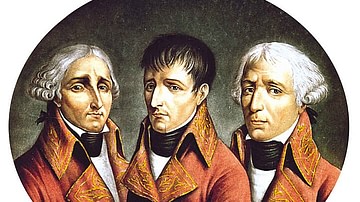

The Cadoudal Affair, or the Pichegru Conspiracy, was a failed royalist attempt to kill or kidnap Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), then the First Consul of the French Republic, and restore the House of Bourbon to the French throne. The conspiracy's discovery led to the controversial execution of the Duke of Enghien and helped facilitate the establishment of the First French Empire.

The British-backed plot began in August 1803, when Chouan leader Georges Cadoudal landed in Normandy along with a group of royalist conspirators. Over the coming months, additional conspirators arrived in France, including General Jean-Charles Pichegru, but before the royalists could put their plan into action, the plot was uncovered, and the conspirators were arrested. Hoping to set an example for other would-be assassins, Bonaparte abducted the Duke of Enghien, a member of the royal Bourbon dynasty, from his estate in sovereign Baden. Enghien was subjected to a sham trial and shot; the execution sent shockwaves throughout Europe, stained Bonaparte's reputation, and served as a catalyst for the War of the Third Coalition (1805-1806). The plot against his life also convinced Bonaparte to hurry up with his plans to establish a hereditary empire; he was proclaimed Emperor of the French on 2 May 1804, and the coronation of Napoleon I took place seven months later.

To Kill a Consul

Early on the morning of 23 August 1803, a lone British frigate approached the rocky cliffs of Normandy, near the commune of Biville. Cloaked in the predawn darkness, the frigate quietly dropped a small group of eight men at the foot of the cliffs before slipping back across the English Channel. The men were French royalist émigrés, committed enemies of the French Revolution who sought the return of the royal House of Bourbon to the throne. Among them was Georges Cadoudal, a tall and burly Breton who had been leading royalist rebels, nicknamed Chouans, for the last decade. Cadoudal and his companions returned to France to complete a daring mission: they meant to kill or kidnap the First Consul of the French Republic, an upstart Corsican general named Napoleon Bonaparte.

Bonaparte had initially seized power in the Coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799. To consolidate his new government, called the French Consulate, Bonaparte enacted policies meant to heal some of the divisions left over from the Revolution. He invited counter-revolutionary émigrés to return to France and reclaim their status as citizens, cracked down on countryside brigandage, and even pardoned Chouans who laid down their arms. During his tenure as First Consul, Bonaparte also restored some of the trappings of the Ancien Régime to strengthen France's position in the eyes of Europe; a new social hierarchy was implemented, power became more centralized, and France was reconciled with the Catholic Church with the Concordat of 1801.

Despite these apparent reconciliatory policies, any naïve royalists who assumed Bonaparte was sympathetic to their plight soon realized they were mistaken. On 5 March 1800, a tentative meeting between Bonaparte and Cadoudal at the Tuileries Palace turned stormy, causing the Chouan leader to flee the country. That same year, the self-styled King Louis XVIII of France wrote to Bonaparte from exile, offering him his choice of ministerial postitions in exchange for the French throne. The First Consul took more than six months to respond before flatly refusing the king's request, urging instead that Louis "sacrifice your interest to the peace and happiness of France" (Roberts, 249). Indeed, Bonaparte had no need for the royalists' support; on 14 June 1800, he defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Marengo, and two years later, he secured an end to the decade-long French Revolutionary Wars. These achievements greatly boosted the popularity and legitimacy of the new regime, allowing Bonaparte to extend his term in office from ten years to life. He was now, essentially, a dictator.

This move toward authoritarianism did not go unnoticed; many pro-republican Jacobins, especially prominent in the army, were disturbed by this apparent betrayal of the Revolution. Bonaparte had made enemies from across the political spectrum as noticed by Anne-Jean-Marie-René Savary, commander of the gendarmes of the Consular Guard, who reported groups of "envious, mischief-making, and for the most part narrow-minded men" who were "busy in stirring up the people" against the Consulate (Mikaberidze, 188). One such group would strike on Christmas Eve 1800; on the route that Bonaparte was taking to the opera, a so-called 'infernal machine', a carriage filled with gunpowder, exploded, killing eight and wounding 26. Though Bonaparte himself was unhurt, this marked the first major attempt on his life.

While the assassination attempt had likely been carried out by royalists, Bonaparte chose to blame the Jacobins, who he viewed as a greater political threat, and 130 Jacobins were subsequently rounded up and deported. But he did not leave the royalists unpunished; a column of soldiers led by General Jean Bernadotte swept through Brittany, mopping up latent Chouan resistance. Among the Chouans who were killed was Colonel Julien Cadoudal, Georges' brother. Georges Cadoudal himself was forced to flee to England during this time; he now nursed a personal grudge against Bonaparte.

The Conspiracy

During his exile in London, Cadoudal formulated a daring plot to assassinate the First Consul and restore the Bourbon monarchy. He recruited Jean-Charles Pichegru, a fellow royalist and disgraced French general who had been exiled during the Coup of 18 Fructidor in 1797. Pichegru's task was to take control of the army once Bonaparte had been neutralized; to gain a better chance of winning military support, Pichegru was also tasked with convincing General Jean Victor Moreau to join the plot. Moreau was the second most popular general in France after Bonaparte himself. Though he was an ardent republican, Moreau had become disillusioned with Bonaparte's rule and could feasibly be persuaded to join.

The conspirators were also aided by the British government. In May 1803, after a brief period of peace, France and the United Kingdom were once again at war; since Bonaparte was busy planning an invasion of England itself, it was in Britain's best interests to neutralize who they saw as a rogue dictator. Letters between members of British naval surveillance and government ministers suggest that the British funded the conspiracy; at the very least, they ferried the conspirators across the Channel. In the months after Cadoudal landed in Normandy in August 1803, other small groups of royalists were dropped off in the same area, with Pichegru landing on 16 January 1804. After arrival, the conspirators were to get into position and wait for the signal to strike. Unfortunately for them, they were not nearly as clandestine as they believed.

The Plot Unravels

Joseph Fouché, minister of police for the French Republic, was a cunning and crafty man. Even during the tumultuous revolutionary years, he had never been on the losing side of a coup, a testament to his vast network of spies. Indeed, his agents had infiltrated anti-Bonapartist circles in Paris, and Fouché even had eyes and ears in London. As soon as Cadoudal landed below the cliffs of Biville, Fouché knew about it. Keeping watch in Normandy, his men captured a royalist named Danouville shortly after he landed; Danouville's decision to hang himself in his cell rather than submit to questioning alerted Fouché that the royalists were planning something big.

In September 1803, a letter written by one of Cadoudal's companions, Dr. Querelle, was intercepted by Fouché's agents. The letter, which Querelle had unwisely sent to his brother-in-law in Vannes, confirmed Cadoudal's involvement and revealed Querelle's own location. Querelle was arrested in October; when threatened with the guillotine, he revealed the names of the main conspirators including Cadoudal, Pichegru, and Moreau, and gave up the locations of several safehouses in Paris where the plotters might be hiding. Fouché's men searched the safehouses in February 1804 and arrested two additional conspirators by the names of Louis Picot and Bouvet de Lozier. Subjected to torture, the two men broke down and revealed the details of the plot. According to them, the conspiracy was to have been triggered by the arrival of a Bourbon prince on French soil, though they claimed not to know the identity of the prince.

Meanwhile, on 28 January 1804, Pichegru met with General Moreau at his home in France. Moreau seems to have considered joining the plot but ultimately decided against it once it was revealed that Cadoudal was involved; as much as he hated Bonaparte, Moreau had no desire to see a Bourbon Restoration. Still, he fatefully promised Pichegru he would not go to the authorities, thereby becoming complicit. Around the same time, Fouché finally had enough information to approach Bonaparte with an outline of the plot. When Fouché told him of Moreau's alleged involvement, the First Consul was genuinely surprised, exclaiming, "What! Moreau in such a plot!" (Roberts, 334). Bonaparte responded first by bolstering security in Paris. The number of gendarmes patrolling the streets was increased, and the men were told to be on the lookout for Cadoudal. Homes of known royalists were searched, the jury system was suspended, and the passwords to the Tuileries Palace and Malmaison were changed.

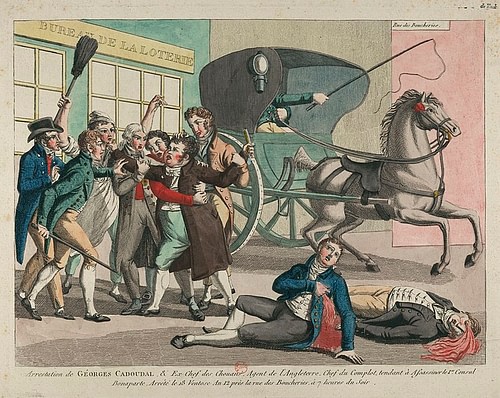

With the capital secured, Bonaparte came for the conspirators. At 8 a.m. on 15 February, Moreau was arrested and sent to the Temple prison in Paris. His close friends, generals Liebert and Souham, were also arrested but were shortly released. Pichegru was found eleven days later, hiding out in a house on the rue Chabanais in Paris; the general managed to fight off three gendarmes with his fists before the brawl was finally ended by "violent pressure on the most tender part of his body, causing him to become unconscious" (Roberts, 335). Cadoudal himself was not arrested until 7 p.m. on 9 March, after a dramatic carriage chase through the streets of Paris. At the climax of the chase, Cadoudal shot and killed a gendarme that jumped onto his carriage and wounded another; it took a swarm of policemen to hold him down and drag him off to prison. With Cadoudal's arrest, the main threat to Bonaparte's life was over.

The Death of d'Enghien

With the apprehension of the main conspirators, one question still remained: who was the Bourbon prince whose arrival in France was to signal the conspiracy to begin? Bonaparte and his ministers initially suspected Comte d'Artois, the younger brother of Louis XVIII who was usually found pulling the strings of similar pro-Bourbon activities (Artois was also the future King Charles X of France). However, when Savary was sent to Normandy to investigate, he found no signs of Artois' involvement. Shortly after Pichegru's arrest, Bonaparte's ministers suggested another candidate: Louis Antoine de Bourbon-Condé, Duke of Enghien.

Described by historian Duff Cooper as "young, handsome, and chivalrous," the 31-year-old Duke of Enghien was a member of the House of Condé, a cadet branch of the Bourbon dynasty. His grandfather had led the French royalist army during the Battle of Valmy in 1792, and Enghien himself had expressed desires to lead an invasion of Alsace and restore the Ancien Régime. Though there was no evidence connecting Enghien to the Cadoudal plot, Bonaparte wanted to set an example by arresting the young duke. However, there was one major problem: Enghien was not in France. Instead, he was living as an émigré in the Electorate of Baden, a sovereign state and part of the Holy Roman Empire.

This did not dissuade Bonaparte, who was encouraged by Fouché and by his foreign minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand to arrest the duke anyway. On the night of 14-15 March, General Michel Ordener and 200 dragoons crossed the border into Baden, arriving at the duke's estate of Ettenheim at 5 a.m. Ordener abducted Enghien and also took the duke's dog, his documents, and the 2.3 million francs in his safe. The documents revealed nothing about the Cadoudal plot but did prove that Enghien had offered to serve in the British army and had accepted money from London. Enghien was taken to the fortress of Vincennes, where he was submitted to questioning. Though he denied having been in contact with Pichegru, Enghien made no attempt to hide his hatred for Bonaparte's government and readily admitted his desire to help the enemies of the French Republic. At 2 a.m. on 21 March, a brief military tribunal found Enghien guilty of treason. The duke was then brought to the castle moat where he was shot and buried in a grave that had already been dug; the question of his guilt had never been in doubt.

Reactions to Enghien's Execution

Many were horrified that the duke had been abducted and killed on such flimsy charges, while Parisians worried that the execution marked the start of a second Reign of Terror. Aristocrats mourned the loss of the last prince of the illustrious House of Condé, while liberals began to second-guess their support of Bonaparte, whose actions more closely resembled an oppressive tyrant than a revolutionary hero.

Even Bonaparte's closest supporters questioned the necessity of the execution; Bonaparte's own wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais, had allegedly begged her husband to spare Enghien's life, while Bonaparte's trusted lieutenant Joachim Murat hesitated in setting up the tribunal. Bonaparte defended his actions, declaring that Enghien had wanted to "sow disorder in France and kill the Revolution in my person; I had to defend and avenge it. I had to show what I was capable of" (Furet, 238). If nothing else, Bonaparte succeeded in this regard; no further royalist plots were made against his life. He had shown the world, in his own words, that his "veins run with blood, not water" (Mikaberidze, 190).

Not every European nation objected to Enghien's death; Prussia and Austria remained silent on the matter, while Spain even voiced its approval. But for certain monarchs, the execution was a step too far. King Gustav IV of Sweden broke off the negotiations of a Franco-Swedish alliance as soon as he heard the news; Gustav would later adopt Enghien's dog, making a collar for it that read "I belong to the unhappy Duc d'Enghien" (Roberts, 339). Tsar Alexander I of Russia was also greatly insulted, less so because of the murder itself and more because Bonaparte had violated the sovereignty of Baden, whose duke was Alexander's father-in-law. This was just the latest in a series of French actions that seemed to challenge Russia's status in Europe and could not be allowed to stand.

The Russian court entered a period of mourning for Enghien and sent letters of protest to Paris and to the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire. This put the German states into somewhat of a bind; while they did not want to risk antagonizing France by agreeing with the tsar's protest, neither could they afford to ignore it and risk offending Russia. In the end, the Duke of Baden announced that Bonaparte had given a satisfactory explanation for the violation of Baden's sovereignty, putting an end to the matter. This did nothing to assuage Russia's fury; in April 1804, Russia began plotting against France and made a secret alliance with Austria. Enghien's execution, therefore, helped plant the seeds of the War of the Third Coalition, which would break out the following year. For this reason, and for the stain on Bonaparte's reputation, Fouché would later remark that the execution was "more than a crime – it was a mistake" (Buttery, 15).

Aftermath

As Europe reacted to Enghien's death, the conspirators of the Cadoudal affair met their fates. On the morning of 6 April, General Pichegru was found dead in his cell, apparently strangled by his own cravat. Though his death was ruled as a suicide, many questioned whether Bonaparte or one of his ministers had something to do with it (it is unlikely that Bonaparte would have given the order himself at a time when he was getting so much flack for Enghien's death). Moreau was tried in June 1804, but the evidence against him was flimsy, and he still enjoyed much public sympathy. Much to Bonaparte's annoyance, Moreau received the lightest possible sentence, two years' imprisonment; this was later revised to exile, and Moreau left for the United States. Of the other alleged conspirators, 21 were acquitted, four were sentenced to prison, and 19 were sentenced to death. Though some of the death sentences were later commuted, 12 conspirators – including Cadoudal – were guillotined in the Place de Grève on 25 June 1804, the only mass guillotining to occur during Bonaparte's reign.

Bonaparte had been toying with the idea of establishing a hereditary empire in France, and the discovery of the Cadoudal conspiracy gave him a golden opportunity to do it. Bonaparte made the argument that he, as the supposed personification of the Revolution, was the only thing standing between France and political turmoil. If he were killed, France would be torn apart by war and the Bourbons would be restored. Bonaparte claimed that a hereditary empire would ensure the stability the French people desired and would protect the gains of the Revolution.

It was a rather weak argument, but Bonaparte was popular enough for that not to matter. On 2 May 1804, the legislative assemblies passed three motions that oxymoronically proclaimed Bonaparte as "emperor of the French Republic"; on the 18th, the Senate officially proclaimed the First French Empire. Therefore, Cadoudal was right when he jokingly remarked from his prison cell, "We have done more than we hoped to do. We meant to give France a king, but we have given her an emperor" (Mikaberidze, 194).