There were many famous women of early Christianity who made significant contributions to the development of the faith but have since been largely forgotten. Some have been canonized by the Church or recognized in other ways, but their efforts were usually eclipsed by their male counterparts. Even so, these women helped set the foundation of the Church.

Women feature prominently in the gospels and Book of Acts of the Christian New Testament as supporters of Jesus' ministry. The most famous of these is Mary Magdalene, most likely an upper-class woman of means, instead of the prostitute label still wrongly attached to her, but there is also Mary and Martha, the sisters of Lazarus, Mary the mother of Jesus, the Woman at the Well in Samaria, the Woman Taken in Adultery, and many others who are referenced warmly at times in the epistles even when women, in general, are given second-class status.

The first people recorded as seeing the resurrected Christ were women, and women are integral to the first Christian community as depicted in the Book of Acts. Jesus himself has nothing to say about the equality of the sexes; he seems throughout the gospels to take it as self-evident that there is nothing inherently superior in either. Saint Paul (l. c. 5 to c. 67), however, and other writers of the epistles which make up the New Testament, introduced the Christian misogyny which linked women with Eve and the Fall of Man.

Eve, as Paul the Apostle writes, was deceived and then tempted Adam to sin; left to his own devices, Paul implies, Adam would have remained happily in the Garden of Eden and so would have all his and Eve's descendants. Women were, therefore, not to be trusted, could not hold authority over men, and should learn from men in silence lest they tempt Adam's descendants further (I Timothy 2:11-14). Even so, Paul himself seems to echo Jesus' own implied view of the equality of the sexes when he writes:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female [in Christianity]: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3:28)

The many other passages from the New Testament, supporting male superiority, were – and still are – quoted far more often than the line from Galatians, and women are still denied leadership positions in a number of Christian denominations and sects. This was not always so, however, and there were many women in the early Church who held positions of authority, established religious orders, and wrote influential theological works prior to their suppression. Women did not find their voice in Christian history again until the Middle Ages (476-1500) and, more so, during the Protestant Reformation.

Women in Early Christianity

Anyone with even a cursory knowledge of Christianity has heard the term "Church Fathers" but far less so "Church Mothers" – and yet, in the early days of Christianity, women were at the forefront of the religion. Roman women were among the first to take Christianity seriously, and there are many stories – preserved in the writings of the Church Fathers themselves and in tales of martyrs – of strong women converting their households to the new faith.

Some of these early Church Mothers embraced Christianity so completely that they gave away whatever they had – often substantial sums of money and large estates – to help the poor, the sick, and the needy in compliance with Jesus' directive that "Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me" (Matthew 25:40). Service to others, especially to those in need, was service to Christ himself.

A number of these women came to be known as Desert Mothers, founders of monastic orders in the deserts of Egypt, Syria, Persia, and Asia Minor. Known as Ammas (mothers), they were the female counterpart to the better-known Abbas (fathers) such as Saint Anthony the Great (also known as Saint Anthony of Egypt, 251-356), credited with establishing Christian monasticism. Other women were famous writers who blended pre-Christian literature and philosophy with biblical precepts, while still others contributed to building projects, social programs, and evangelical efforts while also supporting men whose contributions today are well known.

Any student of the Bible knows that Saint Jerome (l. 347-420) translated the work from Hebrew and Greek to Latin, creating the Vulgate translation, which would be used by the Church for well over the next 1,000 years; few people, however, know that the idea for that translation came from a woman named Paula who not only inspired the work but proofread and edited it for publication.

Shift in Power

Women's role in the Church remained more or less the same even after Christianity was elevated by Constantine the Great (l. 272-337) in 313 through his Edict of Milan, which proclaimed tolerance for the new faith. After the Council of Nicaea of 325, however, the situation changed. Constantine called the council at his villa at Nicaea to standardize Christian belief and practice. The most important issue was deciding on Christ's status as God, god-man, or prophet, but there were many other aspects of Christianity which were far from uniform. There were, in fact, many different versions of the central religious concept of a "One True God" redeeming the world.

While standardizing the Christian vision, Constantine also wanted religious practice to reflect that uniformity. Pope Clement I (l. c. 35-99) decreed that only men could serve as priests or hold authority in the Church because Christ had chosen only males as his apostles. The ecclesiastical writer Eusebius (l. 263-339) records that the council, following Clement's lead (and most likely influenced by Paul's admonitions on female inferiority) decreed women as laypersons who could serve in subordinate positions but could have no authority over men. By the time of the Council of Nicaea, however, many women had already proven themselves capable and inspiring religious leaders and many more would prove so going forward.

Ten Should-Be Famous Early Christian Women

The ten women listed here are chosen from either end of the spectrum: those whose names might be familiar to some and those few or none have ever heard of. These ten are only a very small sample of the many women who contributed to the development of early Christianity, and readers are encouraged to explore the subject more fully through the books listed in the bibliography below. The ten women are:

- Thecla the Apostle

- Perpetua the Martyr

- Amma Syncletica of Alexandria

- Saint Marcella

- Macrina the Younger

- Proba

- Saint Paula

- Melania the Elder

- Eudocia

- Egeria

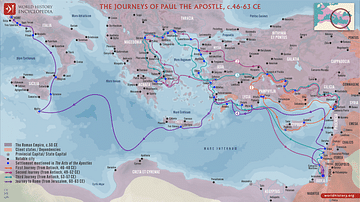

Thecla (l. 1st century) is known from the apocryphal work The Acts of Paul and Thecla which narrates her conversion to Christianity by Saint Paul and her subsequent travels with him, divine rescue from various persecutions and death, and career as a healer, preacher, and inspiring religious leader. Thecla's story has been regularly dismissed in the past as Christian fiction, but modern scholars believe that, though there is no doubt some exaggeration of events, the account is based on an actual woman. In his epistles, Paul regularly mentions women who have helped him, and Thecla's story is not so very different from many others save for the repeated miraculous rescues from death. One aspect of her story known to be true of women of her time is her vow of chastity, which she kept from her conversion to the end of her life. Women choosing a chaste life, even if they were married, was a dramatic statement of individuality in claiming rights over their own bodies and, by extension, over the direction of their lives.

Perpetua (l. 181-203) is famous as an early Christian martyr who, along with her slave Felicitas, refused to renounce her faith and was executed for it. Scholar I. M. Plant notes that "in nearly every case, stories of Christian martyrs are fictional ... the martyrdom of Perpetua, however, is generally taken to be an exception to this rule" (164). A citizen of Carthage, Perpetua was arrested during a local persecution of Christians in c. 202-203 under the reign of Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193-211). She was 22 at the time and nursing her newborn when she was taken to prison. Her father, a pagan in good standing with authorities, begged her to renounce her faith, but she refused and was executed along with Felicitas. Based on details of the original narrative concerning motherhood, scholars believe the account was written by a woman – the early part, perhaps, by Perpetua herself – which, as I. M. Plant points out, would make her story "the earliest extant Christian literature written by a woman" (165).

Amma Syncletica of Alexandria (l. c. 270 to c. 350) is one of the best-known Desert Mothers and an early founder of the monastic tradition. Syncletica was the daughter of wealthy parents in Alexandria, Egypt, whose beauty attracted many suitors. She refused them all, however, due to her devotion to Christ. After her parents' death, she cut her hair, gave her inheritance to the poor, and left the city with her younger sister (who was blind) to live a life of chastity, poverty, and solitude near the crypt of a relative. In solitude, she is said to have wrestled with demons who tried to convince her to resume her previous life of wealth and pleasure, but she remained true to her faith. Having attained the enlightenment and closeness to God she sought, she consented to teach others who sought her out and provided guidelines for this early monastic order of women. These rules, recorded by her biographer (possibly the bishop Athanasius of Alexandria, l. 296-373), would later influence European monasticism.

Saint Marcella (l. 325-410) was a wealthy Roman Christian woman who, after her husband's death, devoted herself to her faith through a life of chastity and service to others. She opened her lavish home on the Aventine Hill of Rome to others seeking a life of self-denial, prayer, fasting, and mortification of the flesh. She was a friend of the future Saint Paula and correspondent with Saint Jerome. Marcella, formerly one of the wealthiest women in the city, gave away or sold her worldly goods, including all her clothes, jewelry, and expensive cosmetics to benefit the poor and to live free of possessions in communion with Christ. Like many early Christian women, Marcella reclaimed her identity through chastity, refusing to remarry even though the law dictated she should, and dedicated herself to her improvised monastic order which would inspire other women to follow her lead. She died in the Visigoth sack of Rome 410 CE.

Macrina the Younger (l. c. 330-379) was a Christian ascetic whose devotion to God inspired the work and life of her far more famous younger brothers, Saint Basil the Great (l. c. 329-379) and Saint Gregory of Nyssa (l. c. 335 to c. 395). Macrina, like many of the others on this list, was born to wealthy parents in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and arranged to marry well. When her fiancé died, she refused to marry anyone else and chose a life of chastity and prayer, claiming (as many other mystics did) that Christ was her bridegroom and she needed no other. Macrina practiced a rigid asceticism and devoted herself to the education of others, especially her younger brothers. After her father's death, she and her mother moved to an estate on the River Iris in Pontus where she established a Christian community devoted to perfecting their relationship with God and was frequently consulted by pilgrims who came to seek her counsel.

Proba (l. c. 322-370) holds the distinction as the first female Christian writer solidly attested by documentation. She is known for the genre of literary work called a cento ('patchwork') in which an author used lines from established poetic works, woven with their own, to create a completely new work of art. In the present day, this would be 'sampling' in popular music where an artist borrows a well-known melody, in whole or in part, to inform their original piece. Proba came from a wealthy Roman family and was most likely raised in Roman pagan tradition before converting to Christianity sometime before embarking on her literary career. She combined the poetry of Virgil with biblical themes to emphasize the eternal and heroic aspects of Christianity. Her works were later used in Roman classrooms to teach upper-class children as they subtly combined the pagan history of the past with Christian ideals.

Saint Paula (l. 347-404) was the close associate of Saint Jerome who encouraged him to translate the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Latin, thus creating the Vulgate Translation, which continued in use for the next 1,500 years as the authoritative scripture of Christianity. Paula was another wealthy Roman aristocrat who, after the death of her husband, was drawn to the monastic community of women established by Marcella on the Aventine Hill. She became acquainted with Saint Jerome through Marcella and traveled widely with him, establishing a religious center in Bethlehem and practicing strict asceticism including abstinence. She helped Jerome translate the Bible, proofread his work, and edited it for publication. When she died, her passing was deeply mourned by the Christian community, and she was sainted within a year.

Melania the Elder (l. c. 350-410) was a Desert Mother honored for her devotion to God and support of Christian orders. She was a member of one of the wealthiest families in Roman Hispania who moved with her proconsul husband and family back to Rome only to watch all but one son die of the plague. After losing her family, she converted to Christianity and renounced the world, traveling to Egypt to live in a monastery. Unlike other Christian converts, Melania did not give away her worldly goods and used her substantial wealth to support Christian communities and initiatives. When the monks of her order were exiled to Palestine, she went with them and supported them until they could return. She founded two monastic orders in Jerusalem, which she administrated, and is regarded as a Desert Mother for her strict asceticism and devotion to solitary prayer.

Eudocia (l. c. 400-460) was one of the most prolific writers of her time, who created numerous works on Christian themes which, like Proba's work, drew on pre-Christian literature. She was born in Athens and named Athenais before converting to Christianity around the age of 20 and taking the name Aelia Eudocia following her baptism. Her works were quite popular and ranged from a cento drawing on Homer to poetry about her husband's life and military victories, to saints' lives and church history. She is probably best known for her work The Martyrdom of St. Cyprian, which tells the story of the chaste Christian Justa, the attempts by the pagan sage Cyprian to seduce her, his conversion to Christianity, and martyrdom for his faith.

Egeria (also known as Etheria, l. c. 380s) was a Christian traveler and writer known only from her work Itinerarium (also known as the Itinerarium Egeriae = Travels of Egeria). Based on the text, she was a woman of the upper class who went on pilgrimage to significant sites mentioned in the Bible. She traveled through the regions of modern-day Turkey, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and back to the region of Anatolia. Her work was popular enough to be copied and is recognized in the modern-day as completely unique for its time as it is a deeply personal account of Egeria's travels while also providing insight into the condition of the sites she visited, how one traveled, and – since it was composed in Latin – how that language was written at the time.

Conclusion

The contributions of these women were recognized by their male contemporaries who included accounts of their lives in their works on male saints. Amma Syncletica was so highly regarded she was given her own biography, and Saint Jerome praised Paula in his works. The works of Proba and Eudocia seem to have been widely read, judging from the number of copies, and even though Egeria's work was not discovered until the 19th century, it was recognized then as appearing in excerpt form in other works from shortly after her time.

Why these women were erased from official church history is debated by various scholars with the answer always depending on the political, religious, or gender values of the writer making the claim. In almost every case, the arguments in these debates say far more about the modern-day writer than they do about the subject at hand. Scholar Laura Swan, however, sums up the situation succinctly, writing:

Women's history has often been relegated to the shadow world: felt but not seen. Many of our Church fathers became prominent because of women. Many of these fathers were educated and supported by strong women, and some are even credited with founding movements that were actually begun by the women in their lives. (3)

As the Church developed from its legitimization by Constantine through the Middle Ages, women lost more and more ground in equal rights and basic dignity. The medieval Church encouraged the view of women as dangerous temptresses to be avoided by any pious man, stained by the original sin of duplicitous Eve, and even their association with the Virgin Mary could not fully redeem their nature. The most probable cause for the exclusion of women of great merit from church history is simply that they did not fit the Church's narrative of devout and pious men vs. devious, sinful women and, when faced with the choice of changing that narrative or changing history, the past was modified.