How did a mere 167 Spaniards conquer an empire of 10 million people? The Spanish were outnumbered 200-to-1 yet they were able to seize the Inca capital, Cuzco, and dispose of the Inca ruler within only a year. Kim MacQuarrie's The Last Days of the Incas, recounts the Spanish conquest of the Inca empire beginning with the landing of conquistador Francisco Pizarro and his army of 167 men in 1532 CE through a 36-year guerrilla war in the Upper Amazon region of what is present-day Peru. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Kim MacQuarrie about the demise of one of history's greatest empires.

JBW: How did you first become interested in the Inca and their downfall in the 16th century CE? As I understand it, you lived in Latin America, in the Upper Amazon, prior to writing The Last Days of the Incas? I suppose then you have had a longstanding interest in South America and indigenous peoples.

KM: I lived for four years in Peru in the late 1980s, while doing graduate work in anthropology. After doing graduate work at La Católica University in Lima, I spent about seven months living with a recently contacted tribe, the Yora, in Peru's Upper Amazon. The Yora still passed on stories of how their ancestors used to trade with a people who lived in a “high, cold, land.” These were the Incas. Not far from where the Yora lived was the last capital of the Inca Empire, Vilcabamba, which had been hidden in the jungle for nearly 400 years. It was only rediscovered in the 1960s. So it was living and traveling in that area of the world and listening to the Yora's stories that first got me interested in the Incas.

JBW: When reading The Last Days of the Incas, I was very surprised to learn that Francisco Pizarro (1471-1541 CE) was illiterate, illegitimate, a poor horseman, and lacked formal military training. I also found it curious that Pizarro's brothers accompanied him to Peru and that they also played a key role in the Spanish conquest of the Incan Empire. When reviewing Pizarro's role in the Spanish conquest of Peru, what about his personality and actions stand out in your estimation? If we should know anything about Francisco Pizarro, what should it be?

KM: The interesting thing about Pizarro is that he was a fourth cousin of Hernán Cortés (1485-1547 CE), who conquered the Aztec Empire of Mesoamerica in 1519-1521 CE, more than a decade before Pizarro began his conquest of the Inca Empire. Not only were they from the same impoverished area of Spain, Extremadura, but so were quite a few other conquistadors, such as Hernando de Soto, Vasco Núñez de Balboa, and Francisco de Orellana. It was a region that seemed to have produced a lot of tough, resolute, taciturn, and ambitious men. Pizarro enlisted the help of his brothers and other men from Extremadura just before his third and final voyage to Peru. He needed men he trusted and could count on, so his brothers formed the core of the Peru campaign.

What most people don't realize is that 16th-century CE conquistadors actually formed corporations before they set off to plunder. They drew up contracts and divided the spoils according to what each individual conquistador brought on the expedition - horses or rifles or money, etc. The key to understanding Pizarro is that he was not only 54 years old by the time of his capture of the Inca emperor, Atahualpa, but that he was also "CEO" of the expedition. By 16th-century CE standards, Pizarro was “old” for a conquistador. It had taken him a lifetime to get himself into the position of leading an expedition that actually had the chance of making its participants millionaires. So, as he headed up into the Andes in search of the Inca emperor, he was the equivalent of an aging "CEO" of perhaps his final “start-up” endeavor. This was his biggest and - he had to know - probably his final opportunity to really strike it big. For Pizarro, therefore - from a hardscrabble, impoverished background - there was no turning back.

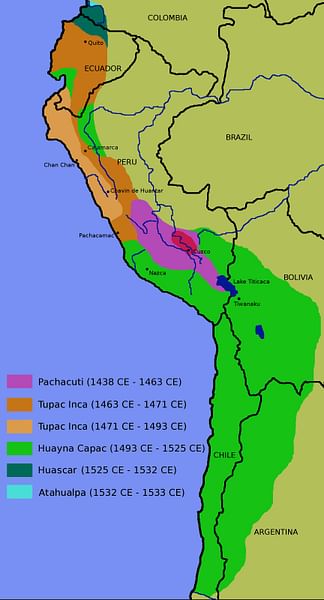

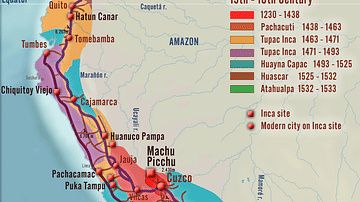

JBW: The Incan Emperor Atahualpa (r. 1532-1533 CE) is a portrait in contrast to Francisco Pizarro; born into wealth and prestige from a young age, Atahualpa inherited a vast empire that stretched from what is present-day Colombia to Chile, which was twenty times larger than that of the Aztecs in Mesoamerica. Considered divine by his subjects, Atahualpa was believed to be an incarnation of the Inca sun god Inti. How would you characterize Atahualpa in the story of the Spanish Conquest of Peru, and what is his legacy if he has one?

KM: The Incas had an interesting system of primogeniture, that is, the right of succession of royal rule. Technically, the eldest son an Inca ruler had with his “legitimate” wife (which was also his full sister) was slated to inherit the empire. However, more often succession seemed to set off a contest among the rulers' sons. The system almost seemed to encourage whichever son was crafty enough or motivated enough or political enough to win the throne. In Atahualpa's case, his father died abruptly before it had been determined who would rule. That succession vacuum set off a conflict between Atahualpa and his brother, Huascar, which ultimately resulted in a violent Inca civil war. Atahualpa eventually vanquished his brother in battle and had his brother executed. It was at that moment when unknown, bearded invaders from afar arrived in the northern corner of what is now Peru.

Interestingly, once the Spaniards captured Atahulapa they taught him how to play chess and he was very good at it. Chess is all about strategy. However, in his first interaction with the Spaniards, Atahulapa made the fatal mistake of underestimating them. After all, he had roughly 80,000 warriors at the time against a mere 168 Spaniards. Why should he be worried? If anything, he was probably curious. That fatal, strategical mistake, however, ultimately cost him his empire.

JBW: You have compared the Inca Empire with that of the Roman Empire. In which ways were the Incas reminiscent of the ancient Romans?

KM: Roman civilization incorporated the inventions from thousands of years of previous Mediterranean civilizations: law, engineering, warfare, philosophy, architecture, etc. The Romans invented little themselves (although they did invent cement and a calendar that ours is based upon), however, they were masters at administration and at building upon what had gone before. Similarly, the Incas incorporated cultural inventions from thousands of years of pre-Inca cultures.

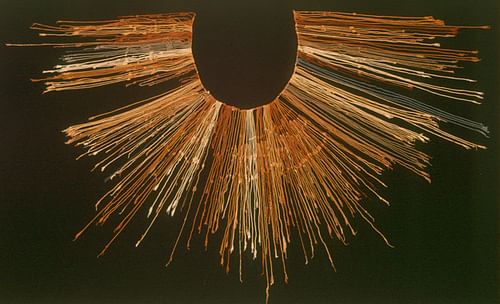

Although renowned today for their stone cutting, metallurgy, warfare, astronomy, agriculture, and road building, most of these techniques had been invented long before they came on the scene. Even their famous quipus - the clusters of knotted cords that allowed them to keep track of vast amounts of data - had been invented thousands of years earlier. Like the Romans, however, the Incas were master administrators, road, and empire builders. By amalgamating and enlarging on what had come before, they eventually built the largest indigenous empire that ever existed in the New World.

JBW: I think it is worth mentioning that the Incas were empire-builders themselves, and they aroused great resentment among many indigenous peoples in the Andes. Do you suspect that Pizarro would not have been successful if there was not already a high degree of indigenous hostility to the Incas throughout the Andes? To what extent did Incan relations with other indigenous peoples play a role in Pizarro's conquest?

KM: The Spaniards already had considerable experience in taking advantage of political divisions to fracture power bases that opposed them. They also had a long track record of seizing indigenous rulers and holding them hostage, so as to gain power over native populations. The classic example is Hernán Cortés' seizure of the Aztec ruler, Montezuma, and of forming alliances with indigenous enemies of the Aztecs, which ultimately helped them defeat their empire. As mentioned earlier in our discussion, Cortés was a second cousin of Pizarro and it's very possible that Pizarro met Cortés before embarking from Spain on his third and final voyage to Peru.

At the very least, it's likely that Pizarro knew about how Cortés defeated the Aztecs. Pizarro not only captured the Inca ruler Atahualpa and held him hostage, similar to what Cortés had done in Mexico, but he also quickly learned that the Incas, too, had enemies, and did his best to ally himself with them. What the indigenous groups both in Mexico and South America did not understand, however, was that Cortés and Pizarro were far more dangerous to them ultimately, than their local enemies - the Aztecs and Incas. In the end, all of the indigenous groups - ”friend” and “foe” alike - were conquered by the Spaniards.

JBW: Can you tell us about Vilcabamba and the last Inca emperors who fought a 36-year guerrilla war again the Spanish?

KM: While many people have heard about Pizarro and may have heard that Pizarro captured an Inca ruler and that the Inca ruler offered a roomful of gold for his release - most people are unaware that the Incas actually created a rebel empire in the Amazon jungle and fought on for more than three decades after the capture of their emperor.

Very few people are aware that renegade Spaniards actually taught the Inca rebels how to ride on horseback, how to fire harquebuses (primitive Spanish rifles) and that the Inca rebels nearly succeeded in wiping out the Spanish conquistadors. It's a fascinating, little-known story and their Amazonian capital, Vilcabamba - about 100 miles from Machu Picchu - was also only recently rediscovered in the 1960s after being “lost” for nearly 400 years.

JBW: Unfortunately, we are unable to read Inca quipu, which would otherwise reveal a great deal of information about Incan culture and civilization. How then did you research your title based on the dearth of indigenous primary sources? Moreover, what additional, specific challenges did you face in researching The Last Days of the Incas?

KM: That is true for the moment about the Incan quipus - the information storage devices that was invented thousands of years before the Incas. However, scientists continue to make advances in deciphering how they were used. It's now well known how the Incas stored numbers on them and it's possible that the Incas also stored phonetic sounds. So it's possible that one day we may actually be able to “read” them. Who knows?

In researching The Last Days of the Incas, I made extensive use of the Spanish “chronicles,” that is, reports sent back to Spain about the Incas and the sequence of events that led to the downfall of their empire. I also made use of certain “chronicles” and reports made on behalf of the Incas or composed from Spanish interviews of native people in the empire - a process that continued for hundreds of years.

Obviously, since the Incas were not “literate” in the sense of leaving behind written records that can be read today, the challenge of reconstructing what happened before, during and after the conquest is the inevitable reliance upon the records of the Spaniards, many of which are inevitably biased and/or were written by authors who understandably had a limited grasp of Inca culture and history at the time. The information I used for Inca history prior to the Spanish arrival was based on both Spanish interviews with indigenous inhabitants of the empire as well as on the on-going discoveries of archaeology and anthropology.

JBW: Kim MacQuarrie, I thank you so much for speaking with me on behalf of Ancient History Encyclopedia. I wish you many happy adventures in research, and I thank you for speaking with me about The Last Days of the Incas.

KM: It was my pleasure, James. And, although I am obviously biased, I hope that if anyone reading this has not yet had a chance to visit Peru - that in the future they do! It is certainly one of the most fascinating areas of the world.

Mr. Kim MacQuarrie is a four-time Emmy Award–winning filmmaker and award-winning author who has lived and worked all over the world. Educated in the US and France, he lived for five years in Peru and spent some of that time living with a recently contacted tribe in the Amazon jungle, only 100 miles from Machu Picchu. He is the author of Life and Death in the Andes and The Last Days of the Incas, as well as three illustrated books about Peru. He currently divides his time between the US, Peru, and Thailand. Learn more about his work and research at KimMacQuarrie.com.