The two sieges of Cusco in 1536-7 were the last great military actions by the Incas as they tried to reclaim their empire from the Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478-1541). The European cavalry proved all but invincible, and the city held out until reinforcements arrived from across the Americas.

The Incas, led by Manco Inca Yupanqui (c. 1516-1544), continued to resist the invasion of their world for a few more decades, mostly using guerilla warfare, but the loss of their great religious and political centre at Cusco proved to be a blow from which they would never recover.

Heart of an Empire

Cusco (Cuzco or Qosqo) was the religious and administrative capital of the Inca Empire which flourished in ancient Peru between c. 1400 and 1534. The Incas had built the largest empire ever seen in the Americas and governed some 10 million people. Cusco, established in the 14th century on a site with a much older history, had a population of around 240,000 by the 16th century. Strategically important at the juncture of three rivers, the Spanish conquistadors knew that if they captured the heart of the Inca empire, the rest would soon collapse. Here was the administrative, religious, and geographical centre of the Inca world with the sacred Coricancha (Qorikancha) complex and large ceremonial plazas. Covering some 40 hectares, the capital was protected on the northern side by the Sacsayhuamán (Saqsawaman) fortress. This massive structure had three terraces set in a zigzag fashion so that each wall had up to 40 segments, allowing the defenders to catch attackers in a crossfire. Only one small doorway on each terrace gave access to the interior. The fortress was said to have had a capacity for 1,000 warriors.

The Incas had already been hit by the first terrible Spanish weapon: an epidemic of diseases, such as smallpox, which had spread from Central America even faster than the European invaders themselves. This wave killed a staggering 65-90% of the population. Such a disease killed the Inca ruler Wayna Qhapaq in 1528, and two of his sons, Waskar and Atahualpa, now battled in a damaging civil war for control of an empire already struggling to impose itself on a myriad of different peoples just when the European treasure-hunters arrived.

Pizarro & the Conquistadors

The conquistador Francisco Pizarro, then already in his mid-50s, arrived in Peru with an astonishingly small force of men whose only interest was duplicating the conquest of Mexico by Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) and looting the region of its treasure. Acquiring a legal right from the King of Spain, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556) to become the governor of new lands colonised and to keep one-fifth of the wealth acquired, Pizarro organised his third expedition in 1531, leading just 260 men to the Andes. Moving down the coast of Ecuador, pillaging along the way, the invaders noted the well-built roads and storehouses, sure indicators they were encroaching into the lands of a wealthy empire. On 15 November 1532, first contact was made with the Inca people, and Pizarro sent word he wished to speak with their king.

Atahualpa, who had defeated his brother Waskar, met the Spaniards – speeches were exchanged, and Spanish horsemanship was shown off while the drinks were passed around. This convivial start lasted less than 24 hours. Pizarro attacked the Incas the next day, his cannons and firearms ensuring a total victory where 7,000 Incas were killed against zero Spanish losses. Atahualpa was hit a blow on the head and captured alive. Pizarro (or Atahualpa) stipulated that the king would receive his freedom if a room measuring 6.2 x 4.8 metres were filled with all the treasures the Incas could provide up to a height of 2.5 m. The Incas complied and over the next months with Atahualpa still ruling his empire from captivity, the loot was assembled. Pizarro, meanwhile, sent out reconnaissance missions to see what else might be of interest in the Inca Empire, notably to the capital Cusco. Rather unsportingly, Atahualpa was executed on 26 July 1533. Pizarro was later rebuked by his own monarch for this act of treachery, but it may have been the conquistador's intention to subdue the Incas with this single blow against the ruler they considered nothing less than a god.

Hernando Pizarro (1501-1578) reported back to his brother that Cusco was a city shimmering with gold. As the Spaniards marched south they received food and military assistance from peoples only too glad to free themselves from the yoke of Inca rule. A brief resistance was met and defeated en route to Cusco, and then the capital itself fell without much fuss on 15 November 1533. The Coricancha was stripped of its golden sheeting, and anything else of value was pocketed from exotic feathers to emeralds. Everything about the campaign so far seemed remarkably easy, but the Inca house of cards was not yet totally collapsed.

Manco Inca Yupanqui

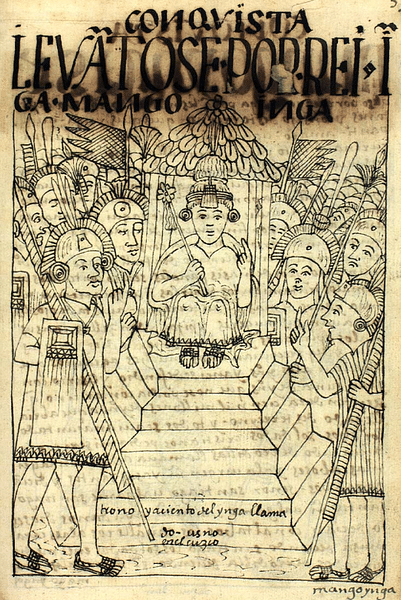

Pizarro's strategy was to install an Inca puppet ruler at Cusco, first Thupa Wallpa (brother of Waskar) and then Wayna Qhapaq. Meanwhile, the conquistadors set off to explore any other profitable sites in this land of gold, Pizarro himself heading for the coast. The northern territories put up stiffer resistance to the invaders where traditional Inca warfare was adapted to meet the new challenge of steel, bullets, and cavalry. Then, in April 1535, the situation began to turn. Manco Inca Yupanqui (also spelt Manqo Inka), the new Inca leader from 16 November 1533 and another intended Pizarro puppet, formed an army of resistance and besieged both Cusco and Ciudad de Los Reyes (Lima), now the main Spanish stronghold.

Manco Inca would never have risen to become a ruler in the old Inca Empire since he had too many older brothers. Indeed, Manco was an outcast following the takeover by Atahualpa and the subsequent purge on rival Inca royals. Manco was not yet 20 years old, but he did have military experience, notably in the Inca conquest of the Antisuyu people, who lived in what is today Bolivia. He seemed an ideal candidate for Pizarro to select as yet another puppet ruler. Manco Inca initially allowed his army to be used by the conquistadors in their battles with Atahualpa's Incas.

Unfortunately for the Spaniards, though, Manco Inca had his own ambitions, and he saw the split amongst the invaders as an opportunity not to be missed. Manco Inca joined forces with the disgruntled conquistador Diego de Almagro (c. 1475-1538), a great rival of Pizarro who had been made lieutenant-governor of Cusco in January 1535. Then, after Charles V decided the new colony should be split between Pizarro and Almagro, the latter left Cusco in July to explore Chile. The Inca capital was now in the hands of Juan Pizarro and Gonzalo Pizarro (c. 1512-1548) who both pushed Manco Inca rather too far. The Inca ruler was under additional pressure from his own people to take up arms and rid the region of these troublesome invaders with their insatiable appetite for gold and silver. Manco Inca attempted to secretly leave the city, but he was captured and imprisoned by the Spanish. Other Inca leaders had made their escape, notably the general and uncle of Manco, Tiso. These leaders began to organise an empire-wide revolt and attack isolated conquistadors who had settled on farms. Then Hernando Pizarro returned from Spain with instructions from Charles V that the Inca ruler be treated as the monarch he was. Manco Inca was released from his prison.

While Hernando was away on an expedition against the Inca rebels, Manco Inca convinced the Spanish that he be allowed to go on a religious pilgrimage. The ruler promised he would bring back a sacred golden statue for the conquistadors, in fact, he took many sacred Inca relics and mummies with him as he left Cusco. On 18 April, and with only a two-man escort, Manco Inca made good his escape. Now, with their traditional sapa inca leader, the Inca army could fully mobilise. Tens of thousands of warriors began to gather on the outskirts of Cusco.

The Siege of 1536

The siege of Cusco began on 6 May 1536 – there would later be criticism of the Inca high command that they had not attacked the city soon enough, but they had first wished to assemble their full military force. Manco Inca was present in person at the siege, but he left the front line command to more experienced warriors. The Inca army's first tactic was to open the city's canals, flooding the area so that the feared Spanish horses would find the terrain more difficult.

The Incas were equipped with lances, slings, bows, javelins, hardwood swords, halberds, clubs, battleaxes, bolas, and unique weapons like the rompecabezas, a wooden staff with a spiked ball at the top, and the haybinto, a spiked stone or bronze piece attached to a rope that could be swung at arm's length. Although they had no specialised siege equipment, encircling and attacking a stronghold had been a common feature of Inca warfare prior to the Europeans' arrival. One innovation that was particularly useful in these sieges was the use of huge shields to protect the attackers from missiles launched by the defenders. The shields were made of thick cotton pads stretched over wooden frames. The Incas also wore body armour made of thickened leather or with small metal plates added to a tunic of wool or cotton (an uncu). They wore helmets of quilted cotton, wood, or twisted cane, all materials strong enough to resist direct blows from stone missiles. Finally, the Incas had no qualms about using weapons, armour, and even horses captured from the Spaniards.

The Spaniards were armed with metal swords and armour, gunpowder weapons, and, most important of all, 3-3.5 m (10-12 ft) lances wielded by cavalry. Well-protected against Inca missiles, a European soldier could still be vulnerable, for example, to a direct blow to the face or when he was caught on foot and overwhelmed by sheer numbers. In the early part of the siege, the cavalry units proved as effective as they had in Mexico and earlier battles in South America, as here described by Cieza de León:

…setting up two companies with crossbows, bucklers, and pikes, and another two with horses, he [the commander Rojas] approached the largest squadron of the Indians from two sides so that the crossbows could do it much harm…he [then] attacked on two sides with the horses in a closed and tight thong. Trampling and killing with the lances, they opened up the squadron…the Indians were defeated and dispersed. (Sheppard, 45)

The First Attack

The Inca army, perhaps numbering 100,000 warriors, was finally ready to oust the Spaniards, led by Hernando Pizarro, who numbered just 196 fighting men (110 infantrymen and 86 cavalry riders). The defenders were bolstered by some 2,000 Indian allies (mostly Cañaris and Chachapoyas), a number of African slaves, and a single artillery piece. Slowly and deliberately, the Inca army tightened its perimeter around the city and closed in on the Spanish. The Sacsayhuamán fortress was easily taken since Hernando had failed to garrison it. From these heights, the Incas launched heated stones using their slings, and these set fire to the thatch roofs of the city. Storming through the smoke-filled streets, the Incas engaged the enemy in a vicious hand-to-hand battle. When the battle reached the open spaces of the sacred ceremonial plazas, the Spanish cavalry could finally operate but the Europeans were obliged to retreat to the better defences of the heart of the sacred city. The besieged were greatly helped by native peoples who brought food supplies into the city at night. Meanwhile, the Incas built spiked obstructions and pits in every street to prevent a breakout by the Spanish cavalry. Hernando then ordered his native infantry and cavalry to be used in tandem to try and unblock specific passages, a tactic which eventually allowed the Spanish to break out into the more open terrain of the city's outskirts.

Spanish Victory

Juan Pizarro was charged with leading a force of 50 cavalry and 120 infantry to regain the Sacsayhuamán fortress. Juan attacked the fortifications by surprise from the outer side after making it look like his force was leaving for Lima. Nevertheless, the first two Spanish attacks failed under an onslaught of Inca slingshots. A third attack on the main gate was successful, although Juan was mortally wounded in the action, and his brother Gonzalo took over command. Both sides now focussed on the Sacsayhuamán, each commander strengthening their troops there. Hernando Pizarro took over the attack and, using ladders at night, managed to scale the fortification walls, forcing the Incas to retreat to a section with three towers. Eventually, the Incas ran low on stone ammunition for their slings, and they were routed, many preferring to jump to their deaths off the high walls rather than be butchered by a Spanish sword.

Crucially, the besieging Inca armies were largely composed of farmers pressed into military service, and they could not abandon their harvest without starving their communities. By August, the siege had to be abandoned and the remnants of the Inca army moved back to Ollantaytambo (Ullantaytampu) some 45 miles to the northwest. Manco Inca ordered a huge sack be left at Cusco where the Spanish would find it. The conquistadors found their gift, but inside were the decapitated heads of their countrymen killed by the Incas elsewhere. Also in the sack were letters and a glimmer of hope, Spanish reinforcements were on the way.

Francisco Pizarro had men-at-arms now spread all over South America, and his options were limited, but when he heard of the siege at Cusco in early May 1536, he sent two relief forces, one with 60 horses, the other with 80. Both forces were annihilated by Inca armies under the command of the Inca general Quizo Yupanqui, who ambushed and trapped both columns in ravines. When Pizarro heard the terrible news, he wrote to all the governors of the New World in a desperate attempt to get new recruits into South America. Even if his calls were met with a favourable response, it would take several months for reinforcements to arrive. Pizarro and Cusco must stand alone against the Inca fightback.

The Second Siege

Pizarro in Lima was attacked by a massive army led by Quizo in September 1536, but the Spanish cavalry once again proved all but invincible, and the Inca general was killed. Meanwhile, back at Cusco, Hernando Pizarro now led more and more ambitious forays out of the city to capture much-needed supplies. The Incas were, though, starting to build up enough forces to besiege the city for a second time. Knowing from experience that an Inca army was all but useless without its leaders, Hernando decided to go after Manco Inca at Ollantaytambo with a force of 70 cavalry and 4,000 allied infantry in January 1537. Warned of their arrival, the Incas had already entrenched themselves behind a series of formidable terraced fortifications, and the Spaniards could not penetrate the stronghold. Even worse, Manco Inca had diverted the Vilcanota River and flooded what had previously been excellent terrain for cavalry. Hernando was obliged to return to Cusco.

By November 1536, Pizarro, still in Lima, had recalled all his men from various expeditions and received reinforcements from the north and even Spain. He dispatched an army of 350 Europeans, which included over 100 cavalry, to relieve Cusco. This force was supplemented by another 200 reinforcements on the way to the Inca capital. At the same time, Almagro was returning from his expedition to Chile with 400 men. Facing this formidable amount of cavalry, in March 1537, Manco Inca was obliged to again withdraw from Cusco. He hoped the Spanish might battle each other in their competition for power and gold. The second siege was broken, and on 18 April 1537, Almagro took over control of Cuzco from Hernando and Gonzalo Pizarro. Almagro imprisoned Hernando Pizarro at Cusco on 25 July 1537, but there was no significant battle, as the Incas had hoped, although Almagro was later outmanoeuvred and executed for his audacity. In all, the defenders of Cusco had lost no more than 20 Spaniards compared to thousands on the Inca side. Still, over 700 Spaniards had been killed during the uprising in the territories around Cusco and in the defeated relief forces sent from Lima.

Aftermath

By the end of July 1537, Manco Inca was forced to flee further south, first to Vitcos and then the Vilcabamba valley where he set up an Inca enclave. From here, the Incas pursued a decade-long guerrilla war against the Spanish. Back in Cusco, the Spanish made Manco Inca's brother Paullu their new puppet ruler, and the European conquerors continued to profit from long-standing resentment of Inca overlordship and the total loss of confidence in many of the Incas themselves after the fall of their capital. Nevertheless, Manco Inca's own successors, starting with his son Titu Cusi Yupanqui, would continue to resist. Not until the 1550s did the Spanish fully gain control of their Viceroyalty of Peru (established in 1542). Cusco had suffered terribly from the sieges, and it was now rebuilt, but with a completely foreign architecture as the Spanish Empire began to spread and deepen its roots in preparation for centuries of colonial rule.