The Coronation of Napoleon I as Emperor of the French took place on Sunday 2 December 1804, in the Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral. A sacred ceremony held to legitimize Napoleon's reign, the coronation signaled the birth of the First French Empire (1804-1814; 1815) and established the imperial Bonaparte Dynasty.

Significantly, the coronation was done in the presence of Pope Pius VII (served 1800-1823); along with the Concordat of 1801, this marked the reconciliation between France and the Catholic Church. But the coronation also had a secular component, acknowledging the idea that Napoleon ruled with the consent of the people, who had approved of his elevation to emperor in a plebiscite. The ceremony was unique from the coronations of previous French monarchs, as Napoleon combined various rites from the Carolingian Dynasty, the Ancien Régime, and the First French Republic to add to his legitimacy.

Background: The Fall of a Kingdom

In the two centuries that preceded the French Revolution (1789-1799), absolute monarchy took root in the Kingdom of France. Whereas the authority of early French kings was largely confined to their personal domains around the Île-de-France because of the competing interests of powerful local lords, by the 17th century, power in France had become centralized; indeed, the sun king Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) retained such a tight grip over his realm that he was able to boast "L'état, c'est moi!" ("I am the state"). After crushing a rebellion of feudal lords known as the Fronde (1648-1653), Louis XIV attacked and dismantled the remaining obstacles to his absolute authority, while his various wars, reforms, and building projects helped France become a foremost power in Europe. The sun king ruled from his famously opulent palace of Versailles, where the rigid protocol of court life meant that everything revolved around the king himself. The relative isolation of Versailles from Paris also lent the monarchy an almost mythical air.

Such an extravagant method of governance could not last forever, and the reign of the sun king's successor, King Louis XV of France (r. 1715-1774), saw the kingdom fall further into debt as it became embroiled in perpetual wars. The popular ideas of the Age of Enlightenment alerted many Frenchmen to the grim realities of rampant social inequality behind the Ancien Régime's mask of gilded splendor; tensions continued to simmer before finally boiling over in 1789, the start of the French Revolution. Events such as the Storming of the Bastille and the Women's March on Versailles marked the rapid dismantlement of the nearly thousand-year-old French monarchy, as citizens who had long paid the price of absolutism took their revenge. The final nail in the coffin came on 10 August 1792, when thousands of Parisians stormed the Tuileries Palace and butchered some 600 Swiss Guards. The royal family was imprisoned, and a little over a month later, the monarchy was officially abolished in favor of a French Republic. The hapless former king, Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) was tried for treason and executed on 21 January 1793; his wife, the hated Queen Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), followed him to the guillotine nine months later. The First French Republic had been baptized in royal blood.

Of course, the end of absolutism in France did not mean that it was smooth sailing from there. Eager to prevent the Revolution from spreading beyond French borders, the Ancien Régimes of Europe formed an anti-French coalition, embroiling the continent in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). Initial French defeats caused the rise of the Jacobin-led Committee of Public Safety, which was itself dominated by Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794). Obsessed with creating a perfectly pure and virtuous republic, Robespierre oversaw the arrests and executions of royalists and other suspected political dissidents; his ten-month Reign of Terror ended only with his own downfall and execution in July 1794. Afterwards, the corrupt and ineffective French Directory came to power. Although the French armies were consistently victorious during the Directory's rule, the Directory itself was unpopular. Starvation and poverty were rampant throughout the nation, while various attempted coups spoke to the terminal instability of the government. With the Revolution approaching its tenth year, the population was war-weary and tired of the chaos and was willing to accept any government that could offer them stability.

Such stability was finally offered to them by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), a popular Corsican-born general who seized power in the Coup of 18 Brumaire on 9-10 November 1799. As First Consul of the new government, Bonaparte implemented a new constitution and announced an end to the Revolution. He legitimized his new regime by decisively beating the Austrians at the Battle of Marengo (14 June 1800) and securing an end to the Revolutionary Wars two years later. Despite claiming to be the personification of the Revolution, Bonaparte began taking clear steps toward authoritarianism and began to revive some of the mechanics of the Ancien Régime; he invited counter-revolutionary émigrés back to France, reconciled France with the Catholic Church with the Concordat of 1801, and even reinstituted a system of social hierarchy that was theoretically based on merit but in reality favored the nobility. In 1802, a plebiscite confirmed Bonaparte as First Consul for life, effectively solidifying him as a dictator.

The Transition to Empire

Bonaparte may have had the power of an absolutist king, but he still only held the title of First Consul of a regicidal republic; he knew that in order to both secure his position in France and to be treated as an equal by the monarchs of Europe, he had to establish some kind of hereditary monarchy of his own. An opportunity arose in February 1804, when a royalist conspiracy against his life was uncovered. The Cadoudal Affair, named after its leading participant Georges Cadoudal, was a British-backed plot to kill or kidnap Bonaparte and restore the exiled House of Bourbon to the French throne. After apprehending Cadoudal and the other conspirators, Bonaparte told the French people that he was the protector of the liberties they had won in the Revolution; if he were killed, there would be nothing to prevent France from falling back into political chaos or, even worse, into the hands of the Bourbons. The only solution, he argued, was the establishment of a hereditary monarchy to ensure a seamless transition of power.

In late March 1804, the Conseil d'État met to discuss the best title for Bonaparte to take. Almost immediately the title of 'king' was ruled out to avoid any association with the old Bourbon monarchy. The titles of 'prince' and 'consul' were also dismissed since they sounded too modest. In the end, the Conseil settled on the title of 'emperor' which was, in their estimation, "the only [title] worthy of him and of France" (Roberts, 342). On 18 May 1804, the Senate officially bestowed the imperial title on Bonaparte, who took the regnal name of Napoleon I. Only eleven years after the trial and execution of Louis XVI, France was once again a hereditary monarchy. Napoleon's popularity, and his promises to safeguard French liberties, meant that few people objected; indeed, a plebiscite held to confirm the transition to empire voted overwhelmingly in favor of the measure (with an unbelievable 99.93% approval rating, the plebiscite was certainly doctored, although the Napoleonic regime was genuinely popular).

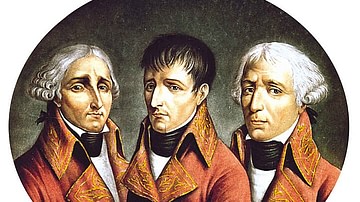

Of France's former republican leaders, most who would have been popular enough to oppose Napoleon's coronation were, by 1804, either dead or disgraced. Those who were still influential enough to rival Napoleon were duly won over with titles. The day after he was proclaimed emperor, Napoleon appointed four honorary and 14 active 'marshals of the empire'; these included loyal followers and family members like Louis-Alexandre Berthier and Joachim Murat, but also potential rivals like Jean-Baptiste Jourdan and Jean Bernadotte who were placated into not making a fuss. By summer, things looked stable enough for Napoleon to begin to plan his coronation.

Preparations

On 12 June 1804, the old Conseil d'État, newly rebranded as the Imperial Council, met at Saint-Cloud to work out the details surrounding the upcoming coronation. The Council decided against holding the coronation at the traditional location of Reims, again to avoid any unpleasant association with the Bourbons. Aix-la-Chapelle was considered for its association with Charlemagne, but it was eventually decided to hold the ceremony in the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, and a date was set for 2 December 1804.

Next, the conversation turned to the heraldry for the new empire. The fleur-de-lys, symbol of the old Kingdom of France, was discarded in favor of an eagle with spread wings, on the basis that the eagle "affirms imperial dignity and recalls Charlemagne" (Roberts, 348). For his personal emblem, Napoleon chose the bee; bees were associated with the early medieval Frankish king Childeric I (r. c. 458-481), an early member of the Merovingian Dynasty. By choosing bees for his emblem, Napoleon meant to link his own dynasty with the Merovingians, often considered as the founders of France. But in order to even have a dynasty at all, Napoleon first needed an heir; by 1804, he was still childless, and it seemed increasingly likely that his wife, the beautiful but aging Joséphine de Beauharnais, would never bear any more children. For now, Napoleon named his older brother, Joseph, as his heir with one of his younger brothers, Louis, second in line.

With these details sorted out, the imperial court could now turn its attention to preparing the cathedral itself. The job was entrusted to the architects Percier and Fontaine, who divided the space into two distinct centers; at one end, near the cathedral chancel, a space was prepared for the religious aspect of the ceremony. Here, the papal throne was installed to the left of the altar, and room was made for the cardinals, archbishops, and other attendant clergy members. In the middle, a prie-dieu was set up so the emperor and empress could kneel before the pope. At the opposite end of the church, near the great nave, a second space was prepared for the secular part of the ceremony. Here, a grand imperial throne was built beneath a triumphal arc decorated with eagles and draped in red velvet. This part of the cathedral was decked out with ancient Greek and Roman imagery, so that an observer would subliminally connect Napoleon with ancient heroes like Alexander the Great. Between the secular and religious areas was enough space for the 6,000 invited guests.

On 2 November, Pope Pius VII left Rome for Paris, and met Napoleon at the end of the month between Nemours and Fontainebleau. Napoleon was hardly an ideal Catholic; indeed, he had flirted with the idea of converting to Islam during his Egyptian campaign and had already made war on the Papal States and imprisoned Pius VII's predecessor. Yet the emperor recognized the importance of religion in such a ceremony and was aware that many of his new subjects favored reconciliation with the Church. The pope, for his part, was at first reluctant to officiate the coronation, but after much negotiation he was eventually persuaded to do so. One of his conditions was that the marriage of Napoleon and Joséphine had to be redone according to the rites of the Church; their wedding in 1796 had been a hasty state ceremony. Napoleon obliged, and his half-uncle, Cardinal Joseph Fesch, performed the religious nuptials on the night of 1 December. Satisfied, Pope Pius VII entered Paris side by side with the new French emperor.

The Ceremony

Guests began to arrive at the cathedral at 6 a.m. on Sunday, 2 December 1804. As they waited for the ceremony to begin, they huddled beneath a neo-Gothic wooden awning to get out of the snow that was beginning to fall around them. An hour later, the first sounds of music were heard as 460 musicians and choristers began to play, belonging to such groups as the imperial chapel, the Feydeau Theatre, and the Opéra. When the doors opened, the guests began to file inside, handing their invitations to one of 92 ticket collectors, as soldiers escorted them to their seats. Along with important French figures, the guests included most of the diplomatic corps with the notable exceptions of representatives from the United Kingdom (which was currently at war with France), and from Russia and Sweden (who were protesting the recent execution of the Duke of Enghien by the French). The pope arrived on foot, beneath a canopy carried by twelve grooms in red damask.

At 10 a.m., the firing of artillery salvoes alerted the city that Napoleon and Joséphine had left the Tuileries Palace and were on their way to the cathedral. The emperor and empress themselves rode in a grand carriage drawn by eight white horses and were accompanied by a procession so large that it had to stop at several points to figure out a way through particularly narrow points. The procession was led by the newly minted Marshal Murat, as governor of Paris, and included Napoleon's family and advisors all decorated with new titles; Joseph Bonaparte as Grand Elector, Cambacérès as Arch Chancellor, and Talleyrand as Arch Chamberlain, among others. At 11 a.m., the procession stopped outside Notre-Dame and Napoleon emerged from his carriage and donned his coronation robe; this was a crimson velvet mantle, lined with ermine and scattered with golden bees. As Joseph helped him put on the robe, which apparently weighed 36 kilograms (80 lbs), Napoleon turned to his brother and said, in their native Italian, "If only papa could see us now" (Bell, 63). Empress Joséphine wore a similar robe that was carried by Napoleon's three sisters.

At 11:45, the emperor and empress entered the cathedral as the choir sang hymns. They were greeted by the Archbishop of Paris who sprinkled them with holy water before they moved to their designated places. According to Laure d'Abrantes, a lady-in-waiting standing close to Napoleon, the emperor soon became weary from the length of the celebration and several times had to suppress a yawn. Yet Napoleon "did everything he was required to do with propriety" (Roberts, 355). At the climax of the event, Napoleon's crown was brought out. Since the traditional French crown had been destroyed during the Revolution, this was a new one, made to resemble the crown of Charlemagne. Napoleon took it and placed it on his own head; though later accounts claimed that this was a spontaneous decision done to spite the pope, Napoleon's self-coronation had actually been rehearsed along with everything else and was done with Pius' approval. Next, Napoleon crowned Joséphine, who knelt before him, a moment immortalized in the painting by Jacques-Louis David.

After the crowning, Pope Pius VII blessed both the emperor and the empress, after which Napoleon gave his coronation oath:

I swear to maintain the integrity of the territory of the Republic: to respect and to cause to be respected the laws of the Concordat [of 1801] and of freedom of worship, of political and civil liberty…to raise no taxes except by virtue of the law; to maintain the institution of the Legion of Honor; to govern only in view of the interest, the wellbeing, and the glory of the French people. (Roberts, 355)

The oath was followed by fresh artillery salvoes and cries of "Long live the emperor!" The imperial procession then left the cathedral and travelled back down the streets of Paris, followed by the papal procession. Thousands of soldiers lined the streets to hold back the throngs of people who hoped to get a glimpse of their new emperor.

Conclusion

Ruling from his glorious palace of Versailles, King Louis XIV had once declared that he was the state, an expression of the absoluteness of his power. Now, a century later, Emperor Napoleon I could certainly make a similar claim. The France he ruled was more powerful, more centralized than the sun king's Ancien Régime, and seemingly had the blessing of both God and the people. Eleven years after Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette lost their heads on the Place de la Revolution, the head of Napoleon was anointed and crowned, ushering in the period of the First French Empire, and delivering the regicidal First French Republic to its grave.

It would not be long before the new emperor would be put to the test; on 11 April 1805, a new anti-French alliance would be launched against him in the War of the Third Coalition (1805-1806). On 2 December 1805, exactly one year after his coronation, Napoleon would defeat the Austrian and Russian armies at the Battle of Austerlitz. Often considered the greatest victory of Napoleon's career, Austerlitz solidified his imperial power that had been proclaimed a year earlier.