Prostitution in ancient Athens was legal and regulated by the state. During the Greek Archaic Period (c. 800-479 BCE) brothels were instituted and taxed by the lawgiver Solon (l. c. 630 - c. 560 BCE), and this policy continued into the Classical Period (480-323 BCE). For many Athenian women, prostitution was the only way to make a living.

Athens was a prosperous center for trade that drew a large population of young, single men who served as crew aboard merchant ships, while, at the same time, young Athenian males usually married after the age of 30. To provide sexual release for the one and sexual experience before marriage for the other, Solon legalized prostitution and opened public brothels. There was no stigma attached to clients of prostitutes nor, overall, the call of prostitutes. There were two types of prostitutes in Athens, the pornai, found in brothels or on street corners, and the hetairai, higher-class courtesans. A hetaira was a female companion, and sex was only one aspect of the services she provided. As a hetaira could be quite expensive to hire, most men visited the pornai.

Female prostitutes were recognized as pursuing a legal profession and providing a necessary service while male prostitutes were generally looked down upon for "playing the woman’s part" in sex as their clients were almost exclusively male. Many pornai were slaves, some who had been freed and others not, who were either forced into the work by their masters or found they had no way to make a living other than through the sale of sex. Hetairai were usually upper-class, educated women who wanted control of their lives and their own finances and generally lived as they pleased.

Women in Ancient Athens

Women in ancient Athens were essentially legal minors who were supervised by a male guardian, first the father and then the husband, and if she outlived both, her eldest son or perhaps an uncle. Women in ancient Greece had no political voice and could not engage in financial transactions except with other women and at certain times and places. In the agora, for example, there was a section where women could buy and sell produce from their gardens, wool they had spun, artifacts and jewelry, or whatever they wanted, but they could not sell these to a man nor outside of their specified area.

In the home, the women’s quarters were separate from the rest of the house and could be locked from the outside (the man of the house held the key) because women in everyday life were thought to be exceptionally lustful, weak in their constitution, and easily led astray. A woman was expected to marry, have and rear children, and manage the home. Scholar Robin Waterfield comments:

When a man came of age, he had a variety of different and overlapping roles: as a participant in the administration of the city, as a soldier, as a worker, as a family member, as a member of groups of other like-minded men. Most women had only marriage, childbirth, and family life to look forward to. Marriage was supposed to fulfill a woman’s nature in the same way that war and politics fulfilled a man’s nature. In both drama and real life, the first tears for a dead girl were shed because she would never marry. Women had a civic duty – to produce the next generation of Athenian citizens – and that was considered to be their main role. (162)

The only area of public life women could actively participate in was the religious sphere. Women were central to both the Lesser Panathenaea and the Great Panathenaea festivals and could freely participate in the rituals of the Cult of Athena, even serving as priestesses. Women wove the great peplos (garment) for Athena’s statue in the Parthenon and carried it in the procession through the agora and up the Panathenaic Way to the Acropolis. Women also were encouraged to gather for the festival of Thesmophoria each autumn which celebrated the goddesses Demeter and Persephone and was thematically linked to the Eleusinian Mysteries. The Thesmophoria was an all-female festival, while the Mysteries welcomed both sexes equally.

Women who found Athenian social rules too restrictive had the legal option of becoming a prostitute, which was considered on par with any other profession in the city such as potter, weaver, or carpenter. Lower-class women had more freedom than the upper-class because they needed to help feed the family, and their husbands could not afford to insist on the traditional role as breadwinner and so there may have been some female potters and weavers and farmers, but these were relatively few as compared with the number of women who chose, or were forced into, prostitution. A woman who outlived her husband and father and had no sons could try to make a living by spinning wool or could become a prostitute along with her daughters. The writer Athenaeus of Naucratis (l. c. 2nd century CE) relates how mothers who had lost husbands and sons in Greek warfare and were too old to take up the trade themselves pressed their daughters into prostitution to survive.

Pornai

As noted, the largest class of prostitutes in ancient Athens were the pornai (meaning "to sell") who offered their services in brothels, on street corners, by city walls, in taverns, and at private parties. Solon set the price of a session with a prostitute at one obol. Six obols, minted as silver coins, equaled one drachma which was a day’s wage for a laborer. Brothels and independent prostitutes paid income tax, which was used to fund public buildings, monuments, and to repair roads although, initially, Solon seems to have intended the tax for the building of temples to honor the gods, especially the patron deity of the city, Athena. When they were not engaged in their trade or pursuing their own interests, prostitutes could earn money by spinning wool and weaving, traditional occupations of an ordinary woman in Athens and elsewhere in ancient Greece. Their works could then be sold to other women to supplement their income.

Not all pornai accepted obols as payment, however, and preferred barter in commodities such as food, wine, cosmetics, or garments. Most, however, did accept currency and were well-known for going to any lengths to make themselves desirable to be able to command a higher price for their services so they could put away some money to purchase younger female slaves they would train. These younger girls were then expected to take care of their mistress once she could no longer attract clientele and so it would continue generation to generation. The comic poet Alexis (l. c. 375 - c. 275 BCE) who lived and wrote in Athens, describes the life of prostitutes in a passage from one of his plays, which exist now only in fragments:

First of all, they care about making money and robbing their neighbors. Everything else has second priority. They string up traps for everyone. Once they start making money, they take in new prostitutes who are getting their first start in the profession. They remodel these girls immediately, and their manners and looks remain no longer the same. Suppose one of them is small; cork is sewn into her shoes. Tall? She wears thin slippers and goes around with her head pitched towards her shoulder; that reduces her height. No hips? She puts on a bustle and the onlookers make comments about her nice bottom. They have false breasts for them like the comic actors’; they set them on straight out and pull their dresses forward as if with punting poles. Eyebrows too light? They paint them with lamp black. Too dark? She smears on white lead. Skin too white? She rubs on rouge. If a part of her body is pretty, she shows it bare. Nice teeth? Then she is forced to keep laughing so present company can see the mouth she’s proud of. If she doesn’t like laughing, she spends the day inside, like the meat at the butcher’s when goats’ heads are on sale; she keeps a thin slip of myrtle wood propped up between her lips so that in time she will grin, whether she wants to or not. (Fragment 103 PCG.G, Lefkowitz & Fant, 209)

Although Alexis was known for his comedy and this passage is most likely a speech of one of his characters, it is still an accurate depiction of the life of a lower-class prostitute in ancient Athens. The more attractive a prostitute could make herself, the more she could charge clients. Many learned to play an instrument, dance, and perform acrobatics if they did not know how already, so they would be hired as entertainers at parties. The Symposium of both Plato (l. 428/427-348/347 BCE) and Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE) mention female performers who were pornai (possibly hetairai, though unlikely) hired for the evening. In Plato’s work, the girl is sent away at the beginning of the party so the men can discuss their views on love. In Xenophon’s Symposium, the male and female entertainers perform dance, song, and acrobatics for the guests and then leave after, presumably, being paid. At many parties, however, a guest would hire a girl, or a young man, for the rest of the night and take them to bed.

Male pornai were not as numerous as females but worked in brothels and on the streets in the same way. Male prostitutes could and did provide services to female clients but were primarily patronized by older men. The exploitation of slave prostitutes was common for both male and female slaves and there was no legal protection of slaves. Many of the male pornai were slaves who were forced to work in brothels but, whether their profession was involuntary or chosen, they had a shorter career term than female prostitutes. A male pornai was only considered desirable from puberty until he began growing a beard, so roughly between 13-20 years old. Female pornai, by contrast, could work for many years before they had to rely on the younger girls they trained for support and, in the case of the hetairai, continued for life since eloquent speech and quick wit were as important, and often even more important, than sex among the services they offered.

Hetairai

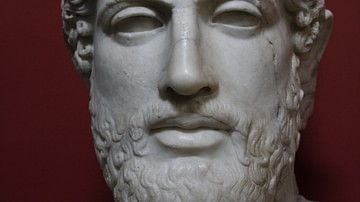

Some scholars in the present day make no distinction between pornai and hetairai, claiming they were all just prostitutes, and the hetairai were simply more expensive. This claim is unsupported by the primary documents, however, which emphasize the intelligence, charm, and wit of a hetaira while pornai are only referenced regarding sex. The most famous hetaira in ancient Athens was Aspasia of Miletus (l. c. 470-410/400 BCE) the consort of the statesman Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE). Aspasia was a metic (someone not born in Athens), and many metic women seem to have often found work in Athens as hetairai, just as Aspasia did.

Another well-known hetaira, who actually may never have existed, was Philaenis (l. 4th century BCE), also a metic, from Samos who lived in Athens. She was famous for writing erotic works which survive only in fragments or as references in the works of other authors. It is possible Philaenis was a pseudonym, and the work was written by a man, but this claim rests largely on ancient apologetic texts written to practice one’s skill at persuasion in rhetoric, not first-hand accounts. Scholar I. M. Plant argues for Philaenis’ existence as a hetaira and writer, noting:

Pornography was often attributed to prostitutes and Philaenis appears to have been perhaps the best known of these. Samos was notorious for the poor moral standards of its women and for a high number of prostitutes, and it is not surprising to find Philaenis linked to that island…her name, a feminine diminutive of the Greek word for love, was regularly used by prostitutes. [Even if she was not an actual person] 'Philaenis' existed as a female literary figure, reinforcing one of the typical images of women in the Classical world: the prostitute. (45)

Plant’s point is that works such as those attributed to Philaenis contributed to the view of women as sex objects and highlighted their participation in prostitution. For the pornai who were not slaves, prostitution was often the only means of survival, but for the hetairai, at least in some cases, it was a chosen profession, which offered women the chance to live as they pleased without male control over their finances and life choices. The term hetaira is translated as "courtesan" but actually means "female companion", and a hetaira might be hired by a wealthy client to accompany him to a party, a social function, or religious festival having nothing to do with sexual intercourse.

Hetairai are usually referenced as educated women, often metics, who chose their profession, but this was not always the case. Another famous hetaira, Lais, was a young girl of Hyccara in Sicily when the Athenians sacked the city, kidnapped her, and sold her into slavery. She worked her way up from an unwilling pornai to a hetaira and one of the most famous prostitutes of the ancient world who was able to challenge the Greek tragedy playwright Euripides in a battle of wits and was the near-constant companion of the philosopher Aristippus of Cyrene. The fragments of the works of Lais still extant are thought to be later pieces written by someone using her name. Plant comments, "Lais was such a famous prostitute that a work attributed to someone of that name would have implied that it was the work of a prostitute" (119). Further, it would mean that a high-class hetaira was respected well enough that people would want to read her work and that others, hoping to gain an audience, would write under a prostitute’s name.

Conclusion

Even so, and although prostitution was legal and socially acceptable, it was still unpalatable to many Athenian citizens. The children of prostitutes were not considered citizens because, in most cases, their mothers were not, and their paternity could not be proven. Both pornai and hetairai had children that, if female, were raised to carry on their mother’s profession and care for her in old age and, if male, were abandoned or sold to infertile Athenian wives who needed to produce an heir for their husbands.

Male prostitutes, as noted, were generally viewed unfavorably as having forfeited their masculine power by accepting a passive role in sex. The famous legal case known as Against Timarchus of 346-345 BCE highlights how male prostitutes were viewed in that the statesman and orator Aeschines claims that Timarchus is unfit to participate in the affairs of the city because he was formerly a male prostitute. Aeschines makes clear that he is not attacking male-male romantic or sexual relationships but only the role played by the male prostitute who cannot be considered a viable citizen of Athens as he has accepted the role of a woman. Women were regarded as biologically, spiritually, and mentally inferior to men and so had no place in the active social and political life of the city as Waterfield notes:

Women were considered to be closer to beasts than a fully rational man and to have strong appetites for sex, food, and alcohol. An Athenian man’s honor depended in part on the honor of his womenfolk, and he lived in fear of adultery on the part of his wife, although marriage was widely acknowledged as his best chance of "taming" a woman. (165)

Prostitutes, on the other hand, posed no such threat. A man could spend an hour with a prostitute and never have to give her a second thought afterwards. It never seems to have occurred to any Athenian male that this practice was degrading to women nor that their laws often forced young women into prostitution after the death of the male head of the family simply to survive.

Although this policy and practice is considered objectionable in the present day, and even though the occupation was viewed unfavorably by many at the time, prostitution in ancient Athens was regarded overall as a rational response to a biological need without any attendant ethical concerns. It should be noted, however, that this view was not held by all the Greek city-states, and in some, such as Sparta, prostitution was rejected as demeaning to both men and women.