The Kamakura Period or Kamakura Jidai (1185-1333 CE) of medieval Japan began when Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-1199 CE) defeated the Taira clan at the Battle of Dannoura in 1185 CE. The period is named after Kamakura, a coastal town 48 kilometres (30 miles) southwest of Tokyo which was used as the Minamoto clan's base. Yoritomo would establish himself as shogun or military dictator of Japan from 1192 CE, thus offering the first alternative to the power of the emperor and imperial court. The Kamakura period saw lasting developments in government, agriculture, and religion and managed to withstand the Mongol invasions of the late 13th century CE. The period came to an end with the fall of the Kamakura Shogunate in 1333 CE when a new clan took over as shoguns of Japan: the Ashikaga.

Minamoto no Yoritomo & the Taira

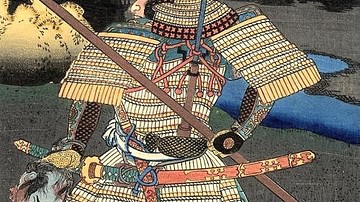

During the preceding Heian period (794-1185 CE), the court of the Japanese emperor was still important and still considered divine but it had become sidelined by powerful bureaucrats who all came from one family: the Fujiwara clan. Towards the end of the period, another two important groups evolved in Japanese politics, the Minamoto (aka Genji) and Taira (aka Heike) clans whose members were often minor relations of the emperors. With their own private armies of samurai, both clans became important instruments in the hands of rival members of the Fujiwara clan's internal power struggle which broke out in the 1156 CE Hogen Disturbance and the 1160 CE Heiji Disturbance. The Taira, led by Taira no Kiyomori, eventually swept away all rivals and dominated the Japanese government for two decades. However, in the Genpei War (1180-1185), the Minamoto returned victorious, and at the war's finale, the Battle of Dannoura, the Taira leader, Tomamori, and the young emperor Antoku committed suicide. The Minamoto clan leader Minamoto no Yoritomo was left the most powerful military leader in Japan.

Minamoto no Yoritomo was the son of Minamoto no Yoshitomo (1123-1160 CE) and the grandson of Minamoto no Tameyoshi (1096-1156 CE), both influential Minamoto clan members with the latter being the head of the clan in the mid-12th century CE. Having defeated all rivals and dispatched his younger brother Minamoto no Noriyori and other key members of his own family, Yoritomo stood alone at the head of the Minamoto clan.

The Kamakura Shogunate

Minamoto no Yoritomo made himself the first shogun, in effect military dictator, of Japan, a position he would hold from 1192 CE to 1199 CE. He would, therefore, be the first shogun of the Kamakura Shogunate (1192-1333 CE). The position of shogun was the first to offer an alternative system of government to that of the Japanese imperial court. The title of shogun or 'military protector' had been used before (seii tai shogun) but had only been a temporary title for military commanders on campaign against the Ezo/Emishi (Ainu) in the north of Japan. Yoritomo was able to hold the title with its new wider meaning thanks to his agreement with the young Emperor Go-Toba (r. 1183-1198 CE) who bestowed it in return for Yoritomo's military protection. Technically, the emperor was above the shogun, but in practice, it was the reverse as whoever had control of the army also controlled the state. The emperors did maintain a ceremonial function, and their endorsement was still sought by shoguns to give a veneer of legitimacy to their own rule.

After all he had done to establish himself as Japan's supremo, Minamoto no Yoritomo did not have very long to enjoy his position as he died in a riding accident in 1199 CE. He was succeeded by his eldest son Minamoto no Yorie (r. 1202-1203 CE), but only after a power struggle. When Yoritomo died, his wife, Hojo Masako (1157-1225 CE), and her father, Hojo Tokimasa, had decided to rule themselves, and so they created the position of shogunal regent and promoted the interests of the Hojo clan. In this arrangement, much copied throughout the Kamakura period, the regent shogun had the real power and the shogun was a mere puppet. Hojo Masako had retired to a convent when her husband had died, but her reinvolvement in politics earned her the nickname the 'nun shogun.' Ambitious, able, and ruthless, Masako was a formidable politician who let nothing stand in her way, not even her father whom she exiled when the pair fell out.

Minamoto no Sanetomo was the second son of Yoritomo and brother of Yorie, who became shogun in 1203 CE with his mother Hojo Masako and Hojo Tokimasa acting as his regents. Sanetomo's 16-year reign came to a brutal end with his assassination in 1219 CE at the hands of his own nephew Kugyo, the son of Minamoto no Yorie. When the assassin was himself assassinated, it left the Yoritomo line extinct, and all key government positions were subsequently held by Hojo family members.

Emperor Go-Toba took the opportunity to launch an attempted coup in 1221 CE - the so-called Jokyu Disturbance - which attempted to exploit the ill-feeling caused by the mysterious murder of the shogun. Lacking the military wherewithal to challenge Hojo Masako, the coup ultimately failed and ended in the then-retired emperor's exile to the distant Oki Islands. At least there he found the time and space to write his celebrated poems over the remaining 18 years of his life.

There would then follow a long line of regent shoguns who ruled on behalf of minors or puppet shoguns. The last Kamakura shogun was Hojo Moritoki (1327-1333 CE). The power of the shoguns, although changing families several times, would last until the Meiji Restoration of 1868 CE. Japan had become wholly dominated by its warriors, a situation reflected in its literature. The period would produce much martial-themed histories and collections of short stories, the most famous work being The Tale of the Heike (Heike monogatari) which first appeared c. 1218 CE and tells of the struggle to establish the Kamakura shogunate.

The Kamakura Government

The shogunate government, also known as bakufu, which means 'tent government' in reference to its origins as a title held by a commander in the field, was based on the feudal relationship between lord and vassal. The former gave lands - confiscated from defeated warlords belonging to families rival to the shoguns - to the latter in return for military service. In the case of a shogun or lord having many estates he might give some of them to a steward (jito) - a position open to men and women - to manage and collect the local taxes with that official then entitled to fees and tenure. The role of steward was frequently given as a reward to loyal members of the shogunate. Many jito became powerful in their own right, and their descendants became daimyo or influential feudal landowners, while another layer of landowners was the military governors or constables (shugo) who had policing and administrative responsibilities in their particular province.

Quite early on it became obvious that the shogun or regent shogun had rather too much on his plate to govern the whole country without any well-defined state apparatus. Accordingly, in 1184 CE the Kumonjo or Public Documents Office was established. This was then renamed and widened in function as the Mandokoro (Administrative Board) in 1191 CE as it became the main administration centre. Later still, it would be given charge of the state treasury. In 1184 CE the Monchujo was set up which looked after all legal matters. A new position, a vice-regent to the shogun (rensho) was created in 1225 CE. In the same year, the Council of State was formed, the Hyojoshu, which had as its members the top officials, warriors, and scholars of the moment. In 1232 CE a new law code was established, the Joei Code (Joei shikimoku), which had 51 articles and established who owned what land, defined the relationship between lords, vassals, and samurai, limited the role of the emperor, and established the taking of legal decisions based on precedence. Finally, in 1249 CE a High Court, the Hikitsukeshu was formed which was especially concerned with any disputes related to land and taxes.

Kamakura

Kamakura, the coastal town located on Sagami Bay which gave its name to the period, is 48 kilometres from what would become Tokyo (Edo). It was the base of the Minamoto clan, and it became the capital after Minamoto no Yoritomo sought to distance himself from the former capital at Heiankyo (Kyoto) and any civil servants and officials that might continue to entertain loyalties to the previous regime. The imperial court remained at Heiankyo where titles were dispensed, certain taxes collected, and civilian judicial disputes were settled.

Kamakura, protected on three sides by mountains and the sea on the fourth side, was a perfect choice for a military-minded leader. Extra protection was provided by earth fortification walls and two wooden castles: Sugimoto and Sumiyoshi. These defences would come in handy when the city was under siege in 1333 CE at the end of the Kamakura period. The fortifications did their job, but the army of Nitta Yoshisada (l. 1301-1337 CE) circumvented them by going around a cape at low tide and attacking the city from the beach. The city went into decline after the fall of the Kamakura Shogunate, but the 1252 CE Kotokuin Temple continues to pull in visitors thanks to its massive bronze statue of Amida Buddha which is 11.3 metres tall (or 37 ft), excluding the high stone base.

The Economy

The Kamakura period was generally a good one for the Japanese economy, with trade continuing with China, where gold, mercury, fans, swords, timber, and lacquerware were exchanged for Chinese silk, brocades, perfumes, porcelain, tea, and copper coinage. Coinage was used more frequently, as were bills of credit, sometimes with the unfortunate consequence that people, especially samurai, got into bad debts as they spent beyond their means.

The Kamakura shoguns implemented several land reforms, notably making better use of previously neglected agricultural lands. Technological developments also helped, such as the introduction of a hardier strain of rice from China at the end of the 12th century CE, the widespread use of double-cropping and fertilizers (compost, manure, and ash), and better tools made of better iron than previously. Less land was left fallow because of inheritance disputes when a male relative was lacking. Women were able to own estates in their own right as they continued to be allowed to head families if there was no suitable male relative for the position. Women could inherit and keep their own property no matter what happened to their male relatives or husband.

Meanwhile, in urban settings, trade guilds (za) were established, initially for craftspeople and traders to secure the patronage of a monastery or local lord. Formed by anywhere from 10 to 100 workers or companies, the guilds had the effect of increasing specialization and improving standards. Villages began to grow in size as the road networks improved, a development helped by the fact there were, in effect, two capitals (Kamakura and Heiankyo). The result of the peace and prosperity the country enjoyed was a boom in Japan's population from the start to the end of the Kamakura period: around 7 million to 8.2 million.

Religion

It was during the Kamakura period that two significant new sects of Zen Buddhism were developed: the Jodo Sect (aka Pure Land), founded c. 1175 CE by the priest Honen (1133-1212 CE), and the Jodo Shin Sect (aka True Pure Land), founded in 1224 CE by Shinran (1173-1263 CE), the pupil of Honen. Both sects simplified the religion and stressed that simply chanting the Buddha's name (nembutsu) - multiple times for Jodo and a single sincere invocation in the case of Jodo Shin - would permit the person to be reborn in the Amida Buddha's Pure Land paradise. In addition, this enlightenment and advancement to heaven was open to all regardless of their social status.

The most important Zen monastery was the Kencho-ji in Kamakura, built by the regent Hoji Tokiyori (l. 1227-1263 CE) in 1253 CE. Zen principles of austerity and restraint became very popular with samurai, and its attention to wabi - the aesthetic principle of beauty, simplicity, and withdrawal from the bustle of life - made the Japanese Tea Ceremony a common aristocratic pastime. The austerity of Zen would also influence Japanese ink painting and calligraphy in the Kamakura period while painting, especially portraiture, became more realistic. Shinto continued to be as important as it was in previous periods, with Kamakura notably receiving the Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine.

The Mongol Invasions

The Kamakura period saw one of the greatest threat to Japan's existence, the two Mongol invasions of Kublai Khan in 1274 and 1281 CE. Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294 CE) had sent a letter to the Japanese government warning of this consequence if they did not pay tribute, but both the shogun and emperor ignored the demand. Fortunately for Japan, when the two invasion fleets each met a typhoon and disaster (but not before the second had landed on the beaches of Kyushu), the winds that either sunk or blew the Mongol ships safely away from Japanese shores were given the name kamikaze or 'divine winds.' It seems that the Mongol ships were not particularly well-built either and so proved much less seaworthy than they should have been. The period of high suspense between the two invasions, and indeed the expectation of a third attack, did harm the country as an army had to be kept in constant readiness and payment to soldiers became a serious problem for the government leading to widespread discontent. The agricultural sector was also severely disrupted by the defence preparations. Rivals to the Hojo clan now had their best opportunity to challenge the political status quo.

Decline & the Ashikaga Shogunate

The disaffection caused by the necessity to keep Japan on a war footing was exploited by Emperor Go-Daigo (r. 1318-1339 CE) who sought to return to the good old days of the emperors before Minamoto no Yoritomo had started the shoguns. The emperor made two attempts to grab power, one in 1324 CE and another in 1331 CE. Neither was successful, and he was exiled for his troubles. Then came what has become known as the Kenmu Restoration, which lasted from 1333 to 1336 CE. Go-Daigo returned from exile and tried to enlist the aid of warlords disgruntled with the Kamakura Shogunate. The emperor found a willing ally in the traitorous army commander Ashikaga Takauji, actually sent by the Kamakura Shogunate to deal with Go-Daigo. Takauji attacked Heiankyo while another rebel warlord, Nitta Yoshisada, attacked Kamakura. Victorious, Takauji wanted to be the new shogun but Go-Daigo refused to give him this title because he did not want to return to a position of subservience. Takauji defeated Go-Daigo's chief ally Yoshisada in battle and captured Heiankyo in 1336 CE; the former emperor was exiled for a second time (although he then established his own court at Yoshino). Ashikaga Takauji found himself a more compliant emperor, Komyo, to act as the state's figurehead and became shogun in 1338 CE, thus inaugurating the Ashikaga Shogunate (aka Muromachi Shogunate, 1338-1573 CE). He would hold the position for the next 20 years, and this new chapter in Japan's history would become known as the Muromachi Period (1333-1573 CE).

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.