Lycia is a mountainous region in south-west Anatolia (also known as Asia Minor, modern-day Turkey). The earliest references to Lycia can be traced through Hittite texts to sometime before 1200 BCE, where it is known as the Lukka Lands. The city is mentioned in both Hittite and Egyptian texts, where they the Lycians are associated with a group known as the Sea Peoples. Lycia is also recorded as having contact with both the Greek and Roman civilizations, granting the region a recorded inhabited lifespan of over 2,000 years.

Mythological Origins

Lycia appears as an important figure in Greek mythology and is frequently referenced. The historian Herodotus records one version of Lycian descent, claiming that the inhabitants of Lycia were originally from Crete (1.173.3). He relates their origin to a royal dispute between the two sons of Europa, namely Sarpedon and Minos. Sarpedon, the defeated brother, was cast out but went on to found Lycia. During this period, Herodotus claims that the settlement was known as Termilae. It was not until a man called Lycus, who was banished from Athens, arrived at Termilae that the site was then known as Lycia.

Lycia also appears in the story of Bellerophon, who became the king after Iobates, while it also participated in the Trojan War on the side of the Trojans. Sarpedon and Glaucus were the two most important Lycian leaders in the war and were granted extensive lands for their efforts in Homer's Iliad.

Geography

Lycia is a mountainous region lying on the southwest coast of modern Turkey. In the ancient world, the site appears to have had less than 100 hundred settlements. Some of these settlements are mentioned frequently in Greek and Latin literature, such as Xanthos, Patara, and Olympos. The region is often associated with the settlement of Caria, located on the north border of Lycia. Ancient references to the Lycians claim that their customs are like the Carians, suggesting that the sites were occupied by one ethnic group. As both cities are referenced together in Homer's Iliad, Lycia and Caria may have had some form of ethnic relations.

The region of Lycia is also associated with the name Lukka Lands, a site referenced in both Hittite and Egyptian literature. These references to a region called the Lukka Lands have provided historians with an alternative version of Lycian heritage. It is now widely believed among historians that this location in Hittite texts was indeed the later site of Lycia.

Historical Overview

The first references to Lycia refer to the Lukka Lands in the late Bronze Age. Whilst the Lycians themselves created no literary record, they appear in both Hittite and Egyptian literature during this period. Both kingdoms record the Lycians as relatively hostile and rebellious peoples. Under the reign of the Suppiluliumas, in the 14th century BCE, the Lukka Lands remain in a state of constant rebellion. As the Lukka Lands were able to oppose the dominance of the Hittites, it is thought that they held a strong settlement and military influence.

In Egyptian sources, the Lukka peoples are recorded in a confederacy called the 'Sea Peoples'. The Sea Peoples were naval raiders active between c. 1276-1178 BCE. Lukka is listed along with several other settlements for their involvement in these naval raids on tablets from Tel-el-Amarna in Egypt. These raids are attested throughout the reigns of Ramesses II (The Great, 1279-1213 BCE), his son Merenptah (1213-1203 BCE), and Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE). Again this hostile contact with Egypt suggests that Lukka Lands held a strong military influence in the region.

After the collapse of the Hittite Empire, Lycia emerged as an independent "Neo-Hittite" kingdom. Homer's Iliad and Herodotus' Historia were both composed by Greeks from Anatolia during this period of independence. Their perspectives of Anatolia are invaluable for creating an understanding of Lycian society. Homer's Iliad provides the earliest appearance of the Lycians in Greek literature, in which the people of Lycia are recorded as allies of Priam and fighting at Troy (2.876-7).

The Lycians were also involved during the Persian Wars of the 5th century BCE. However, they appear allied with the Persians as they contributed 50 ships to the Persian fleet in 480 BCE. The Persians held control over Lycia from 546 BCE after they had overrun the central city of Xanthus. During the aftermath of the Persian Wars, Lycia appears as a subject of the Delian League but reverted to Persian control soon after. In the 4th century BCE, they were ruled by dynasts, most notably the figure Pericles. However, this governance readily submitted to Alexander the Great during his expansion into the region (334-323 BCE).

After the death of Alexander the Great (323 BCE), Lycia was then handed to Ptolemy I. It was later conquered by Antiochus III in 197 BCE during the period of turbulence following Alexander's death (also known as the Wars of the Diadochi or Successor Wars). After the Battle of Magnesia in 189 BCE, Antiochus III was defeated and so Lycia was given by the Romans to Rhodes. The Lycians resisted Rhodian control and in 177 BCE the Lycians sent an embassy to Rome complaining of the harsh Rhodian treatment. The issue was not resolved and the Lycians took up arms and remained in conflict until 167 BCE when the Senate decided to free Lycia and her neighbour Caria.

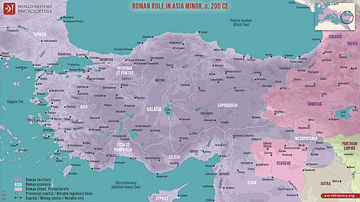

During the Roman civil wars (1st century BCE), the Lycians suffered from the plunders of Brutus and Cassius, who had assassinated Caesar. After the pair's defeat, Mark Antony was given control of the East, including Lycia. During this period Lycia was merely incorporated into Asia Minor. This, however, changed under the reign of Roman emperor Claudius (41-54 CE), who joined Lycia and the neighbouring Pamphylia in 43 CE. The two settlements shared a Roman governor, but in practice functioned rather differently.

Lycian Society

Herodotus notes something rather extraordinary about the Lycian culture. He claims that the Lycians adopted matrilineal descent, taking 'their names not from their fathers, but from their mothers' (1.173.4-5). This practice is the direct opposite of the Greeks, where the descent was traced through male lineage.

As already discussed, Herodotus did have a good knowledge of the history of the Anatolian region, including Lycian neighbours such as the Cretans and Carians. In addition to the comment regarding female descent, Herodotus claims that when a Lycian woman marries a slave her children will be allowed full rights. However, if a male citizen marries a female slave their children will be denied citizen rights. This again reinforces the notion that in Lycia, women were central to the society, reflected both in law and in the tracing of descent. Similar societies have been noted in Indian history, for example, Dravidian social order, where some parts of society were characterised by matriarchy and matrilineal succession. This practice was well attested throughout history, even as recently as the 19th century CE.

Whilst there is no conclusive evidence to confirm Herodotus' statement, there are suggestions elsewhere that establish the presence of matrilineal descent in Lycia. A similar claim is made by the 1st century BCE author Nikolaos Damaskenos. There has also been a collection of tomb inscriptions found, which have been interpreted by some scholars as evidence of matrilineal descent. However, this is very much contested by scholars.

Lycian Language

Lycian is an Indo-European language, in the Luwian subgroup of Anatolian languages. The Lycian language is documented on fewer than 200 inscriptions, several of these only comprising names from coinage. Their alphabet features 23 consonants and six vowels, which were written left to right in horizontal lines. The literary records of Lycia occur at the same time as the Persian occupation, 500 BCE - 300 BCE. After the Persian rule, Lycia adopted Greek as their main language and, therefore, there are no later Lycian inscriptions.

Many of these inscriptions come from funerary monuments, for example, the Tomb of Payava. Whilst the inscription is rather short, it demonstrates how the Lycian society used their language, which occurs most often in a funerary context. One of the better-known examples of Lycian inscriptions is that of the Xanthian Obelisk, which contains a trilingual text referring to a religious cult. The inscription sits upon a tomb in Xanthos and is sometimes referred to as the Inscribed Pillar of Xanthos.

Lycian Governance & Religion

Given a lack of written documentation, little is known about the exact governance of Lycia. However, sometime during the 4th century BCE, the Lycian League was formed. The League was the first democratic union known from history and was formed of elected representatives. Ancient writers appear to admire the League which linked the Lycian city-states within a political organization. The representatives would meet to discuss various issues such as trade rights and marriage laws. The male Lycian citizens who were residents or landowners could vote for their representatives in the Assembly on various matters.

The Lycian League's capital was at Patara, where it is still possible to see the remains of the assembly building. The Roman historian Livy also records that at Patara in the Temple of Apollo archives were kept relating to the league.

Apollo was a particularly important god for the Lycians, as his origin is believed to have been Anatolian. Artemis was also important for Lycia, as she was considered the Anatolian sister of Apollo. Both Apollo and Artemis had cult centres in Lycia, however, neither are as well attested as the goddess Leto. In Xanthus, the religious sanctuary known as Letoon appears to have been the most important for Lycians. Three temples are dedicated to Leto in this region, where the national festivals were held. Other shrines exist to Leto throughout the region, making her the most influential religious figure in Lycia.

Lycian Archaeology

There are a variety of impressive remains in Lycia, notably Lycian tombs. Over 1,000 rock-cut tombs can still be seen in modern-day Lycia. This phenomenon is noteworthy for quantity and quality, but also for their unique belief systems. The Lycians believed that the souls of their dead would be transported from the tombs to the afterworld by a winged siren-like creature, so placement on cliff edges and the coast was important.

The tombs are carved with protruding beams and are often several stories high, which often resemble houses. The funerary art and architecture in Lycian tombs relate to both Greek and Persian influences. Yet, rock-cut tombs are not exclusive to Lycia, for they have been found in other places in the Mediterranean, for example in Etruria. The most famous Lycian example of a rock-cut tomb is the Tomb of Amyntas at Telmessos. This tomb is the largest of its kind and resembles a temple-like structure, dating to around 350 BCE.