commerce to and from ancient Japan. Goods shipped would have included precious metals, manufactured goods from furniture to weapons, silk, tea, and ginseng. In addition, the trade network of the time established contact with traders from afar afield as Arabia and east Africa who brought exotic spices, carpets, and animal products.

Once he had cleared the area of piracy, and with his leadership of the Korean community on the Shandong peninsula, Jang established a lucrative monopoly on the region's ceramics trade. He may well have contributed to the popularity of Chinese porcelain in the wider world and facilitated technology improvements in Korea's own potteries. Jang is also credited with establishing the Buddhist temple of Pophwawon and its monastery at Shandong which had 28 monks and nuns. Not only did this meet the religious needs of the Silla expatriates but it also served as his diplomatic and commercial headquarters.

Silla Politics & Assassination

In 839 CE Jang backed Gim Ujing and, attacking the capital of Gyeongju, helped him ascend the throne of the Unified Silla Kingdom as King Sinmu. In gratitude, the king gave Jang the impressive title of Grand General of Cheonghae. Unfortunately, Sinmu would only reign for a year, and so Jang sought to maintain his influence at court by having his daughter marry the son of Sinmu's successor, King Munseong to become his second queen. These overtures proved unsuccessful and Jang was murdered in 846 CE by an assassin known as Yeomjang, hired by his aristocratic political rivals who, no doubt, saw him as a commoner who had gained too much power for their own good. The Cheonghae garrison, having served its purpose, was disbanded in 851 CE.

Jang's reputation has lived on, though, not only in the following centuries thanks to ancient writers but also in modern Korea where there has been a renewed interest in national historical heroes. Museums, TV shows, submarines, and even an Antarctic research station have been dedicated to this legendary figure from the golden era when Korea dominated the trade networks of northeast Asia.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.