Hernando de Soto (c. 1500-1542) was a Spanish conquistador who fought in Panama and Nicaragua and accompanied Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478-1541) in the conquest of the Inca civilization in Peru. He famously explored North America, including the Mississippi River where he died in 1542 never having found the fabled golden cities that had driven him on for four years of exploration.

Early Life & Central America

Hernando de Soto was born c. 1500 in either Jerez de los Caballeros or Badajoz, both in Extremadura, Spain. He was born into a family of the minor nobility and so had the status of hidalgo. Around 1514, the young Hernando sailed for the adventure of the New World with a fleet led by Pedro Arias de Ávila (aka Pedrarias Dávila, b. 1442) destined for Panama. In 1517, he explored what is today Colombia before returning to Panama. In 1524, de Soto joined an expedition led by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba bound for what is today Nicaragua. As so frequently happened in the frontier world of highly competitive conquistadors, Córdoba did not get on with de Soto and even had him arrested at one point, but he broke out of his prison thanks to the help of Francisco de Compañón.

De Soto had done his career prospects no harm when he rejoined forces with Pedrarais, now a powerful colonial administrator and governor of Panama. Pedrarias was in stiff competition with Pedro de Alvarado (c. 1485-1541), the governor of Guatemala, for the territory that lay between their two domains (today's El Salvador and Honduras). Pedrarias was also not at all happy with Córdoba exceeding his authority, a fact reported to him by de Soto.

De Soto was rewarded for his exploits in Nicaragua by being made the chief magistrate or alcalde of León, the regional capital. This position gave de Soto several encomiendas, that is the right to exploit local forced labour. The entire region was proving a disappointment to the Spanish in terms of precious metals available, but money was made from slavery. De Soto was one of the chief slave traders, selling captured Central Americans to colonial settlements on the mainland and in the Spanish Caribbean. One of de Soto's ships, La Concepción, transported nearly 400 slaves per voyage.

One Spanish chronicler gives the following if rather flattering description of de Soto: "a handsome man, dark in complexion…of a cheerful countenance, an endurer of hardships and very valiant" (Howard, 67). De Soto was of small stature but already noted for his daring, horsemanship, and chivalrous qualities (towards fellow Europeans only, it seems).

Pizarro & the Incas

In the 1530s, de Soto was one of Francisco Pizarro's key commanders and co-funder of the expedition that began the conquest of the Inca Empire. In return for his financial backing, de Soto was promised the governorship of the largest city they encountered. De Soto arrived in South America shortly after Pizarro with a useful supplementary force of two ships carrying 100 Spaniards and around 50 horses in December 1531. Also on board was the first Spanish woman to reach Peru, Juana Hernández.

The combined army of conquistadors attacked the port of Tumbes in the Gulf of Guayaquil in February 1532. Next, they moved inland and noted the well-built roads and storehouses along the way, which indicated they were surely entering the lands of a wealthy empire. Finally, on 15 November 1532, first contact was made with the Inca people, and Pizarro sent word he wished to speak with their king at Cajamarca in the highlands of Peru. De Soto was the man sent to meet the Inca ruler, who was just then, as it happened, enjoying the local springs outside Cajamarca. Atahualpa (r. 1532-1533) had just defeated his brother Waskar in a 6-year civil war. De Soto entered Atahualpa's camp with 15 men and one rather poor interpreter. After being kept waiting for several hours for a royal audience, de Soto was joined by another 20 conquistadors led by Hernando Pizarro (Francisco's brother)

Eventually, Atahualpa deigned to come out of his luxurious tent. First contact was friendly, with drinks and a round of speeches. The Spanish delivered their obligatory guilt-erasing monologue, the 1514 Requerimiento, which outlined a history of Christianity, the superiority of the Pope, and the obligation from this day onwards for all indigenous peoples to submit themselves to Spanish authority. Incomprehensible to the audience, most conquistadors simply skimmed through the most pertinent elements of the document, often beginning the shooting before they had reached the last lines. At this early stage in the conquest, one can imagine de Soto was more pedantic and bored his audience to the maximum. In some accounts, de Soto then offered his gold finger ring to Atahualpa as a token of goodwill (in other versions it is Hernando Pizarro who offers the jewellery).

There was next a display of Spanish horsemanship put on by de Soto, Hernando Pizarro, and Sebastián de Belalcázar. De Soto tried to intimidate the watching Incas by pretending to charge his horse at the crowd and having it rise on its hind legs. One chronicler even describes de Soto's snorting steed ruffling the feathers of the Inca ruler's sacred headdress. Atahualpa remained impassive to the charge, but the next day he ordered the execution of those Inca dignitaries beside him who had flinched during de Soto's performance; their wives and children were executed, too. De Soto reported back to Pizarro, who decided the next day to attack the Inca army. Atahualpa likely had the same sort of plan for the Spanish. In the battle that followed, the Spaniards routed an 80,000-strong Inca force. 7,000 Incas were killed and no Spaniards. The overwhelming superiority of gunpowder weapons, crossbows, and cavalry (commanded in two wings by Pizarro and de Soto) could not have been made more evident.

Atahualpa was captured and had to provide a massive treasure store to secure his release. When this vast quantity of gold and silver was duly delivered, Pizarro decided to execute Atahualpa anyway on 26 July 1533. De Soto and a number of other senior conquistadors had argued the Inca ruler should be sent to Spain, but Pizarro was determined to cut off the political, religious, and military head of the culture he was about to destroy. It is perhaps significant that de Soto was sent on a reconnaissance mission while the rapid trial and sentence were carried out. Also significant, de Soto reported he had found no evidence of a second Inca army waiting to attack the Spanish.

As the conquest continued, the conquistadors approached the Inca capital of Cusco. De Soto, leading an advance force, was the first Spaniard to enter this great Andean metropolis in September 1533. The conquistadors were impressed with the density of the city and its finely-built stone palaces and storehouses. Pizarro went on to capture Cusco easily enough in November 1533, but an Inca uprising in 1536-7 led to a siege of the city. Cusco finally surrendered in April 1537.

In the period between the initial fall of Cusco and its recapture, de Soto had been appointed the corregidor of the Inca capital (in this context its governor) while Pizarro had gone off to explore the coast where he founded Lima. De Soto distributed encomiendas and established some sort of order in the fractured city from his residence in the Amarukancha palace. De Soto had also led an allied Inca-Spanish army against the rebel Inca general Quizquiz, who was resisting the Spanish invasion from his base in Quito. Eventually, the Spaniards subdued the rebels, and the Inca Empire collapsed completely. The Viceroyalty of Peru was formed in 1542.

Governor of Cuba

De Soto, with his share of 17,740 pesos from Atahualpa's ransom, was now a wealthy man, but after the fall of Cusco, he wanted to add to his success and become a leading colonial administrator in his own territory. Pizarro jealously guarded his privileges in Peru, and de Soto had been overlooked for command of a new expedition to Chile, that role being awarded to Diego de Almagro (c. 1475-1538). Consequently, de Soto was obliged to look elsewhere. In December 1535 he left South America and his mistress Tocto Chimpu, the daughter of the late Inca leader Waskar. Back in Seville, de Soto lived in a huge mansion surrounded by an equally massive entourage of servants while he pondered his future.

In 1537, de Soto got his wish for further adventure when he gained an audience with the king of Spain, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556). He was made the governor of Cuba and a Knight of Santiago. In addition, the Spanish Crown awarded de Soto the coveted status of adelantado, which was the right of conquest. De Soto had his eye on Colombia, but the king had plans for North America, specifically the Gulf Coast, where it was rumoured there was much gold to be found. De Soto was granted a capitulación, the right to explore and exploit a huge swathe of land from the river de las Palmas in Mexico to the Florida Keys. In return, de Soto had to give the Crown 20% of the wealth he acquired.

Fellow conquistador Juan Ponce de León (1474-1521) had led two expeditions to explore what is today Florida in 1513 and 1521. The Spanish authorities had so far been slow to follow up on León's discoveries, perhaps because of the hostile reception he had received. The reputation of the area sank even lower in Spanish estimates in 1527-8 when an expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez ended in nearly all the participants succumbing to native attacks, starvation, or shipwreck. One survivor, Álvar Núñez Cabeza (c. 1490-1556), persisted with maddeningly vague hints that there were golden cities still to be conquered beyond the Florida peninsula, a description of dubious authenticity, which the Council of the Indies back in Spain, nevertheless, noted down for future reference.

By 1537, the Spanish were ready to try once again to explore and exploit North America. De Soto's expedition sailed from Spain in April 1538, restocked at the Canaries and then Cuba, where a round of parties celebrated his appointment as governor. A bad omen, perhaps, was the running aground of the flagship San Cristóbal in the harbour of Santiago, then the capital, which resulted in the loss of the expedition's wine. De Soto's new wife, Isabela de Bobadilla, daughter of Pedrarias, had travelled from Seville, but she was left to govern Cuba as the deputy governor until her husband's return.

Sailing from Havana in a fleet of nine ships, de Soto probably landed near what is today Tampa, Florida at the end of May 1539. This was a well-funded venture, which included 600 fighting men, many of whom had colonial experience in Peru. The ships carried a vast array of expensive equipment and provisions, everything from salted beef to the iron chains they hoped would soon bind captured slaves.

Exploring North America

Almost immediately after landing, the Spaniards began their usual strategy of killing natives, grabbing interpreters, and seeking out gold and silver. A useful early 'capture' was Juan Ortiz, a native of Seville who had been on a previous Spanish expedition but who had then been captured. He had escaped a death sentence and now lived as the Indians did, even tattooing his body. He became de Soto's chief interpreter. Ominously, Ortiz assured his countrymen that there was no gold to be found in these parts. De Soto decided to press on northwards anyway, frequently reassured by the usual native tales that the next tribe over the next hill were rich in gold but not they. As de Soto passed through, he left behind devastating European diseases and a lasting suspicion of these strange bearded men from another world.

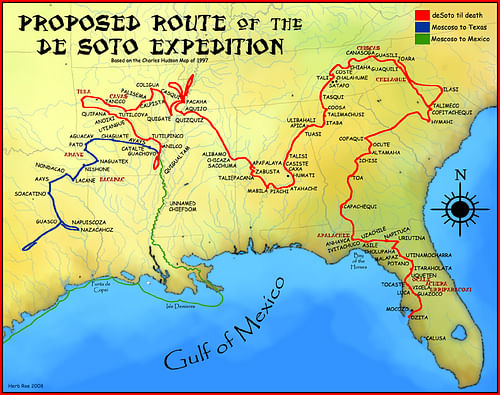

De Soto kept moving on, eventually encountering the Apalachee Indians and countless other groups, reaching as far north as today's North Carolina. Over the next four years, they laboriously trekked through an enormous stretch of land covering what are today the US states of Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas. De Soto time and again employed his strategy of capturing a tribal leader and demanding food and porters to carry on his expedition. The invaders came across excellent agricultural lands, fine pottery, and impressive burial mounds, but still they did not find the fabled golden cities. North America did not seem to have the riches of Mexico or Peru. De Soto eventually returned to the Mississippi River but died, perhaps of fever, near Natchez on 21 May 1542. He was 42 years old. Hernando de Soto's body was committed to the waters of the Mississippi. The expedition, now under de Soto's nominated deputy Luis de Moscoso, was terminated, and the survivors turned back, eventually reaching Pánuco in Mexico in September 1543.

Hernando de Soto's Expedition to La Florida (1539-1542) had been an expensive disaster for both the participants and the communities encountered, but it did at least result in the first detailed documentation of the peoples and cultures of this part of North America before it was all but erased by those Europeans who followed.