The Roman army constructed both temporary and permanent forts and fortified military camps (castrum) across the frontiers of the empire's borders and within territories which required a permanent military presence to prevent indigenous uprisings. Although given basic defensive features, forts were never designed to withstand a sustained enemy attack but rather to provide a protected place for accommodation and storage facilities for food, weapons, horses, and administrative records. Over the centuries Roman forts took on a remarkably standardised layout, and the impressive gates and ruins of some of the larger ones can still be seen across Europe today.

Location

Forts were constructed in particular along the frontiers of the Roman empire such as along sections of the River Danube and River Rhine. These prevented incursions from hostile neighbouring groups. Forts were also built during long sieges such as at Numantia in Spain and Masada in Judaea. The majority of forts, though, were built in the interior of provinces in order to deter rebellions and better control the conquered peoples therein. Britain and Dacia are examples of provinces which required a permanent military presence to maintain Roman control. In such hostile territories, forts were linked in a network for mutual support, but there were also isolated forts, especially at naval and supply bases. Roman Britain has remains of over 400 camps, but some of these were either temporary or practice operations for engineers and soldiers to hone their fort-building skills.

Dimensions & Defenses

The earliest known semi-permanent forts were constructed in Spain during the 2nd century BCE, but it was during the reign of Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE) that Roman forts began to assume a standardised form. Forts varied in size with the smallest measuring under a single hectare while the larger ones could be over 50 hectares in area. An example of the larger type fort is at Vetera and Oberaden in Germany, which housed two legions each.

Smaller forts and military camps were more temporary affairs which provided troops with a safe accommodation while on campaign. Small forts were also used by auxiliary units as frontier posts, and small square forts (quadriburgia) with 50-metre-long walls and a single gate were built in all Roman territories during the later empire period. Even larger forts were not self-sufficient for a long period of time and so were usually located near to cities or, alternatively, settlements (canabae) sprang up around the fort to meet its needs and take advantage of the Roman soldiers there who were some of the select few to receive a regular income in the Roman world. Many of these settlements would evolve into medieval towns in their own right.

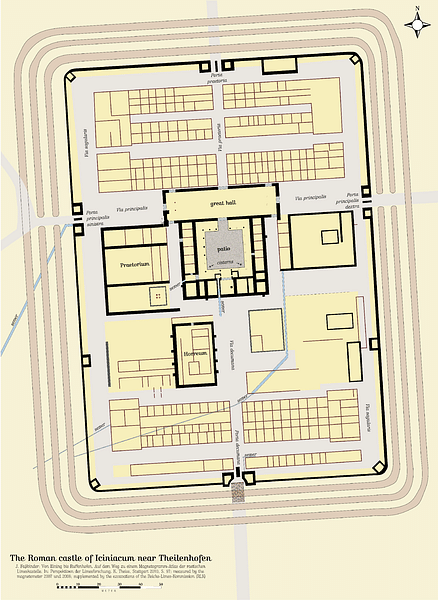

While all forts had their own individual features, there were many elements common to most. Standard forts were typically rectangular with rounded corners, and the walls of most were built using timber and, later, stone set above an earth rampart. Around the perimeter was a double row of ditches (clavicula), the earth from which was used to form the sloping rampart. The walls had three principal gates and towers set at intervals. From the 3rd century CE, when the use of artillery weapons became more widespread, towers projected outwards from the walls to increase the angle of fire.

Gates had two arched entrances which could be closed using wooden doors which were perhaps protected from fire by metal plating. They were locked by a cross bar on the inside, had their own two- or three-storey towers, and were protected by a separate line of ditches projecting out from the walls. Despite these defensive precautions the Romans did not design camps to resist sustained attack as in medieval castles, but rather, they aimed to provide enough measures to act as a deterrent for improvised enemy attacks. No doubt, if a fort was attacked by a large force, then the troops would be mobilised to meet the enemy in the field, but the reality was that for most of Rome's existence its enemies were not capable of the organisation and skills required for successful siege warfare (the Sassanian empire being a notable exception). In the later empire, however, the threat from marauding bands became much greater and forts evolved accordingly with fewer gates, curved towers to protect the gateways, and fan-shaped towers projecting from corners to maximise the field of fire from within and allow the walls and gates better protection. The Saxon Shore forts of Britain display these design features as well as having purpose-built tower battlements to allow the use of catapults.

A temporary camp was built each night when an army was on the march, or for a few days in order to rest and make repairs and resupply, to prepare for a battle, during a siege, or for winter quarters (hiberna). A camp probably took a few hours to build and sometimes had to be done under enemy fire. A wooden palisade protected by a ditch was built, again, on a rectangular plan, with tents instead of buildings but still keeping the general layout described below. Ten men from each century were tasked with building the camp, supervised by a military surveyor (gromaticus) who selected suitable terrain on high ground near a water source. Soldiers sometimes piled up stones against their leather tents for better protection from the elements, a habit useful for archaeologists to reconstruct temporary Roman camps. A single tent would have housed eight men.

Interior Layout

Inside the walls of permanent forts there were a number of separate buildings, which included barracks for legionaries (eight men to a room) and cavalry (men and their horses shared rooms), accommodation for the commanding officer, his family and slaves (praetorium), and sometimes also living quarters for tribunes, granaries (horrea) which were built on raised platforms to better protect their contents from damp, workshops (fabricae), a hospital (valetudinarium), a cistern, and in the case of larger forts, a number of shops (tabernae) or a market (macellum) and Roman baths. The latter were very often built outside the earlier mostly wooden forts as the furnaces needed to provide the underground heating were a real fire hazard. A wide avenue ran around all of these internal structures so that they were safe from enemy missiles landing over the wall.

The fort complex was dominated by the headquarters building or principia, positioned in the dead centre of the fort. Inside the principia was a basilica with aisles and a tribunal set on a raised platform at one end from where the camp commander would lead assemblies, conduct disciplinary hearings, and perform his local judicial duties. There were also rooms for officer recreation (scholae) and for use as offices, the aedes - a shrine where the legion or unit's standards were kept, long rooms used as armouries (armamentaria), and an open courtyard. Under the aedes was the strongroom dug into the floor where the fort's cash reserves were kept.

Forts had two internal streets leading to the three principal gates, so forming a T-shape. These were called the via praetoria (which led from the main gate or porta praetoria) and via principalis, and the principia was located where the two streets met. Gates on the left and right side of the fort were known as the porta principalis sinistra and porta principalis dextra respectively. The rear gate was known as the porta decumana which was connected by a road leading directly to the principia or commander's tent in the case of camps. A good example of a Roman fort built on this standardised plan is the late 2nd century CE Wallsend fort (Segedunum) on Hadrian's Wall which housed 480 legionaries and 120 cavalry.