Masada (“fortress” in Hebrew) is a mountain complex in Israel in the Judean desert that overlooks the Dead Sea. It is famous for the last stand of the Zealots (and Sicarii) in the Jewish Revolt against Rome (66-73 CE). Masada is a UNESCO world heritage site and one of the most popular tourist destinations in Israel.

The last occupation at Masada was a Byzantine monastery, and then the site was largely forgotten due to its remoteness and harsh environment (especially in the summer months). The site was superficially explored in 1838 CE by the American archaeologists Edward Robinson and Eli Smith. Then, between 1963 and 1965 CE, Yigael Yadin, who was both an Israeli military commander as well as an archaeologist, organized the first major excavations with volunteers from around the world.

The source for the history of Masada is Flavius Josephus (36-100 CE), who wrote about the origins of the fortress under the Hasmoneans and the renovations of the site under Herod the Great (37-4 BCE). As an eyewitness to the events of the Jewish revolt against Rome (66-73 CE), he wrote The Jewish War with the last chapter relating events at Masada in 73-74 CE. Josephus described the decision to commit mass suicide at the fortress (960 men, women, and children). However, because he was not an eyewitness to the events, modern debate continues in relation to the historical basis of his story.

Description

This area of the Judean desert is full of hills and wadis (from the winter rains) with numerous caves pocketing the area. The fortress sits on a high mesa-like structure, flat on top, and surrounded by steep ravines on all sides. In antiquity, the only access to the top was a snake-like path on the Dead Sea side of the structure, making it an almost perfect, defensible fortification. The yearly rains helped to fill huge cisterns that were used for both storing water and grain and other foodstuffs. Josephus claimed that one of the Hasmonean rulers, Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BCE), fortified the plateau (although no remains are evident today from this period). After Herod became a client-ruler under Rome, he renovated the area with barracks, an armory, two palaces, Roman baths, a synagogue, and a casement wall surrounding the structure (37-31 BCE). Aware of his unpopularity among some of the Jews, Herod may have selected the site as a possible retreat in case of rebellion.

The Herodian Dynasty

In 63 BCE, the Roman general Pompey the Great (106-48 BCE) captured Jerusalem as part of his campaigns in the East to establish client-kings in the expanding provinces of Rome. He had help from an Idumean chieftain, Antipater, and his son, Herod (and thus the beginning of the Herodian Dynasty, 55 BCE - 93 CE). After the death of Herod, the area was divided into tetrarchies, four regions under his sons. Judea (the Roman name for the southern kingdom of Judah) was ruled by Herod's son Archelaus (23 BCE - 18 CE).

The rule of Archelaus was ineffective and ultimately disastrous, where riots broke out several times at the pilgrimage festivals in Jerusalem. His rule culminated in a tax revolt where 2000 Jews died by crucifixion. Archelaus had to answer to Rome for the unrest and he was banished to exile in Gaul. The Jews then petitioned Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) not to appoint any other Herodians over them. Augustus made Jerusalem and Judea a senatorial province, which meant that proconsuls, procurators, and the legions of the governor of Syria would be responsible for the area.

Many factors eventually contributed to the Jewish Revolt against Rome, not the least of which was that, beginning in 6 CE, the rulers sent from Rome were largely corrupt and ineffectual. Several Jewish leaders in this period were acclaimed to be “the Messiah” (“anointed one”) by their followers. When the mobs became too large or riots ensued, Rome would send in a swat team to take out the leader and as many followers that they could round up. One of the more famous of the Roman rulers was Pontius Pilate (26-36 CE) who figures so prominently in the trial and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth in the gospels.

The Jewish Revolt

The Great Revolt began in the year 66 CE, after several protests against taxes and attacks on Roman citizens. The governor at the time, Gessius Florus, then plundered the Temple in retaliation. The revolt was organized by a sect of Jews known as Zealots, who promoted the idea that only God should rule over them and idealized the period of the Maccabean Revolt (167 BCE) when the Jews were able to abolish Greek rule. Within the group of the Zealots was a faction known as Sicarii (“dagger men”) who were more extreme in that in addition to killing Romans, they also killed any Jews who collaborated with Rome. Several factions of Jews set up a provisional government in Jerusalem. Josephus was given the command of organized resistance in the Galilee.

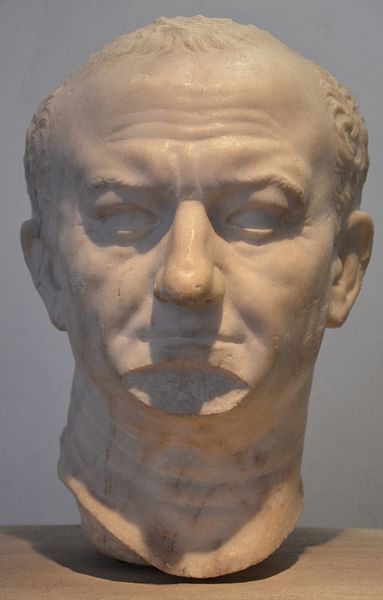

The emperor Nero assigned Vespasian and his son Titus to put down the rebellion. In 67 CE, Vespasian invaded the Galilee and proceeded to conquer most of the rebel strongholds. Josephus was captured at the stronghold of Jotapata. Pending his execution, Josephus predicted that Vespasian would be the next emperor of Rome. Vespasian held off the execution, and eventually Josephus became friends with Titus and reversed his loyalty, claiming that God was now on the side of Rome.

The Siege of Masada

Rome spent the next few years eliminating Jewish rebels in various towns and cities in the region. In 73 CE, Lucius Flavius Silva was assigned the Legion X Fretensis to take the last hold-out of the rebels at Masada. He built siege camps and a circumvallation wall around the plateau to eliminate any chances of escape. Utilizing a natural spur of bedrock, he built a ramp on the western side using Jewish prisoners of war. The ramp facilitated the job of sending a battering ram to the top which finally breached the walls of the fortress in April. The remains of the Roman camps and the circumvallation wall are visible today, as well as portions of the ramp.

It is at this point that Josephus tells the story of the mass suicide. He narrates the speeches of the leader, Eleazar ben Ya'ir, on the theme of freedom and how it was better to die than to be a slave of Rome. Allegedly, their store of food and supplies was carried into the open so that Rome could see that they could have outlived the siege. By casting lots, several of the men were assigned the job of killing the other men, women, and children, laying out their bodies for the Romans to see, and then killing themselves. According to Josephus, only an old woman and a few children who hid in a cave survived to tell the story.

Josephus & Archaeology

Ever since Yadin's excavations, scholars and archaeologists have continually debated the historicity of Josephus' story. Josephus only writes of one palace; archaeology reveals two. His description of the

northern palace contains several inaccuracies, and he gives exaggerated figures for the height of the walls and towers. Unlike the siege of Jerusalem, Josephus was not an eyewitness to the events at Masada. It is improbable that the old woman and the children could remember the detailed speeches of Eleazar. Earlier, in his description of one of the battles in the Galilee, Josephus related a smaller mass suicide at Gamla where he included speeches that are similar to Eleazar's speeches. These speeches incorporate Greco-Roman concepts of the “noble death” in addition to Jewish polemics against slavery under Rome.

In relation to other details, one should note that Josephus spent the rest of his life in Rome where he had access to Roman archives and perhaps reports by field commanders. However, Josephus's writings are not wholly historical works; they are very often understood to be apologies (explanations) to Rome on the history of the Jews as well as Jewish customs. At the same time, his story of the staunch defense at Masada could also be a way in which to flatter Rome; Rome would not deserve praise for conquering a weak, defenseless enemy. And the story would also serve as good propaganda to deter future rebellions by other subjects of Rome.

A major discrepancy involves the problem of the dead bodies. Josephus claimed that the Romans found 960 people, but only 28 bodies have been found so far. A few skeletons were found in the remains of the northern palace, in the bathhouse, while the rest, men, women, and children were found in a cave at the southern tip of the promontory. So where are the rest? An element of Roman punishment for rebels was the concept of “eternal punishment.” Rebels were denied proper funeral rituals so that they could never cross the river Styx and remain in a liminal state between life and death. The Roman army at Masada would not have bothered to bury the dead; cremation would be the solution. However, no levels of ashes for that many have been found at the site. On the other hand, the Romans could have simply thrown the bodies over the side into the ravines below, but again, no remains have been found there.

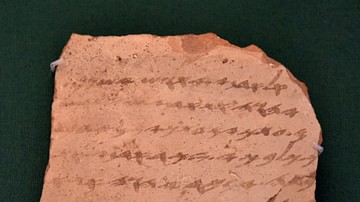

Yadin's excavations uncovered several ostraca, or shard fragments with names, including the name of Eleazar ben Ya'ir. He claimed that these were the “lots” used to determine the leaders of the mass suicide. However, other scholars have claimed that the ostraca could also have been part of a system of ration chits, in the distribution of food. There have been several more excavation seasons at Masada, but the crucial question of the story remains controversial. In the latest excavation and book on Masada (Masada: From Jewish Revolt to Modern Myth, Princeton University Press, 2019), the renowned archaeologist Jodi Magness adds the details of what life was like for Jews under the Romans, as well as the specific pros and cons of the debate. Her ultimate decision is that without further evidence, the story of the mass suicide cannot be verified one way or the other. The question of what really happened at Masada is not one “that archaeology is equipped to answer.”

The Ideology of Masada

In the 1930s CE, the Israeli archaeologist Shmarahu Gutman began taking Israeli youth on trips to Masada. After World War II (1939-1945 CE) and the revelations of the Holocaust, Masada became symbolic of the Zionist ideology that criticized European Jewry for not fighting back during the Nazi “final solution” programs. The battle cry of “freedom,” allegedly promoted at Masada, as well as a romanticized concept of heroism and nationalism, all contributed to the elevation of Masada in contemporary Israel. Many of the special forces units of the Israeli army and air force have participated in a ceremony at Masada. Pre-dawn climbs of the snake-path bring them to the top where their oaths to the armed forces are taken, with the rallying cry “Masada will never fall again!” It is also possible to arrange to have the ritual of either a bar-mitzvah (boys) or a bat-mitzvah (girls), the adolescent rite that conveys adulthood in Judaism, done at the ancient synagogue at Masada.

Some Israelis as well as non-Israelis utilize the metaphor of Masada in their criticism of Israeli nationhood and politics, usually described as a “Masada complex.” This can either refer to an extreme, patriotic zeal for the nation (willing to die for it) or a reference to some Israeli policies that appear “suicidal” as they apply to international relations in the Middle East. In both cases, it refers to the problem of “all or nothing” espoused by some political parties in Israel or relations with the Palestinians.