The Wampanoag Confederacy was a coalition of over 30 Algonquian-speaking Native American tribes who lived in the region of modern-day New England, specifically from Rhode Island down through Massachusetts and parts of Connecticut. They are best known in American history as the natives who helped the pilgrims of Plymouth Colony survive in the New World.

The Wampanoag have also been known as the Massasoit (after their most famous leader) Philip’s Indians, Pokanoket, and Wopanaak. Wampanoag translates as “People of the First Light”, “Eastern People” or “People of the Dawn” as they considered themselves the first to see the sun rise. The tribes had lived in the region since c. 12,000-9,000 BCE as nomads until c. 7000 BCE, when permanent settlements and seasonal camps were established, then continuing a semi-nomadic lifestyle afterwards.

At some point prior to c. 1600 CE, one tribal chief had gathered the others under his leadership to form a confederacy. This was most likely in response to the Iroquois Confederacy, founded sometime in the 12th century CE, which had grown powerful by uniting tribes that formerly fought each other. By 1620, the Wampanoag Confederacy was led by Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661) of the Pokanoket tribe who assisted the pilgrims of Plymouth Colony beginning in 1621.

European traders and explorers had been visiting the region of New England since the late 16th century CE and had already greatly reduced the Native American population through the introduction of diseases they had no immunity to by the time the pilgrims arrived in 1620. English colonization of the land, especially between 1630-1660, pushed the tribes further inland, finally resulting in King Philip’s War (1675-1678) between the tribes under Massasoit’s son Metacom (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676) and the colonists.

The English won the war after Metacom was killed in 1676, and the tribes formerly of the Wampanoag Confederacy, as well as others who had remained neutral during the conflict, were dispersed, moved to reservations, sold into slavery, or left the region voluntarily. In the present day, only the Mashpee and Aquinnah tribes remain on their ancestral lands and have only recently been granted official recognition by the US government.

Early History & Confederacy

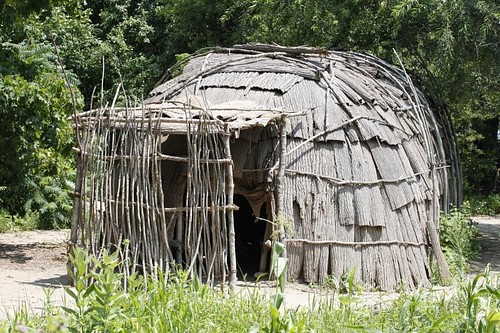

Paleo-Indians began arriving in the region of modern-day New England over 12,000 years ago as hunter-gatherers following big game. Around 7000 BCE, they began harvesting the waters off the coast and established seasonal camps made up of small homes (wetuash, wigwams) with more permanent settlements inland of longhouses. They lived off what they could catch, forage, or find, and began to establish tribal territories to protect their resources. By 2340 BCE, they had a burial culture and religion, social hierarchy (as evidenced by grave goods), presumably some form of government, and long-distance trade.

By 443 BCE, the people had been influenced by the so-called Adena Culture of the Ohio River Valley as evidenced by a change in their burial practices which now mirrored those of the Adena – burying their dead in a fetal position beneath a mound of earth – and were largely sedentary before c. 1000 CE when maize (corn) is thought to have arrived in the region from the south. The development of the bow and arrow (c. 700 CE) which made hunting easier, and agricultural advances in planting maize, beans, and squash (the so-called Three Sisters), led to more permanent settlements and cultural development.

It is unknown when the tribes were formed into a confederacy, but as noted, it is thought to have been after the 12th century CE in response to Iroquois’ aggression following their own unification. Prior to this time, the tribes fought each other for status, resources, or to avenge an insult and retain personal honor; after the formation of the confederacy, united tribes raided the villages of those who were unaffiliated. Wars were conducted as guerilla raids on communities where warriors would strike quickly and retreat. The vanquished would then pay tribute to the victors – if that had been the purpose for the attack – or would be left alone. Wars of conquest were unknown to the Native Americans as they had no concept of land ownership comparable to the European model.

Land Ownership & Spirituality

To the Native American tribes, the earth was a gift, a loan, which could not be owned. The resources of nature which allowed the people to live had not been earned by any human action but had been given freely by the creator god Kiehtan and maintained by his assistant Hobbamock (after whom the famous Pokanoket warrior Hobbamock, d. c. 1643 CE, was named). One tribe could not conquer the land of another because that other tribe did not own it. Tribes formed territories based on their past in that particular area, and these territories were often fluid as the people intermarried or tribes merged. Scholar James Wilson comments on the Native American concept of land rights and territories:

If you try to grasp this picture by looking at a map, it can at first glance seem confusing. There are none of the simple straight lines we expect from political divisions: the names – particularly along the Atlantic seaboard, which bore the brunt of [European] contact – are a wild jumble, all squashed together or tilted at odd angles to fit…To make sense of it, you have to realize that what you are seeing is a snapshot of one moment in a constantly changing situation: these are not nation states, but groups of culturally – and often physically – related peoples who move within frontiers shaped by custom and mutual understanding rather than legal definition. But the impression of chaos – one of the key European perceptions of the eastern Indian – is illusory: although they managed their relationship with the land and with each other in a profoundly different way, their world was at least as orderly as contemporary Europe’s. (47)

Part of the order Wilson references was informed by the tribes’ spiritual beliefs that included the concept of 'present past'. The stories told kept the past alive in the present, but this 'present past' was linked closely with the land on which the events had taken place. The myth of the great giant Moshup, whose enormous feet had made the valleys, waterways, and islands of the region, had no meaning elsewhere. Memory lived and made the past present only as long as those remembering remained where events had taken place.

The spirituality of the tribes of the Wampanoag Confederacy was based on the concept of the Good Spirit Kiehtan who had created the world (though, in some stories, it is the Divine Giant Moshup) and the spirits which inhabit all things. All the earth was alive with these spirits and so, although one might cut down a tree to make a canoe, one thanked the spirit of the tree for its sacrifice. The practice of slash-and-burn agriculture, hunting, fishing, and other means of gaining subsistence followed the same model. As Kiehtan was concerned with celestial matters, and Mother Earth with birth and rebirth of living things, Hobbamock was considered the intermediary between the people and the Creator God as well as a problem-solver when things went wrong between the tribes and Mother Earth. People prayed to Hobbamock primarily, lesser spirits, or their ancestors who passed on their petitions to the higher entity.

Government, Agriculture & Daily Life

In this same way, the Wampanoag government was hierarchical with a Great Chief at the top, surrounded by his powwows (shamans) and counselors, known as pniese, comparable to the European concept of a noble knight. The pniese were both elite warriors and spiritual protectors who guarded the chief against physical and metaphysical threats and provided counsel when asked. Each of the tribes that made up the Wampanoag Confederacy was set up in this same way but was subordinate to the Great Chief (to whom they paid tribute) who, in the early 17th century, was Massasoit. Massasoit was the man’s title (meaning Great Sachem = Great Chief), his given name was Ousamequin. When Massasoit became chief is unknown, but he had already organized the tribes into a confederacy with an economy based on agriculture by the early 17th century.

He would have been chosen by a council of female elders as the Wampanoag, and the other tribes of the confederacy, were matrilineal and matrifocal – meaning one’s bloodline and status was passed down through the woman’s side of the family and women were responsible for making many of the major decisions concerning the life of the tribe, although men usually held the highest positions and were always responsible for warfare.

Women’s duties included planting, tending, and harvesting crops as well as negotiating trade agreements between tribes. The principal crops were corn, beans, and squash which were irrigated by diverting stream beds. Women also built the longhouses of the permanent settlements as well as the temporary shelters of the wetuash (singular, wetu) for the men on hunting expeditions or for seasonal settlements. A wetu was a cone-shaped structure made of saplings covered with bark (often birchbark), and mats woven of reeds. Longhouses were larger, made of saplings bent U-shaped and fastened at both ends to the earth, covered with reed-woven mats and bark, some up to 200 feet long or, in the case of communal structures, even longer. With both types of shelter, a hole in the roof allowed smoke from the fire out and the longhouse had a bark cover over this hole which kept out rain and could be adjusted for wind direction and changes in weather.

Daily – or nightly – activities for women also involved the production of clothing made from animal skins. Moccasins and outerwear such as cloaks were greased with fat for waterproofing. Women also made wampum, beads and shells strung tightly together which told a story and served as a type of currency but could also be – and often were – sacred objects of a tribe. Tobacco was chewed or smoked as part of religious rituals, in sealing contracts, as a stimulant (especially on hunts), and as medicine, but not recreationally. While the women made clothes, the men made tools and weapons including axes, bows, arrows, hammers, knives, spears, tomahawks, and war clubs as well as canoes made of logs which were hollowed through controlled fires and scraping the burnt wood with shells or sharpened rocks.

The day began at dawn, which was observed with prayer and thanksgiving, and ended after dark. Girls were brought up to learn female roles and responsibilities and boys to follow the model of their fathers. Boys were encouraged to play sports, especially a kind of football played with a small leather ball which encouraged dexterity, speed, reaction time, and general good health. From a very young age, boys were also instructed in archery, canoe-making, hunting, and fishing. Entertainment consisted of songs, dance, and, especially, storytelling which kept the myths of the past as well as the deeds of one’s ancestors alive.

Plymouth Colony & the English

By c. 1600, the Wampanoag Confederacy was the most powerful military and political force in the region, periodically engaging in warfare with the Abenaki, Narragansett, Nipmuc, Massachusett, and Pequot tribes as well as others associated with the Iroquois Confederacy. Between c. 1610-1618, however, most of the Pokanoket and almost all of the Patuxet tribe died of diseases brought to the region by European traders. Some modern writers now claim that this 'plague' was actually leptospirosis contracted by the natives from water polluted by animal urine, but this is challenged on the grounds that leptospirosis is not often transmitted person-to-person and is not always fatal in humans. The modern claim seems to be little more than a deflection of blame away from Europeans and toward the natives who actually died, most likely, from smallpox or some similar European illness the natives had no natural immunity to.

When the Mayflower arrived off the coast in November of 1620, Massasoit at first invoked the spirits to get rid of them but by this time he had lost a significant number of people and was no longer as strong as he had been. He was reduced to paying the Narragansett tribute when only ten years before they had been paying him. After the English survived the winter of 1620-1621, it seemed they were going to stay and so, in an effort to restore his power, he decided to make contact with them and form an alliance.

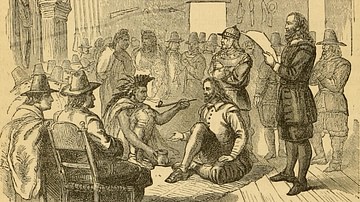

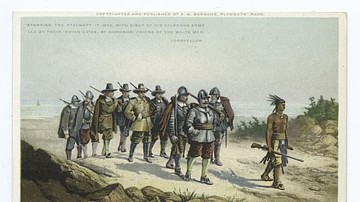

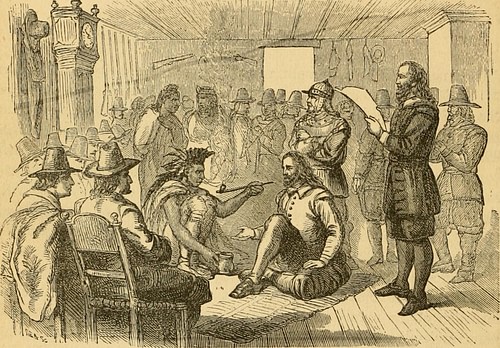

He first sent the Abenaki chief Samoset (l. c. 1590-1653), a prisoner in his village who spoke English, as an emissary, and Samoset, after determining that the colonists were interested in peaceful relations, encouraged further interaction. Massasoit then sent Squanto (also known as Tisquantum, l. c. 1585-1622) to live among the colonists and teach them how to survive. Massasoit and John Carver (l. 1584-1621), the first governor of Plymouth, signed the Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty on 22 March 1621, pledging mutual support, defense, and friendship. The great chief then left Squanto among the colonists and, sometime later, sent his right-hand man, Hobbamock, to keep an eye on Squanto, one of the last survivors of the Patuxet tribe, who, like Samoset, was a prisoner whom Massasoit did not trust.

The Plymouth Colony only survived, and later flourished, through the intervention of Massasoit. The second governor of the colony, William Bradford (l. 1590-1657), continued to honor the treaty and acknowledged the great debt owed to Squanto, Massasoit, and the tribes of the Wampanoag Confederacy. Although it is sometimes claimed that the so-called First Thanksgiving of fall 1621 was the pilgrims’ way of thanking the Native Americans for their help, this is not supported by the primary documents. Neither Bradford nor the other chronicler of Plymouth Colony, Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655) makes this claim, and Winslow, in fact, is clear in his account that Massasoit and his warriors arrived at a feast already in progress uninvited, most likely in response to the sounds of celebratory musket fire they interpreted as a signal for help.

Immigration & Loss of Land

Massasoit’s strategy worked, and the Wampanoag Confederacy again became the dominant power of the region, subjugating the Narragansett and other tribes to their former status. The treaty was mutually beneficial as it established Plymouth Colony as the first successful English settlement in the region. This success, however, encouraged the arrival of more immigrants. Merrymount Colony (1624-1630) was established by Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647) soon after but failed with the arrival of John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649) and his 700 Puritan colonists in 1630 who disapproved of Morton’s behavior and deported him.

Winthrop founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 which was followed by the Providence Colony in 1636, founded by Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683), an exile from Massachusetts Bay Colony who was given refuge by Massasoit and provided with land. Connecticut Colony was founded that same year and New Haven Colony in 1638, both by other exiles from Massachusetts Bay who could not conform to the rigid vision of the Puritan magistrates of Boston.

As more English arrived on the shores of New England, more land was required and the ancestral territories of the tribes of the Wampanoag Confederacy began to shrink. Some lands were acquired in transactions the English believed were fair, but they had a completely different understanding of property ownership than that of the natives. To the indigenous people, the valuables they received were gratuities given in thanks for permission to hunt and farm on Wampanoag land, while to the English, the transactions were permanent transferals of land rights.

Conclusion

The treaty Massasoit and Carver signed in 1621 held throughout the chief’s life, but after his death, relations between the indigenous tribes and the immigrants began to unravel. Massasoit was succeeded by his son Wamsutta (also known by the name Alexander Pokanoket, l. c. 1634-1662) who was accused by the colonists – ironically enough – of unfair land deals and summoned to answer the charge by assistant governor Josiah Winslow (l. c. 1628-1680). Shortly after his visit to the colony, Wamsutta died, and his brother, Metacom (King Philip), claimed he had been poisoned. Metacom launched King Philip’s War in 1675 in an effort to stop the ever-increasing land theft by the colonists but was killed, after being betrayed by one of his own, in 1676 after which the war was won by the colonists.

Even tribes which had remained neutral, such as the Mashpee and Narragansett, were persecuted afterwards, and more land taken in retribution. Of the over 6,000 indigenous people who had inhabited the region in 1620, only around 400 were left. Those that were not sold into slavery or who did not leave the region on their own were moved onto reservations and, as more land was required by the English, even these reservations shrank. In the present day, only the Aquinnah and Mashpee tribes retain ancestral lands and are federally recognized, and this was only granted recently. Many other tribes, whose pasts remain intimately tied to the land of their ancestors, still await just treatment and recognition by the US government which, even if granted, will not return tribal lands to those whose people lived and died on it for thousands of years.