Georgia, lying at the junction of Europe and Asia, is a country of ancient myths with a rich and turbulent history. Home to the first European hominids and the birthplace of wine, Georgia's roots trace back to ancient civilisations. Throughout its history, the Caucasus region witnessed the influence of various empires and played a crucial role in transcontinental trade routes.

The most famous Georgian kingdom was Colchis, the mythical land of Medea and the Golden Fleece. It flourished from the 13th to the 6th century BCE, thanks to its strategic location along the Black Sea and its abundant natural resources.

Geography

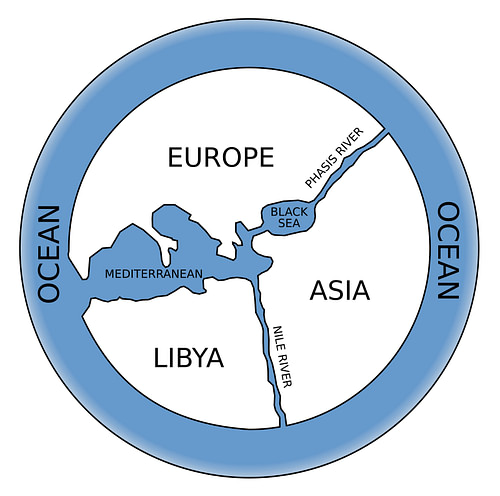

Georgia is between the Black Sea to the west and the Caspian Sea to the east. It is bordered by Russia to the north, Azerbaijan to the southeast, Armenia to the south, and Turkey to the southwest. The country lies mostly in the Caucasus Mountains, and its boundaries are partly defined by the Greater and Lesser Caucasus, two of the world's great mountain ranges and the highest peaks in Europe. Georgia has a diverse, fertile geography with extensive plains and rivers, navigable marshes, deep forests, mountains, and passes. Georgia has about 25,000 rivers. The largest river in western Georgia, the Phasis (now known as the Rioni River), was considered by ancient Greek geographers such as Anaximander of Miletus (l. c. 610 to c. 546 BCE) as the dividing line between Europe and Asia.

Wine & Metals

Georgia is one of the oldest wine-producing regions in the world. Winemaking can be traced back to the Neolithic period, over 8,000 years ago. Traditional vinification techniques involved using qvevris, large earthenware jars buried for fermentation and storage. This ancient method and the presence of 500 indigenous grape varieties contribute to the distinct character of Georgian wines.

The country's rich natural resources have also played an important role in the history of the South Caucasus. The development of metallurgy more than 5,000 years ago and some of the world’s first gold mines (dating to c. 3000 BCE) contributed to a vibrant trade network, connecting the Mediterranean with the Caucasus and beyond. Georgia had a flourishing bronze and iron industry and fluvial gold in mountainous Svaneti, where gold extraction using sheepskin originated. According to historical sources, the Kingdom of Colchis was rich in "gold sands,” and the indigenous Svans mined the rivers using special wooden vessels and sheepskins. The Svans still mine gold from rivers as they did in ancient times.

The Golden Fleece

In Greek mythology, the Golden Fleece was said to be in Colchis, an ancient region located on the eastern coast of the Black Sea in present-day Georgia. The Thessalian hero Jason and the Argonauts went on a quest to retrieve the Golden Fleece. The Argonautica is the epic tale of their adventures. Medea, a sorceress and princess of Colchis, assisted Jason during this quest. Medea fell in love with Jason and used her magical abilities to help him complete various challenges set by her father to obtain the Golden Fleece.

However, their story took a tragic turn. After returning to Greece, Jason marries another woman, which leads to a series of events where Medea seeks revenge. The most infamous act attributed to Medea is the murder of her children, born to Jason, as a form of revenge against him.

A Short Introduction to Ancient Georgia

Different highly developed societies existed within Georgia's territory during the Bronze Age. The emergence of advanced metallurgy, viticulture, farming, livestock-raising, and artistic craftsmanship characterised these successive cultures. From 3500 to 1600 BCE, Georgia was the heart of the Kura-Araxes and Trialeti cultures, which practised metallurgy and produced gold and silver artefacts of the highest artistic value.

Two early Georgian states, Colchis in the west and Iberia (or Kartli) in the east, rose during the classical period. Colchis extended along the eastern coast of the Black Sea, while Iberia encompassed Georgia's eastern and southwestern provinces. Both kingdoms stood on the peripheries of the great powers of antiquity: the Greek world to the west, the Assyrian and Persian Empires to the south, and the Scythians to the northwest. Colchis experienced influences from these neighbouring regions and thrived economically due to its strategic location along the Black Sea trade routes.

The Colchians were skilled artisans engaged in commerce, exporting valuable resources such as gold, timber, and slaves. Goldsmithing was particularly notable, and the abundance of gold in the region contributed to the wealth and reputation of Colchian craftsmanship. Colchis's economy also rested on agriculture, cattle breeding, and fishing. Much of the kingdom was built on the banks of the Phasis River, which flows into the eastern side of the Black Sea. The Colchian lowlands enjoyed a subtropical, warm and humid climate, creating good conditions for crop cultivation.

In the 6th century BCE, Milesian Greeks, looking for new markets, new resources, and agricultural opportunities, established trading posts (known as emporia) along the shores of the Black Sea. These Greek colonies led to a profound Hellenization of the Colchian elite, reflected in the mintage of local Graeco-Colchian coins and the influence of Hellenistic architecture on Colchian urban planning. After the 6th century BCE, Colchis was under the nominal suzerainty of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE), passed into the kingdom of Mithridates VI (120-63 BCE), and then came under the rule of Rome in the 1st century BCE together with Iberia after Pompey's victory in the Third Mithridatic War (66-65 BCE). Iberia became a vassal kingdom and Colchis the Roman province of Lazica.

From the 1st century CE, the Romans constructed forts along the coast at points where inland routes joined the sea. These permanent garrisons defended the Roman northeastern border (the Pontus Limes). Together with veterans, soldiers' families, servants, and others, these forts formed settlements that could become towns and cities. Cultural exchanges occurred through trade, diplomatic relations, and the movement of people, contributing to a blend of local and Roman influences.

The Georgian kingdoms were often caught in the power struggles between the Roman and the Sassanian Empires, culminating in the Lazic War from 541 to 562 CE, and experienced periods of Byzantine and Persian dominance. Christianity spread in the early 4th century CE when Saint Nino (l. c. 280-332 CE) converted King Mirian III (r. 284-361 CE) and Queen Nana of Iberia (r. 292-361 CE), making Georgia one of the earliest nations to adopt Christianity as the state religion. In the later centuries of the Roman and Byzantine periods, Colchis faced challenges from various invasions, including those by nomadic tribes and the expanding Arab Caliphate. These invasions and internal strife contributed to the decline of the region's political stability and economic prosperity.

UNESCO has recognised Georgia's most significant landmarks: the ancient city and former capital Mtskheta, Gelati Monastery, and the mountainous region of Upper Svaneti, with a further fourteen on the tentative list. Other significant archaeological sites are well-preserved.

Here are seven ancient sites to explore while visiting Georgia.

Vani Archaeological Museum & Site

Vani is one of the most famous sites in Colchis. It is located 40 kilometres (24 mi) southwest of Kutaisi, the residence of the mythical King Aeetes and today the country's third largest city. Established in a fertile region at the Sulori and Rioni Rivers confluence, Vani was a small settlement serving as the Colchis kingdom's religious centre between the 8th and 1st century BCE. It spread on a hill over three terraces, flanked on two sides by deep ravines that served as natural defences. The city's ancient name is not known with certainty, but scholars have argued that Surium, mentioned by Pliny the Elder (l. 23-79 CE), could have been its original name.

Vani's size and wealth increased dramatically from the 6th century to the end of the 4th century BCE. During this period, the city became the political and administrative centre of the area. Vani was also the burial place for the local elite, who dominated an extremely hierarchical society. Archaeologists have uncovered 28 burials dating to c. 450-250 BCE, notable for the splendour of their goods. Various vessels were deposited with the dead, including Greek and Persian imports, providing evidence for banqueting in the local funerary rituals. The richest graves had impressive gold jewellery, including elaborate Colchian gold hair ornaments and appliques for clothing.

By c. 250 BCE, Vani was a sanctuary city with temples, altars, and sacrificial platforms. Its inhabitants moved outside the city walls. Hellenistic bronze statues and sculptures adorned the city, attesting to the impact of Greek culture. Especially noteworthy is a fragmentary bronze torso found in the destruction level of the mid-1st century CE and magnificent bronze lamps adorned with elephant heads, Erotes, and Zeus and Ganymede.

The recently renovated Vani Archaeological Museum-Reserve showcases more than 4,000 objects excavated in Vani since 1985, including silver drinking vessels, bronze and iron figurines used in religious rituals, and elaborately crafted gold jewellery.

Uplistsikhe Cave Town

Uplistsikhe (meaning the castle of the Uplos, son of Mtskhetos, an epic hero in Georgian mythology) is an ancient fortified cave city in eastern Georgia rising high above the left bank of Mtkvari River (known in Greek and Latin sources as the Cyrus River). Uplistsikhe is one of the oldest urban sites in the Caucasus, with evidence suggesting continuous habitation from the first millennium BCE. It features a complex of caves, temples, and tunnels carved into the rock during classical antiquity. The town flourished as a major religious, political, and commercial centre during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, and it was a crucial hub along trade routes (the Silk Road ran along the hills to the north).

The Uplistsikhe complex had a lower, middle, and upper section covering approximately 40,000 cm² (43.0 ft²), with rock-cut structures and temples dedicated to a sun goddess. It had a defensive wall, ditch, passes, tunnels, streets, and a complex irrigation system. Uplistsikhe housed 20,000 people at its peak.

Uplistsikhe became a significant Christian site in the early medieval era, witnessing the construction of a basilica and other Christian structures. The city thrived until the late Middle Ages, after which it declined in importance due to shifting political landscapes and Mongol raids in the 14th century.

Only a small portion of Uplistsikhe can be visited today, but the site is still impressive. It was buried for centuries and only excavated by archaeologists in the 1950s.

Armaziskhevi Archaeological Site (Mtskheta)

Armaziskhevi ("Armazi's Castle") is associated with the ancient town of Armazi, located 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) southwest of Mtskheta, where the Aragvi and Mtkvari rivers meet. It was a significant settlement in the early history of Georgia. Three major cultural layers have been identified, with the earliest dating back to the 4th-3rd century BCE. Armaziskhevi is linked to the worship of Armazi, the chief deity of the Iberian pantheon.

Armazi was the capital of Iberia and the site of Iberian kings' royal residences and tombs. In the 5th century, Vakhtang I of Iberia (r. c. 447/49 to 502/22 CE) moved the capital to Tbilisi. Armazi experienced various cultural influences, including Greek and Roman, and played a role in the complex geopolitical landscape of the region.

Excavations revealed buildings of Hellenistic and Roman times, including the ruins of a citadel, a palace, a six-apse pagan temple, a wine cellar complete with qvevris, and a five-room bathhouse in the Roman style. Various artefacts providing insights into the region's ancient history have been unearthed, including pottery fragments, jewellery, sculptures, and silver dishes from royal family burials, most notably two phiale bearing the busts of Antinous and Marcus Aurelius in their central medallions.

Pompey captured Armazi in 65 BCE during his campaign in Iberia and Colchis. The Roman army built a bridge over the Kura River. It was restored and expanded during the reign of King Vakhtang I, and defensive towers were added on both sides of the bridge. The bridge was used until the middle of the 20th century but is now under water due to the construction of the hydroelectric power station and a rise in the river level.

Gonio Fortress (Apsarus)

The Gonio Fortress, located 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) south of Batumi near the Turkish border, was the largest Roman fort along the Colchian littoral (the Pontus Limes). The site was called Apsarus in ancient times and was connected with the myth of Medea and her younger brother Absyrtus, who was involved in Jason's escape with the golden fleece from Colchis.

The fort was established c. 77 CE to ensure control of the routes running north along the Black Sea and inland to Iberia. It was a 4.75-hectare (11.7 acres) rectangular fort with four gates, 22 towers, and solid ramparts measuring more than 900 metres (3,000 ft) in circumference. The fort experienced several stages of construction and repair up to the Ottoman period.

Excavations have uncovered various buildings, including the principia (headquarters building), praetorium (commanding officer's residence), and barrack blocks equipped with an underfloor heating system, two thermal baths, and water supply systems, all from the Roman or early Byzantine period. Apsarus was a densely populated city. Procopius of Caesarea, a historian of the 6th century, mentions a theatre, a hippodrome, and other facilities usually found in a large city.

Arrian (86 to c. 160 CE), the governor of Cappadocia who reported officially to Roman emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE), inspected the fort in the early 130s during his extensive tour of the Black Sea. He recorded five cohorts in his Periplus of the Euxine Sea, approximately 1,200-1,500 men, who guaranteed safe navigation along the coast, protected traffic from pirates, and kept watch over the coastal tribes.

An interesting museum displays artefacts found at the site. A rich hoard of goldsmithery, known as the "Gonio Treasure," was unearthed in 1974 on the outskirts of the fortress and can be seen in the Batumi Archaeological Museum.

Dzalisa Archaeological Site

Dzalisa is an archaeological site dating back to the ancient kingdom of Iberia. It is situated in the Mukhrani valley, on both banks of the River Narekvavi, some 20 kilometres (12 mi) northwest of Mtskheta, and features remnants of a fortified city. The site can be identified with Zalissa, which was mentioned by Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 to c. 170 CE) as one of the principal towns of Iberia. This archaeological settlement bears witness to the urban development of Iberia in the first centuries CE. It is estimated that the town covered 70 hectares (172 acres).

A significant settlement existed there from the 2nd century BCE and flourished during the Principate before being destroyed in the 4th century CE and later re-settled. Archaeological excavations uncovered the remains of a large architectural complex (the largest discovered in Georgia) with a swimming pool and a bathhouse, part of a villa with mosaic flooring, soldiers' barracks, a water supply system, and burial grounds. The villa has a 48.6 m² (523 ft²) 4th-century floor mosaic depicting Dionysus and Ariadne (identified by Greek inscriptions) in a banquet scene in what was probably a private bathing suite. Their usual entourage surrounds them: Pan, a Satyr, and a Maenad. A Greek inscription is above the mosaic's centre: "Preiskos made this." On both sides of the inscription, two female figures wear long garments and hold musical instruments.

Archaeopolis

Archaeopolis, also known as Nokalakevi and Tsikhegoji ("Fortress of Kuji") to The Georgian Chronicles, was a Byzantine fortified settlement on the Colchian plain's northern edge and Lazica's capital. It consisted of a lower town on the Tekhuri River bank and an upper citadel surrounded by three parallel defensive walls and towers. The city-fortress is a unique example of Georgian urban and fortification architecture in late antiquity. A tunnel leading down to the river was an important part of the fortification and water supply system.

Archaeopolis was pivotal in the Byzantine-Persian wars in the 6th century because it guarded Lazica from a Persian attack. Thanks to its impressive defensive system and garrison of 3,000 men, Archaeopolis withstood Sassanian assaults.

Excavations in the lower town revealed substantial stone buildings from the 4th to the 6th century, including six churches, two bathhouses, and two royal palaces. Beneath these Byzantine layers is evidence of several earlier phases of occupation and abandonment through the 1st millennium BCE.

Petra Justiniana

Petra Justiniana is a massively fortified Byzantine fortress built on a rocky outcrop (the Greek name "Petra" means rock) overlooking the Black Sea. As the name suggests, it was constructed on the order of Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) in 535. Petra was the main trading hub of the province owing to its strategic location at the crossroads of the route linking Lazica with Persia and Armenia.

Petra also became a battleground between the Byzantines and the Sassanian Empire during the 6th-century Lazic War. The fortress was captured in 541 by the Sassanian army under Kosrau I (r. 531-579), who sent his troops through a secretly constructed tunnel and destroyed the towers, forcing a surrender.

The site contains the ruins of a citadel with double walls, an Early Byzantine basilica, two bathhouses, cisterns, and a Middle Byzantine single-nave church.