Karakorum (aka Qaraqorum, modern name: Harhorin) is located in the Orkhon Valley of central Mongolia and was the capital of the Mongol Empire from 1235 to 1263. Ogedei Khan (r. 1229-1241) ordered its construction, and had a walled palace built. He made the city a thriving trade centre by attracting merchants of all nationalities and faiths there.

Karakorum was later replaced as the Mongol capital by Daidu (Beijing) and Xanadu. The city then went into a long decline but is today a major archaeological site and the location of an important 16th-century Buddhist monastery, Erdene Zuu.

Location

The imperial court of the khans had no fixed home as the nomadic roots of the Mongol leaders and their frequent military campaigns meant that they continued to move from camp to camp across their vast empire. Nevertheless, the Mongol administration urgently needed a capital city where revenue could be accumulated and some attempt at a centralised government could be made to govern their conquered territories. Consequently, Ogedei called in skilled artisans, masons, and craftworkers from Persia to China and ordered the building of a walled capital in 1235.

Karakorum is located in the Orkhon Valley of central Mongolia, 400 km southwest of the present capital of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar. The choice of location was perhaps influenced by its traditional use as a gathering ground and by Genghis Khan (r. 1162/67-1227), who had used the site as a semi-permanent campsite some decades before and may even have earmarked it as a candidate for a future capital in 1220. Long before that the Uyghur Turks had had their capital Qarabalghasun in the Orkhon Valley in the 8th-9th century. Apart from being centrally located within the Mongol Empire as it was in 1235, the site was blessed with a good water supply, nearby mountains for varied pasture for livestock and fresh winds that kept mosquitoes away.

The name Karakorum (often spelt Qaraqorum or Caracorum) may derive from a river of that name which ran to the west of the city, although this may be a misinterpretation by later scholars. An alternative origin of the name is that it derives from the Mongol tradition of holding winter feasts or qurim, a custom especially associated with the 'black' or qara Mongols (those who were not of the elite). A third theory is that the name means 'Black Rock' or 'Black Walls.'

Due to its remoteness and situation in grasslands not suitable for agriculture, hundreds of cartloads of food had to be transported into the city daily in order to feed its population. Despite this drawback, the city was part of the excellent Mongol road and messenger network, the Yam, and it did indeed become an important logistics centre and repository of the empire's resources. In addition, many merchants travelled there, encouraged by its location on the Silk Roads and the khan's generous prices for their goods - often double the figures paid anywhere else. Consequently, the city soon boasted large and regular markets where everything from goats to rent boys were bought and sold.

Features

Karakorum was not large, only 10,000 people at its height resided there (although some scholars prefer a figure nearer 30,000), and this led to a rather disparaging description of it by the historian William of Rubruck (c. 1220-1293). The Franciscan missionary, who travelled to the site in the 1250s, compared it unfavourably with western capitals and described it as no more impressive than a village suburb of medieval Paris.

The city might have been compact but it was cosmopolitan with residents including Mongols, Steppe tribes, Han Chinese, Persians, Armenians, and captives from Europe who included a master goldsmith from Paris named William Buchier, a woman from Metz, one Paquette, and an Englishman known only as Basil. There were, too, scribes and translators from diverse Asian nations to work in the bureaucracy, and official representatives from various foreign courts such as the Sultanates of Rum and India. This diversity was reflected in the various religions practised there and, in time, the construction of many fine stone buildings by followers of Taoism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity. Great storehouses were built and filled with treasures and produce taken as tax from peoples the Mongols had conquered. With them, a huge bureaucracy, perhaps involving one-third of the city's population, developed to keep track of everything, and there were law courts to hear special cases from anywhere in the empire and workshops where raw materials were worked into precious goods.

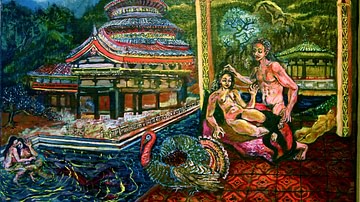

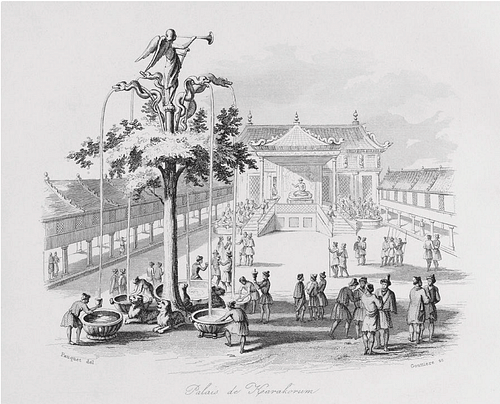

Ogedei Khan visited occasionally, and he had a palace built for those times when he did stop by. This palatial residence featured gilded columns, pavilions, gold and silver basins, and a wine cellar, and its walls were decorated with fine paintings by Khitan artists. One famous feature of the palace served one of Ogedei's passions. The Great Khan was known for his prodigious drinking bouts, and he had a huge silver fountain shaped like a tree set up in his palace that served all manner of alcoholic beverages from fantastically-shaped spouts. William of Rubruck, rather more impressed with the tree than the city, gives the following lengthy description:

In the entry of this great palace, it being unseemly to bring in there skins of milk and other drinks, master William the Parisian had made for him [the Great Khan] a great silver tree, and its roots are four lions of silver, each with a conduit through it, and all belching forth white milk of mares [the alcoholic drink called koumiss]. And four conduits are led inside the tree to its tops, which are bent downward, and on each of these is also a gilded serpent, whose tail twines round the tree. And from one of these pipes flows wine, from another cara cosmos, or clarified mare's milk, from another bal, a drink made with honey, and from another rice mead, which is called terracina; and for each liquor there is a special silver bowl at the foot of the tree to receive it. Between these four conduits in the top, he made an angel holding a trumpet, and underneath the tree he made a vault in which a man can be hid. And pipes go up through the heart of the tree to the angel. In the first place he made bellows, but they did not give enough wind. Outside the palace is a cellar in which the liquors are stored, and there are servants all ready to pour them out when they hear the angel trumpeting. and there are branches of silver on the tree, and leaves and fruit. When then drink is wanted, the head butler cries to the angel to blow his trumpet. Then he who is concealed in the vault, hearing this blows with all his might in the pipe leading to the angel, and the angel places the trumpet to his mouth, and blows the trumpet right loudly. Then the servants who are in the cellar, hearing this, pour the different liquors into the proper conduits, and the conduits lead them down into the bowls prepared for that, and then the butlers draw it and carry it to the palace to the men and women.

(quoted in Lane, 156-7)

This ingenious device perhaps proved too much of a temptation as Ogedei Khan, aged 56, died in Karakorum on 11 December 1241 after a heavy drinking bout likely brought on a stroke or sudden organ failure.

A Political Pawn

In 1263 Karakorum was replaced as the Mongol capital by Xanadu (aka Shangdu), located in Inner Mongolia. The latter would itself be replaced by Daidu (Beijing) in 1273, although Xanadu would continue to function as the Mongol summer capital. As Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294) bit off larger and larger chunks of Song Dynasty China (960-1279) from 1268 onwards, a more centrally-placed capital was required. Karakorum also had unpleasant associations for Kublai because his great rival as supreme ruler of the Mongols, Ariq Boke (1219-1266), had used the original capital as his base before Kublai captured it in 1262.

There was one problem with Kublai moving his capital further east and that was it became more difficult for him to maintain control of western Asia. Another rival, Kaidu (grandson of Ogedei Khan), mobilised towards Karakorum in 1288 and so Kublai was obliged to send one of his best generals, Bayan to garrison the city from 1290 to 1293.

Later History

Karakorum was not totally abandoned and, even if it was no longer politically or commercially important, it remained a potent symbol of the Mongol control of Asia. After the fall of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) in China, the last Yuan emperor, Toghon Temur (r. 1333-1368) fled to the old capital where he died in 1370. The Mongols might have lost China but at least in 1372 an army of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) was defeated near Karakorum, putting an end to any Chinese ambitions in Mongolia. Over the centuries, Karakorum suffered pillaging of its stonework for rebuilding elsewhere, notably the 1586 Buddhist monastery at Erdene Zuu.

Excavations have been carried out, first by Russian archaeologists in 1899, and again in 1948-9 and, more recently, by Mongol authorities, especially at the palace of Ogedei. We know now that the palace was once on a raised platform and surrounded by a wall, it had private apartments, treasuries and storehouses, and an area in one corner for the khan to erect his yurts (gers), the traditional tents of the Mongols. There is evidence that other parts of the city were also used as a site for yurt camps, illustrating that in the mid-13th century, the Mongol elite still continued their nomadic traditions.

The largest single surviving architectural piece from Karakorum is a massive stone turtle from the palace which would have once had a stela on its back. Archaeology has also revealed the remains of a mosque and a Buddhist temple as well as craft stalls. Further indicators of Karakorum's wealth and position as a trade hub include finds of administrative seals, ornate dragon-decorated tiles, copper mirrors, gold objects like finely worked jewellery and high-quality Chinese ceramics. Many of these finds can be seen today in the Kharkhorin Museum, Kharkhorin, Mongolia.