The medieval period of Japan is considered by most historians to stretch from 1185 to 1603 CE. Stand out features of the period include the replacement of the aristocracy by the samurai class as the most powerful social group, the establishment of shogun military rulers and their regents, the decline in power of the emperors and Buddhist monasteries, and a stratification of feudal society into lords and vassals as well as a lasting class differentiation based on profession. The country witnessed long periods of civil wars as warlords and large estate owners (daimyo) fought for prominence and the central government struggled to unify Japan. On the other hand, there were developments in agriculture, commerce, and trade. The arts flourished, especially ink painting and performance arts. Finally, Japan's presence on the international stage became more involved with the Mongol Empire attacking Japan in the late 13th century CE and Japan invading Korea in the late 16th century CE, both campaigns ending in failure. All in all, then, a busy period of development and one which saw the population of Japan rise from around 7 million at the beginning to around 25 million at the end of it.

Medieval Time Periods

The history of medieval Japan is traditionally divided into the following periods:

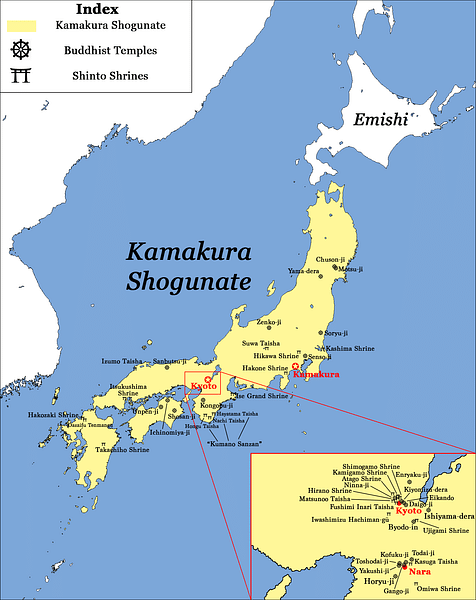

- Kamakura Period (1185-1333 CE)

- Muromachi Period (1333-1573 CE)

- includes the Sengoku Period (1467-1568 CE)

- Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1573-1600 CE)

Alternatively, the period may be divided into the following two shogunates:

- Kamakura Shogunate (1192-1333 CE)

- Ashikaga Shogunate (1338-1573 CE)

Kamakura Period

Shogun: Minamoto no Yoritomo

The Heian Period (794-1185 CE) ends and the Kamakura Period (Kamakura Jidai) begins with Minamoto no Yoritomo's (1147-1199 CE) defeat of the rival Taira clan at the Battle of Dannoura in 1185 CE, the final act of the Genpei War (1180-1185 CE). The period is named after Kamakura, a coastal town southwest of Edo (Tokyo) which was the Minamoto clan's base. Yoritomo established himself as the first shogun (military dictator) of Japan from 1192 CE, thus offering the first alternative to the power of the emperor and imperial court which had ruled Japan since before written records began. Technically, the emperor - then Go-Toba (r. 1183-1198 CE) - was above the shogun, but in practice, it was the reverse as whoever had control of the largest army also controlled the state. The position of Emperor of Japan, still based at Heinakyo (Kyoto) did maintain a ceremonial function, and imperial endorsement was still sought by shoguns to give a veneer of legitimacy to their own rule.

Yoritomo would be shogun until his death in 1199 CE and, after a brief spell as shogun by his eldest son, Yoritomo's wife, Hojo Masako (1157-1225 CE), and her father, Hojo Tokimasa, decided to rule themselves. In doing so they not only promoted the interests of the Hojo clan but also changed Japanese politics forever by creating the position of shogunal regent. In this new arrangement, the regent shogun had the real power, the shogun became a mere puppet and the Hojo dominated all key shogunal government (bafu) posts. The system of the shoguns would last until the Meiji Restoration of 1868 CE.

Feudal Society

With the rise of the warlords, Japanese society was arranged around the feudal relationship between lord and vassal. The former gave lands to the latter in return for military service. In the case of a shogun or lord having many estates, he might give some of them to a steward (jito) - a position open to men and women - to manage and collect the local taxes with that official then entitled to fees and tenure. The role of steward was frequently given as a reward to loyal members of the shogunate. Many jito became powerful in their own right, and their descendants became daimyo or influential feudal landowners, while another layer of landowners was the military governors or constables (shugo) who had policing and administrative responsibilities in their particular province. This system would run right through the medieval period.

Women continued to be used as a tool for social progress in this period via the practice of marrying daughters into families of superior status. This occurred not just among elites but also in rural communities. Women were largely made responsible for the household and its servants if there were any, but there were also some women warriors and small business proprietors. Women could inherit property, had some divorce rights and freedom of movement, but these did vary over time and place. In addition, information regarding women's rights is often lacking in the male-dominated historical record and practical daily life was, in any case, very likely different from official and legal pronouncements on what women could and could not do.

Economically, the country prospered as agricultural techniques improved (e.g. double-cropping, better iron tools, fertilizers and hardier strains of rice were all employed). Trades became more specialised and were governed by guilds, while trade with China boomed with Japanese gold, swords, and timber exchanged for silk, porcelain, and copper coinage amongst other things. In the 15th century CE, Korea would also trade with Japan, exporting cotton and ginseng, in particular. Villages began to grow in size as the road networks improved and small businesses and markets made them more attractive and convenient places to live.

Mongol Invasions & Decline

The success of the Kamakura regime is perhaps best indicated by its ability to withstand its greatest challenge: the Mongol invasions. The Mongol leader Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294 CE) was keen to expand his empire and attacked Japan in 1274 and 1281 CE. Both campaigns ultimately failed thanks to stiff samurai resistance, poor logistics and poorly built ships on the part of the Mongols, and two typhoons. These providential storms were called by the Japanese kamikaze or 'divine winds' because they destroyed the Mongol fleets and saved the country.

The Kamakura government was ultimately weakened by the invasions because of the high cost of keeping a standing army in anticipation of a third attack. The shogunate came to an end when unpaid samurai and ambitious warlords were rallied by Emperor Go-Daigo (r. 1318-1339 CE) who wanted to restore imperial power. This was the so-called Kenmu Restoration, which lasted from 1333 to 1336 CE. Go-Daigo found a willing ally in the traitorous army commander Ashikaga Takauji who attacked Heiankyo while another rebel warlord, Nitta Yoshisada (l. 1301-1337 CE), attacked Kamakura. Takauji wanted to be the new shogun, and he defeated Yoshisada in battle, capturing Heiankyo in 1336 CE. Go-Daigo was exiled, although he then established his own rival court at Yoshino, a situation of 'Dual Courts' which was not resolved until 1392 CE. Takauji appointed Komyo as his puppet emperor (r. 1336-1348 CE), who formally bestowed on his master the coveted title of shogun. Thus, the Ashikaga Shogunate was launched in 1338 CE.

Muromachi Period

Government & Daimyo

This period gets its name from the relocation of the capital to the Muromachi district of Heiankyo. Unlike the relative stability of the preceding period, Japan was now beset with a seemingly endless cycle of civil wars and competition for power between rival warlords, beginning with Ashikaga Takauji fighting his own brother between 1350 and 1352 CE.

The system of government of the Ashikaga Shogunate followed much the same lines as the Kamakura Shogunate and did manage to control most of central Japan. The outer provinces were another matter, though, and these became ripe for the daimyo to rule their area as they wished, making it difficult for the government to extract taxes from them. Some daimyo were efficient and fair administrators, and villages continued to prosper and grow across Japan as farmers sought both security in numbers and the benefits of working together on communal projects such as digging irrigation channels. In the absence of any authority from the central government, villages often governed themselves. Small councils or so were formed which made decisions regarding laws and punishments, organised community festivals, and decided on regulations within the community. Some villages got together to form leagues or ikki for their mutual benefit.

The Onin War & Sengoku Period

Within the Muromachi period was a subperiod of about 100 years, most of it fighting, hence its name of the Warring States or Sengoku period. Things kicked off with the Onin War (1467-1477 CE), a civil war between rival warlords and samurai, which brought hardship, robbery, and brutality to the doorstep of many ordinary people. Japan seemed at war with itself and its rulers bent on destruction. The conflict ended in 1477 CE, but there were only losers and no resolution to the militarism and rivalries that beset the country far into the second half of the 16th century CE. One consequence of the strife was the development of castles and castle towns (jokomachi) as villagers sought the protection of a well-fortified base.

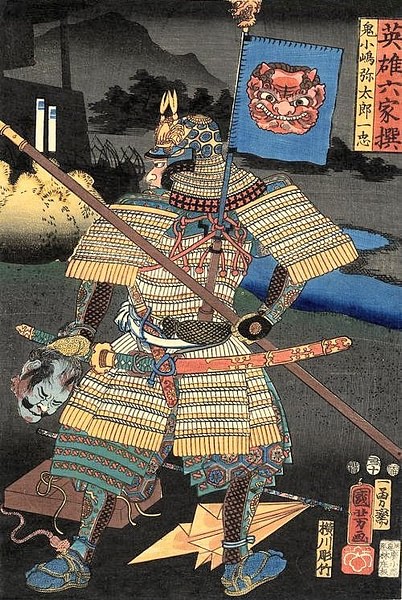

Samurai

As the number of warlords was reduced thanks to the attrition of the wars and those who survived became more powerful, so field armies increased in size. The composition of such armies became more complex, too, not only with samurai but also specialised troops like the lightly armoured infantry or ashigaru. There were cavalry units, too, the ninjas - specialist spies, assassins and saboteurs - and men dedicated solely to procuring and transporting supplies and equipment.

Despite these developments, the samurai (or bushi as they were also known) remained the most important, and certainly most prestigious warrior on and off the medieval battlefield. Their name denotes a social class rather than military occupation, but those who were fighting warriors were typically trained since childhood to ride, swim, and become proficient at the martial arts. Samurai could handle all weapons but were especially proficient at using the bow and sword, and their appearance was distinctive thanks to their shaved front heads and armour made of intricately stitched leather and metal. Making up around 5% of the overall population, samurai developed a code of honour, the bushido, which promoted loyalty, courage, and self-discipline. Samurai were expected to defend their lord's interests and honour, and they even sometimes committed ritual suicide (seppuku) if they failed in this endeavour.

Decline & Oda Nobunaga

The end of the Muromachi period came when one warlord finally dominated all his rivals: Oda Nobunaga (l. 1534-1582 CE). Expanding his territory through the 1550/60s CE from his base at Nagoya Castle, largely thanks to his disciplined army of samurai and innovative use of gunpowder, Nobunaga seized Heiankyo in 1568 CE and then exiled the last Ashikaga shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, in 1573 CE. By the end of that decade, Japan was finally becoming a single unified country.

The Azuchi-Momoyama Period

Oda Nobunaga would rule until his death in 1582 CE. The unification of the country then continued under his successors, the warlords Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598 CE) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616 CE). This period of history is known as the Azuchi-Momoyama Period - Azuchi being the castle on Lake Biwa that Nobunaga used as his HQ and Momoyama ('Peach Mountain') being the castle HQ of Nobunaga's former general Toyotomi Hideyoshi, located in Fushimi, south of Heiankyo.

To increase state revenue, from 1571 CE an extensive land survey was begun to make the tax system more efficient. At the same time, a strategy employed to make the country more law-abiding was to confiscate all weapons held by the peasantry from 1576 CE onwards, the so-called 'sword hunts.' To bring the Buddhist monasteries into line with government policy - they had become rich, powerful, and capable of fielding armies - Nobunaga attacked several, most infamously the Enryakuji monastic complex on the sacred Mt. Hiei near Kyoto in 1571 CE.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Hideyoshi continued Nobunaga's work of unifying Japan, helped by his massive army of 200,000 men and canny diplomatic skills which convinced daimyo to join him. Western Japan, Kyushu, and Shikoku were now brought under the central government's control. Hideyoshi then developed a rigid class system what would become the shi-no-ko-sho system, with four different levels (in order of importance):

- warrior (shi)

- farmer (no)

- artisan (ko),

- merchant (sho)

Each class was given an importance based on its production value, and no movement between the levels was permitted. It would remain the basis of Japanese society into the modern era.

Hideyoshi was not satisfied with just Japan in his grip and wanted to build an empire. To that end, between 1592 and 1598 CE, he invaded Korea with an aim to then move on to Ming Dynasty China (1368-1644 CE). The invasions, also known as the Imjin Wars, ensured the medieval period finished with a bang, but they were failures as the Koreans put up a stiff resistance, especially their navy led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin, and the Ming sent a large army to defend its tribute-giving neighbour. The Japanese army had made impressive inroads and even captured Seoul and Pyongyang at one point, but the death of Hideyoshi in 1598 CE signalled a retreat back to Japan. A power struggle then followed, and after his victory at the Battle of Skeigahara (1600 CE), Tokugawa Ieyasu took the title of shogun in 1603 CE. Thus the Tokugawa Shogunate was established and the post-medieval Edo period (1603-1868 CE) begun.

Religion

Japan continued to mix Buddhism and Shinto with traditional beliefs throughout the medieval period. New forms of Zen Buddhism were introduced from China: the Jodo Sect (Pure Land), founded c. 1175 CE by the priest Honen (1133-1212 CE), and the Jodo Shin Sect (True Pure Land), founded in 1224 CE by Shinran (1173-1263 CE), Honen's pupil. Both sects simplified the religion and stressed that enlightenment and advancement to heaven were open to all regardless of social status. The most important Zen monastery was the Kencho-ji in Kamakura, built in 1253 CE. Zen principles of austerity and restraint became very popular with samurai. Another popular Buddhist sect was Nicheren, founded by the monk of the same name (1222-1282 CE), which stressed the importance of chanting from the Lotus Sutra holy text. Buddhist monasteries were important providers of education to all classes and many hosted schools of artists of all kinds.

In 1543 CE the first European contact was made with Japan when three Portuguese traders were shipwrecked. With the Europeans, and those who followed, came two new ideas: quality firearms and Christianity. The new religion was encouraged by Oda Nobunaga because it challenged the power of the Buddhist monasteries and helped with foreign trade, but Christians were persecuted by his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi, most infamously in the episode of 1597 CE when 26 Christians were crucified in Nagasaki. Christian missionaries were another significant provider of education, setting up general schools wherever they settled.

Art & Architecture

Japan was wholly dominated by its warriors in the medieval period, and this situation was reflected in its austere domestic architecture and interior decor, its art, and literature. The period would produce much martial-themed renga poetry, histories, and war tales (gunki monogatari), the most famous work being The Tale of the Heike (Heike monogatari) which first appeared c. 1218 CE and tells of the struggle to establish the Kamakura Shogunate. Two converted villas in Heiankyo once owned by warlords are the Kinkakuji or 'Temple of the Golden Pavilion' (1397 CE) - so-called because of its shimmering gilded exterior - which was followed by its twin, the Ginkakuji or 'The Serene Temple of the Silver Pavilion', completed in 1483 CE. A third is Ryoanji (1473 CE) in Kyoto, now the most-visited Zen rock garden in Japan.

The minimalism of Zen Buddhism would have a significant influence on calligraphy and ink painting, epitomized by the work of the Zen priest Sesshu (real name Toyo, 1420-1506 CE) who specialised in suiboku - black ink and water on white paper scrolls, in a style that has been described as an austere form of impressionism. Medieval portraiture of such figures as emperors and shoguns, in contrast, became more realistic in the medieval period. Large-scale sculpture is perhaps best seen in the 1252 CE Kotokuin Temple of Kamakura, which has a massive bronze statue of Amida Buddha measuring 11.3 metres (or 37 ft) in height.

By the Azuchi-Momoyama period and the decline of the Buddhist temples, Japanese art and architectural decoration focussed much more on secular subjects, especially birds, flowers, and people doing everyday tasks, and there was much greater use of bold colours in paintings, gilding on buildings, and decorative objects like screens and boxes.

Performance art was one of the lasting products of the medieval period. Noh (Nō) theatre developed from the 14th century CE and derived from older dance and music rituals performed at temples and shrines. In Noh, mask-wearing male actors made highly stylised movements accompanied by music with some brief spoken words to explain the general story which told of gods, demons, and heroes, and their various moral predicaments. The extravagant and richly embroidered costumes of the actors would greatly influence late medieval and early modern fashion in Japan.

Another development was the Japanese Tea Ceremony (chanoyu), which gained a much wider appeal thanks to the combined efforts of the monk Murato Shuko (1422-1502 CE) and the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (r. 1449-1473 CE). This restrained and precise ceremony took place in special rustic teahouses or a sparsely furnished tearoom and was an opportunity for relaxed conversation and to show off a few choice antiques. In this and other pursuits, the medieval period has thus made a lasting contribution to Japanese and, indeed, world culture.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.