Pontius Pilate was the fifth magistrate to serve in the Roman province of Judea, created in 6 CE by Roman emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE). His term of office was during the subsequent reign of Tiberius from 26-36 CE. He became famous for the trial and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth (c. 30 CE).

Pilate's Life

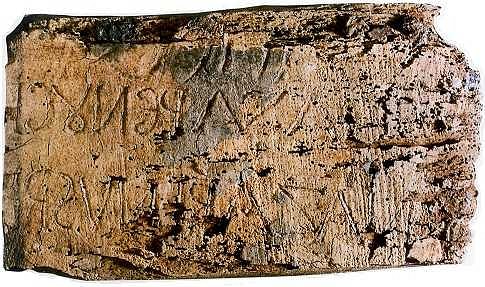

We know very little of Pilate's background, but there is speculation that his name, Pontius, derived from the family name Pontii in Rome, of Plebeian descent. As a historical figure, we have evidence of contemporary literature, coins minted in his name, and an inscription from the base of what may have included his statue from the city of Caesarea. Our literary sources for Pilate include the Jewish philosopher, Philo of Alexandria (c. 20-50 CE), the accounts in the four gospels, and the Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus (36-100 CE).

Philo was part of a delegation sent to Caligula (r. 37-41 CE) when tensions arose in Alexandria between the Alexandrians and the Jewish community. Before he was assassinated, Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) had granted the Jews permission to follow their ancestral customs and their religion and were therefore excused from participation in the Roman and imperial cults. The Alexandrians were attempting to make the Jews conform. Philo described Pilate as "a man of inflexible, stubborn, and cruel disposition" (On the Embassy to Gaius, 299-305). When Pontius Pilate took office, he permitted the legions of Judea to set up portable shields which had inscriptions to honor the emperor. Some Jews saw this as a violation of their ban on images, appeared before Pilate in the amphitheater in the city of Caesarea, threatened to revolt, and were willing to die in protest against the offense. Josephus related the same story, referring to the signa of the shields.

As a Roman magistrate, Pilate was duty-bound to maintain law and order in the province. Philo reported that Jewish officials sent a letter to Tiberius and Tiberius quickly wrote back, "reproaching and rebuking him a thousand times for his newfangled audacity and telling him to remove the shields at once and have them taken from the capital to the city of Caesarea ... to be dedicated in the Temple of Augustus. In this way both the honor of the Emperor and the traditional policy regarding Jerusalem were alike preserved" (ibid). Pilate backed down and removed the images.

Philo and Josephus both reported that Pilate took money from the Temple treasury to build an aqueduct 50 miles long. When the crowds reacted in protest,

[Pilate] made the soldiers mix with the mob, wearing civilian clothing over their armor, and with orders not to draw their swords but to use clubs on the obstreperous. He now gave the signal from the tribunal and the Jews were cudgeled, so that many died from the blows, and many as they fled were trampled to death by their friends. The fate of those who perished horrified the crowd into silence. (Josephus, The Jewish War 2:175-177)

For the writings of both Philo and Josephus, however, it is important to place this material in the historical context of events in the 1st century CE. Between the decades of the 20s to the 60s CE, Jewish-Gentile relations were deteriorating in some cities. A series of corrupt magistrates contributed to the eventual Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE against Rome, led by a group known as the Zealots. Both writers depict Judaism in its most positive light by blaming any problems on corrupt magistrates.

Pontius Pilate in the Gospels

Our earliest gospel, Mark, set the template for the portrait of Pontius Pilate. Written in the context of the Jewish Revolt, Mark was challenged by two problems that affected the emerging movement of the followers of Jesus: Jesus had died by crucifixion, a punishment that was reserved for treason against Rome, and the followers of Jesus had to survive in the Roman Empire. Mark constructed his story by claiming that the Jews sought the death of Jesus from the beginning of the ministry and carried out a false trial against him. He presented a portrait of Pilate as a weak-willed magistrate who was pressured by the Jews to condemn him, even though Pilate could find nothing wrong with him. Having a Roman magistrate declare Jesus innocent (in relation to the punishment for treason), implied that the followers of Jesus were also innocent of any treason against Rome. Mark had to distinguish his Jewish group from those in the recent rebellion.

Matthew's gospel added more details:

While Pilate was sitting on the judge's seat, his wife sent him this message: "Don't have anything to do with that innocent man, for I have suffered a great deal today in a dream because of him." (Matthew 27:19).

In later Christian tradition, she was given the name Claudia Procula and became venerated as a saint in several Eastern Orthodox traditions.

Matthew is also responsible for the famous scene of Pilate washing his hands, which became a metaphor for avoiding responsibility.

When Pilate saw that he was getting nowhere, but that instead an uproar was starting, he took water and washed his hands in front of the crowd. "I am innocent of this man's blood," he said. "It is your responsibility!" (Matthew 27:24).

In Luke's gospel, the writer added another charge against Jesus:

Then the whole assembly rose and led him off to Pilate. And they began to accuse him, saying, "We have found this man subverting our nation. He opposes payment of taxes to Caesar and claims to be Messiah, a king." (Luke 23:1-2).

But earlier, Luke related the story of how spies attempted to trap Jesus:

"Is it right for us to pay taxes to Caesar or not?" He saw through their duplicity and said to them, "Show me a denarius. Whose image and inscription are on it?" "Caesar's," they replied. He said to them, "Then give back to Caesar what is Caesar's, and to God what is God's." (Luke 20:20-25)

In other words, Luke claimed that the leaders had deliberately lied and constructed false charges.

When Pilate heard that Jesus was a Galilean, he sent him to Herod Antipas, the client-ruler for Rome in Galilee. Jesus refused to show him any sign (miracle), so Herod's soldiers "ridiculed and mocked him. Dressing him in an elegant robe, they sent him back to Pilate. That day Herod and Pilate became friends—before this they had been enemies" (Luke 23:11). For the writer of the third gospel, this was most likely an element of the fulfillment of Scripture, as a reference to Psalm 2:

Why do the nations conspire and the peoples plot in vain? The kings of the earth rise up and the rulers band together against the Lord and against his anointed, saying, "Let us break their chains and throw off their shackles." The One enthroned in heaven laughs; the Lord scoffs at them. He rebukes them in his anger and terrifies them in his wrath, saying, "I have installed my king on Zion, my holy mountain." I will proclaim the Lord's decree: He said to me, "You are my son; today I have become your father'" (1-9).

In the Gospel of John, a more credible reason was presented for the condemnation by the Jews. Only found in the fourth gospel, the story of the raising of Lazarus from the dead motivated the crowds in Jerusalem to proclaim Jesus as the messiah. The high priest, determined not to give Rome any excuse to intervene, declared: "You do not realize that it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish" (John, 11:50)

So Pilate came out to them and asked, "What charges are you bringing against this man?" "If he were not a criminal," they replied, "we would not have handed him over to you." Pilate said, "Take him yourselves and judge him by your own law." "But we have no right to execute anyone," they objected. (John 18:29-31)

Scholars continue to debate whether Jews had the authority to execute anyone without Rome's permission. Josephus reported many messianic contenders in the 1st century CE, but they were all killed by Rome, not Jews.

Pilate then went back inside the palace, summoned Jesus and asked him, "Are you the king of the Jews?" "Is that your own idea," Jesus asked, "or did others talk to you about me?" "Am I a Jew?" Pilate replied. "Your own people and chief priests handed you over to me. What is it you have done?" Jesus said, "My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight to prevent my arrest by the Jewish leaders. But now my kingdom is from another place." "You are a king, then!" said Pilate. Jesus answered, "You say that I am a king. In fact, the reason I was born and came into the world is to testify to the truth. Everyone on the side of truth listens to me." "What is truth?" retorted Pilate. With this he went out again to the Jews gathered there and said, "I find no basis for a charge against him. But it is your custom for me to release to you one prisoner at the time of the Passover. Do you want me to release 'the king of the Jews'?" (John 18:33-38)

The discussion of kingship is related to the gospel descriptions of the scourging and mocking of Jesus by the soldiers:

Then Pilate took Jesus and had him flogged. The soldiers twisted together a crown of thorns and put it on his head. They clothed him in a purple robe and went up to him again and again, saying, "Hail, king of the Jews!" And they slapped him in the face. (John 19:1-5).

Scourging was part of the punishment that ended in crucifixion. Only kings and Roman emperors were permitted to wear purple. Pilate brought him out to the crowd, with what became another famous phrase, "Behold the man!" (Ecce homo!; John 19:5)

The 'kingship' conversation also aligns with the Roman method of a public statement, usually attached to a cross, of why the victim was condemned. John reported that the plaque on the cross was issued by Pilate as "Jesus of Nazareth, the king of the Jews" in three languages, Hebrew, Latin, and Greek (John 19:19). The Latin Iesus Nazarenus, rex Iudaeorum became initialized to INRI. This was a reference to Jesus' claim of kingship and thus treason; there was no other kingdom but Rome.

The End of Pilate's Reign

Pilate's reign in Judea ended when he violently suppressed a group of Samaritans who had gathered on Mount Gerizim in Northern Israel, assuming they were insurrectionists. The governor of Syria, Lucius Vitellius, who was officially Pilate's superior, sent him to Tiberius in Rome to answer charges of ineffectual governance in the region. Philo reported that he was also charged with not granting Roman citizens a trial. When he arrived in Italy, Tiberius was dead, and we have no information after this time.

The last historical mention of Pilate was by the Roman historian Tacitus (56-120 CE), who related the outbreak of a disastrous fire in Rome in 64 CE under Emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE). Nero had plans to build what became his Golden House in an area that contained some of the more populous (and poorer) sections of Rome. After the fire wiped out these areas, rumors arose that Nero himself had started the fire. Consequently, to get rid of the report, "Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus" (Annals, c. 116, 15.44).

The Acts of Pilate

By the 2nd century CE, various manuscripts were collected as the Acts of Pilate. Some were rewritten based on earlier manuscripts, such as The Gospel of Peter. This gospel related what happened on Easter Sunday morning, in that the guards posted by Pilate were the first witnesses to the resurrection. Sending for Pilate (and Herod Antipas), Pilate then became promoted as a witness to this miracle. The text exonerated Pilate by placing the blame on Herod Antipas who forced him to do it.

The Acts of Pilate included the claim that Pilate had actually sent a detailed report of the crucifixion to Tiberius and the Roman Senate. The 2nd-century CE Church Fathers, Justin Martyr, and Bishop Tertullian both claimed to have read it. In the Acts, there was a purported letter from Tiberius to Pilate, condemning him for the crucifixion of Jesus. Tiberius tried to convince the Roman Senate to make Jesus a god, but they refused. Tiberius then had Pilate executed for his crime. Right before he was beheaded, a voice from Heaven proclaimed him 'blessed,' and that he will reunite with Jesus at the Second Coming. Eastern Christian communities were generally more positive, claiming that both Pilate and his wife became Christians, and in some versions died a martyr's death. The Western texts retained a more villainous role, claiming that Pilate committed suicide because he realized too late that Jesus was the son of God.

In the Book of the Cock from late antiquity (preserved in Ethiopic and translated into Arabic), Pilate and his wife became Christians after Jesus cured their daughters of their deafness. Pilate was forced to execute Jesus by the Jews, but Jesus forgave Pilate for this action. In a more negative version, the Mors Pilati (c. 6th century) claimed that Pilate was forced to commit suicide, and his body was thrown in the Tiber, where it was surrounded by demons and storms. According to this legend, the body was then removed and thrown into Lake Lucerne in Switzerland.

Both the later medieval apocryphal Gospel of Joseph of Arimathea and the Gospel of Nicodemus included their conversations with Pilate. In the gospel version, these two men were members of the Sanhedrin and secret admirers of Jesus. Under the Roman penal system, convicted traitors were denied proper funeral rituals. The bodies were left on the crosses and then thrown in a ditch. As a rich man, Joseph approached Pilate for the body (with a hint of a bribe). Joseph and Nicodemus provided the funeral trappings for the women.

In 325 CE, Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) organized the First Council of Nicaea, which accepted the Nicene Creed, or a list of beliefs for all (orthodox) Christians. The phrase, "died under Pontius Pilate" was added to validate the historical events in the suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus.

Pilate in Art

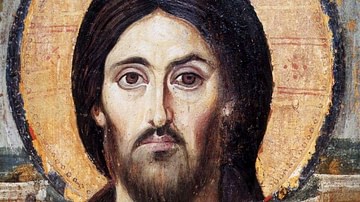

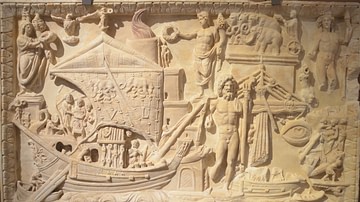

One of the earliest depictions of Pilate is on a Christian sarcophagus from 330 CE. Most of the depictions show him as representing Rome, seated on the curule chair. The 'washing the hands' scene also became popular. By the 11th century, in the Western tradition, depictions of Pilate with Jewish features were adopted, and sometimes with the Devil nearby, influencing him.

A wooden plaque known as the Titulus Crucis is kept in the Church of Holy Cross (Santa Croce) in Rome and was allegedly part of the relics that Constantine's mother, Helena of Constantinople, discovered in Jerusalem on her pilgrimage of 324 CE.

Scala Sancta (Holy Stairs) is a chapel across the street from the Lateran Palace in Rome. Catholic tradition claims that Helena found, and then brought the staircase where Pilate judged and condemned Jesus. Consisting of 28 marble steps, pilgrims must ascend the staircase on their knees.

Helena is also credited with establishing the Via Dolorosa ("the way of suffering") in the Old City of Jerusalem, which highlights specific details of the trials and suffering of Jesus. It begins with what was believed to be the praetorium of the governor, the official quarters or residence, most likely attached to the Antonia Fortress. The next sites are the Church of the Flagellation, the Church of the Imposition of the Cross, and the Church of Ecce Homo. Processions end at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Franciscan Catholic Churches began replicating the events in the 17th century through a ritual that became The Stations of the Cross during Lent and on Good Friday. Each of the stations is represented in art, where the participant simultaneously recites the rosary.

Medieval passion plays reenacted the trials and crucifixion of Jesus, where Pilate often became the most central character. More lines and pathos were added to the role of Pilate's wife, and conversations between the high priests, Annas and Caiaphas, were inserted. In the positive versions, Pilate tried to argue with the high priests to take back the thirty pieces of silver that Judas had received for betraying Jesus after his remorse, but they refused. In negative versions, Pilate humiliated Judas by refusing to make him a servant in his household and then brow-beat him to commit suicide.

Pontius Pilate has a remained a central character in Hollywood versions of the gospel story. Hollywood actors present him as either sympathetic or evil, depending upon the screenplay and the director's version.