A Hetaira (pl. hetairai) was an educated female prostitute in ancient Greece and a common participant in symposia or drinking parties in private homes. Sometimes referred to in English as a courtesan, the Greek term hetaira was a euphemism and meant 'companion'. Typically slaves but not always, their status could be ambiguous and is ill-defined in surviving Greek sources. Besides their more obvious abilities as prostitutes, hetairai were skilled in entertaining men with their music, dancing, culture, and wit. Hetairai are referenced in many forms of Greek art and literature and so are distinct from the more common brothel or street prostitute (pornē) who offered only physical pleasure to their clients and did so at a much lower price than the hetairai.

Status of Prostitutes

There were sex-worker slaves, former slaves and free women of all types in ancient Greece, but they can be broadly categorised into three groups: the brothel or street prostitute (pornē) who offered their bodies for sexual pleasure, the concubine (pallakē) who lived permanently in a particular household, and the hetaira, a high-class prostitute who, besides sex, offered clients the benefit of their education in music (especially the flute), dance, and general culture. For this reason, the term hetaira - a euphemism in Attic Greek meaning 'female companion' - is often translated as 'courtesan', although the exact status of these women in society is not precisely known and most ancient sources refer only to Classical Athens and Corinth. In addition, ancient sources are not consistent in their application of these categories, even when speaking of the same individual. It is also true that women (and men) could move between the different types of prostitute mentioned above or even gain their freedom (and lose it again). Finally, there was yet another but entirely separate group, the sacred prostitutes who gave their bodies as part of religious cults.

Naturally, one of the greatest distinctions between types of prostitutes was their price. A pornē could cost as little as one obol, the smallest coin in Athens. A top-class hetaira, in contrast, might cost 500 drachma or 3,000 obols. That hetairai commanded high prices is further attested by the policy of city-states to tax prostitution.

Many hetairai were likely women of a higher class who had become slaves after the conquest of their city-state in Greece or from other states outside Greece. Taking female captives to make them enslaved prostitutes is attested as early as the 8th century BCE. There would also have been women who either chose the profession and so became independent earners or those who were forced into it by circumstances such as debts or having no male relatives to support them. The distinction between the classes of prostitutes may have reflected changes in Greek society where a growing middle class permitted more males to pay for the services of prostitutes than previously. By creating a more sophisticated and expensive type of prostitute, upper-class males could thus distinguish themselves from the middle-class practice of visiting brothels and host hetairai in their homes.

While some today might consider a hetaira somehow more 'worthy' than a pornē, this was not necessarily so in ancient Greece. Prostitution was an open and legal part of Greek society where public brothels were often funded by the state because they were seen as a necessary part of daily life. Similarly, hetairai were considered normal participants in the accepted entertainments of those who could afford them. Prostitution was, like gambling, for example, considered acceptable but it was also thought potentially harmful if overdone. It was not considered a substitute for a stable family life but an accompaniment.

In Greek sources, prostitution of any kind is generally given a negative connotation, and its practitioners are often regarded as unclean and tacky. Writers often highlight the dangers (and possibilities for comedy) of becoming infatuated with a prostitute, neglecting one's wife, or frittering away all of one's wealth on bodily pleasures. Further, to be labelled or suspected of being a prostitute (male or female) was seen as an insult, at least in Greek literature and between public figures. On the other hand, it is perhaps important to remember that the vast majority of surviving Greek sources were written and created by men for a male audience. Exactly what hetairai thought of themselves or how other women regarded them is not known.

Famous Hetairai

It is known that hetairai often formed lasting relationships with married men and were not mere 'one-night-only' performers. Some would have been given money and gifts to remain one man's exclusive sexual partner but who still did not live in his home. Indeed, some hetairai had such a lasting effect that they were given their own house or received dedications such as public monuments erected in their honour, even at such famous religious sites as Delphi. From this, we can imagine that some hetairai were famous in their day, and we know by name many hetairai who formed lasting relationships with the most famous of Athenians, from philosophers to playwrights.

The 5th-century BCE historian Herodotus devotes a few passages of text to a hetaira named Rhodopis (Histories, 2.134-5). She is Thracian and described as "well endowed with the blessings of Aphrodite." Herodotus reports that she was once a fellow slave with the famed storyteller Aesop (c. 620-564 BCE) and that she became very famous and rich, although he ridicules suggestions that she built a large stone pyramid in Egypt.

Another famous hetaira, at least according to some ancient writers, was Aspasia of Miletus (c. 470-410 BCE), a noted teacher of rhetoric, a writer, and an intellectual. Aspasia was from an aristocratic family, and she became the mistress and then co-habitant of the Athenian statesman Pericles (495-429 BCE) from around 445 or 450 BCE until his death. The couple had a son, also called Pericles, who was eventually made a citizen of Athens. Aspasia may only have been called a hetaira by writers who had an axe to grind against Pericles and his pro-democracy stance. Nevertheless, the association of Aspasia with that title confirms that hetairai were expected to be intellectually accomplished.

A third example of a famed hetaira is Phryne, who was born in Thespies but lived most of her life in Athens in the 4th century BCE. Phryne was famously attached to the sculptor Praxiteles, creator of the Hermes and Dionysos statue at Olympia. Legend has it that Phryne was the model for Praxiteles' much-copied statue of Aphrodite. Phryne also had an attachment to the orator Hyperides which led to her famous legal defence. Phryne was accused of impiety, a serious offence and worthy of the death penalty in Athens. Hyperides defended her in court, his strategy being to disrobe Phryne so that the jury, dazzled by her naked beauty, let her off the charges. Phryne went on to become immensely rich, so wealthy in fact, she offered to rebuild the city of Thebes after Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) demolished it in 335 BCE. Her condition for this generous act was that the Thebans should then erect a sign over the city's main gate proclaiming 'Alexander pulled me down, Phryne the hetaira re-erected me' (Souli, 50). Thinking this would not provide a good role model for their wives, the Thebans declined the offer.

Hetairai & the Symposium

Besides these more glamorous and celebrated members of the profession, most hetairai lived anonymous lives serving males at symposia, that is informal and male-only drinking parties. We know a good deal about symposia because they often appear in Greek art and are a common setting in literature such as the Greek comedy plays of Aristophanes (c. 460 - c. 380 BCE) and even give the title to one of Plato's dialogues, the 416 BCE Symposium. The hetairai involved in these events may well have been of a different status than those who commanded the affections of a specific male for a period of time.

Organised from the 7th century BCE onwards, symposia were held in the private homes of aristocrats where guests ate and drank together. There was even a special room for these events, the andrōn, which was furnished with between seven and eleven low cushioned couches. The couches were arranged around the edge of the room to create an empty central space so that each guest could see all the others. Wine was an integral part of the proceedings and was drunk (mixed with water) from a kylix, which is a shallow cup with a short stem and two horizontal handles. The kylix was specifically designed so that it could easily be put down or picked up when reclining on a low couch.

A symposium could be very informal and be little more than a drinking party but some could be more formal; still others descended into orgies. Certainly, they were, after the food was taken away, an opportunity for males to discuss events of the day and such subjects as politics, philosophy, religion, and the arts. One man might lead the discussion, not necessarily the host but someone chosen by lot. Guests might tell a story, recite a poem, or perform some music on a lyre. The guests might sing a song together with each guest taking on different verses. There could be games, too, such as flipping the dregs of one's kylix at a target such as an amphora stood by one wall. Into this convivial atmosphere the hetairai stepped, the only women permitted to attend.

The Skills of Hetairai

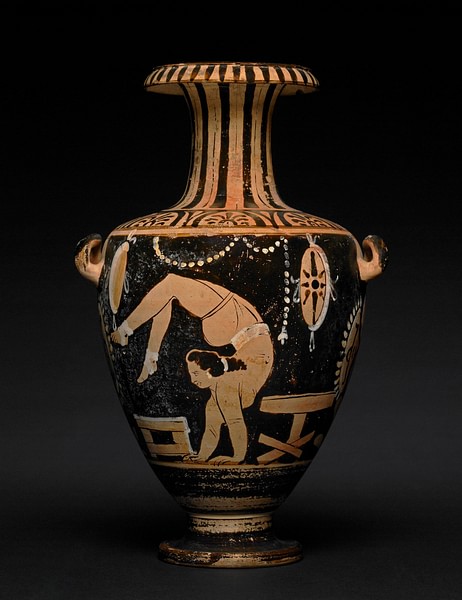

Naturally, guests expected their host to provide hetairai who were beautiful, charming, witty, and desirable. Greek pottery scenes show hetairai serving wine to guests at symposia, and we know they wore fine clothes and gold jewellery. The hetairai then became more active participants as the evening wore on. They were trained to play the aulos or flute and they could also dance, perform gymnastics, and hold a discussion on cultural topics. Of course, besides all this, the hetairai were in attendance to offer the guests sexual pleasures. That the hetairai were slaves to be used as anyone saw fit is evidenced in painted pottery scenes (not usually on display in museums) which show them naked and performing all manner of sexual acrobatics with single or multiple clients and each other. In addition, some scenes show them suffering what, in any other context, would be described as physical assault and sexual abuse. The notion, then, that these women somehow earned the respect of the men who used them through their cultural accomplishments is perhaps a romantic one that does not reflect the everyday reality of sexual slavery in antiquity. As the historian, Madeleine M. Henry notes:

While not denying agency and dignity to women who chose prostitution or who were prostituted, recent studies suggest that women all along the spectrum were structurally exploited and marginalised to a marked degree.

(Bagnall, 3196).