The Spanish Main refers, in its widest sense, to the Spanish Empire in the Americas from Florida in the north to the northern coast of Brazil in the south, including the Caribbean. The term was initially more limited and referred only to the mainland Spanish territories in northern South America. It was a name particularly popular with writers of pirate fiction as a handy and romantic term to cover the field of operation of privateers, buccaneers, and pirates from the 16th to 18th centuries.

Geographical Area

The term 'Spanish Main' was applied to Spanish colonial possessions in the Americas from around 1520 to 1730 and the end of the Golden Age of Piracy. At first, it had a more limited meaning. The term literally meant the "mainland of the Spanish Empire" and derived from the Spanish Tierra Firme, meaning the "mainland". Consequently, the expression was used by English privateers in the 16th century to mean only the northern coast of South America (approximately from Panama to Trinidad), although the coastal waters thereof were also included. The Caribbean islands were not then included within the term's geographical reference since these were obviously islands and not the American mainland. The buccaneers of the 17th century then used 'Spanish Main' to refer to the Caribbean Sea, in effect, inverting the original meaning. 18th-century fiction writers began to use the term even more indiscriminately to mean all of the Spanish Empire from Florida in the north to the border with Portuguese Brazil in the south. It also now referred to the entire ocean in that area and so came to include all of the Caribbean with the exception of the Lesser Antilles, which had been colonised by other European powers.

The Spanish Empire

In 1492, Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) sailed across the Atlantic in the service of the Spanish Crown, and instead of finding a route to Asia as he had hoped, he encountered the Americas. Columbus himself embarked on more voyages of exploration, and he was followed by others. Spain's only real rival in the race to exploit the riches of the Americas was the Portuguese, but the two nations audaciously carved up the globe to create two spheres of interest. The division was set by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas and extended in the 1529 Treaty of Zaragoça (Saragosa).

In 1494, a Spanish settlement was founded at La Isabela on the island of Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic/Haiti). In 1498 Santo Domingo was founded on the island. In 1508 Puerto Rico was settled; in 1511 Cuba followed. Cattle, horses, and mules were introduced and bred. Plantations were created growing sugar cane, just as the Portuguese had been doing in the Atlantic islands like Madeira. Tobacco was another booming plantation crop. Slaves were used to work these plantations, both indigenous peoples and West Africans. Perhaps 2 million African slaves were shipped to the Spanish Main in the 16th and 17th centuries. Having established themselves in the Caribbean, the Spanish then sent tentative expeditions to the American mainland, starting in Panama where the Pacific Ocean was first seen by European eyes, those of Vasco Núñez de Balboa, in 1513. The colonisation of the 'Spanish Indies', as the Americas was then known, had begun.

The indigenous peoples of the coast very often fought back this tide of colonisation, resorting to tactics like ambush in the face of a merciless enemy with weapons of technology centuries ahead, but the visitors from the Old World were here to stay. Native peoples were ruthlessly robbed, butchered, or enslaved; those that remained alive were taught the religion of these strange men from afar, the explorers, the priests, and the hidalgo adventurers. In just one example, the Arawak Indians of the Caribbean were wiped out within a generation by the sword, exploitation, and European diseases. The dreadful pattern of conquest was set.

Spanish forces, the Conquistadores, acted upon rumours of fabled cities of gold deep in the American interior and so they attacked and destroyed the Aztec civilization in Mexico from 1519 onwards. Weakened from within by political factions, the Aztecs were defeated by superior weaponry, cavalry, and tactics. Once again, diseases ripped through the population. The Spanish cleverly allied themselves with long-time rivals to the Aztecs such as the Tarascan civilization, and the overstretched and often brutal Aztec Empire collapsed, to be replaced by an even more brutal new order. The Conquistadores’ leader was Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) whose religious zeal was matched by his thirst for riches and glory. The wealth of ancient Mexico was ruthlessly plundered as ships began to transport treasure back to Spain. The Aztec capital Tenochtitlan was made the new capital of the colony of New Spain, and Cortés was made its first governor in May 1523. In 1535, Don Antonio de Mendoza was made the first viceroy of New Spain.

Next was the turn of Central America and then South America. In 1532, a Spanish force led by Francisco Pizarro (1478-1542) encountered the Inca Empire, which, stretching from Quito to Santiago, was the largest in the world. Once again, a combination of superior weapons and internal disputes saw a young and fragile empire totally collapse within a generation. Most decisive of all were the European diseases like smallpox which had already spread from Mexico to South America even before the Spanish themselves arrived. In the greatest humanitarian disaster to ever hit the Americas, a staggering 65-90% of the population would die from this invisible enemy. For the Spanish at the time, the astonishing fact was the sheer quantity of gold and silver they saw in temples, houses, and on the bodies of the Incas themselves. With the fall of Cuzco in November 1533 and the installation of a puppet ruler, the Spanish thought they were well on the way to controlling a vast new region of the world. However, the new order had just as many practical difficulties as the old one in controlling a vast geographical area with a myriad of different peoples, cultures, and languages. Rebellions and wars bedevilled the Spanish until 1572 and the execution of the last claimant to the Inca throne.

Stripping the Americas

The Spanish established colonial government based on a system of principalities headed by a governor or viceroy. They also built fortifications to protect themselves from counter-attacks as the Spanish Empire stripped the Americas of anything valuable, indiscriminately melting down objects of gold and silver, in particular. When these easy sources were exhausted, trade was pursued, and natural resources were exploited like timber, pearls, and gems. Silver was acquired from mines in Peru and Mexico, both of which were worked using slave labour. The metal was frequently minted into pesos or pieces of eight, a coin that became the de facto international currency of the Americas.

The Spanish insisted on a trade monopoly in their empire and would not permit other European merchants to buy and sell goods to the newly growing colonial towns across the Americas. European rivals instead set their covetous eyes on the two annual treasure fleets of Spanish galleons that took the riches of the Americas to Spain (c. 1520-1789). As Spain also shipped precious eastern goods in the Manila galleons from the Philippines to Acapulco, Mexico (1565 to 1815), the Atlantic treasure fleets, besides gold, silver, and gems, also transported a fortune in silk, spices, and porcelain. In the first century of conquest, the Spanish extracted an astonishing 10.5 million troy ounces of gold from South America. In terms of silver, 25,000 tons were shipped to Spain by 1600. In addition, on average 3 million silver pesos went back to the Philippines each year to buy goods to fill up the Manila galleons. The relative rarity of silver in China meant that it could be used to purchase twice as much gold in the Far East as one could buy with the same amount of silver in Europe. The Spanish were not only extracting great riches from the Americas, they were shifting commodities around the globe to make even more profit.

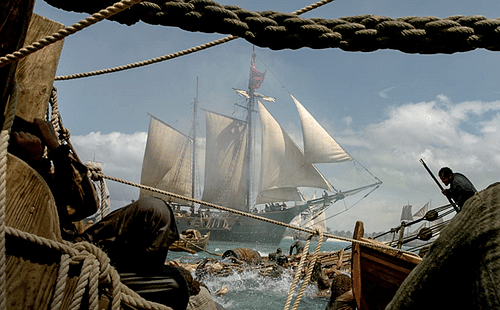

A tempting target, attacks on the Spanish treasure fleets were unofficially endorsed by rival European governments to weaken Spain and persuade it to open up the Americas to trade. An escort and convoy system was largely successful in protecting the treasure fleets, but when the privateers did capture a prize, it was a huge one. Another tempting target was the ports where these riches were accumulated ready for loading onto the treasure ships.

The Key Ports

By the 17th century, the Spanish Empire in the Americas was composed of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico and Central America) with the seat of the viceroy in Mexico City (formerly Tenochtitlan). The Viceroyalty of Peru (the former Inca territory) was established in 1543. New Granada (Venezuela and Colombia) had another viceroy from 1739, this one headquartered at Cartagena. The Viceroyalty of Rio de La Plata (Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay) was not formed until 1776. Panama and Honduras each had a governor, as did Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico.

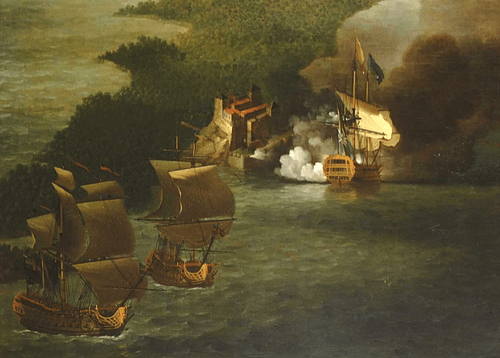

Mexico City might have been the administrative capital of Spanish America, but the heart of the Spanish Main in many ways was Havana, Cuba. It enjoyed the best strategic location in the Caribbean basin, and its governor was senior to those on the other Caribbean islands. Havana was also the gathering point for the treasure fleets before they sailed to Spain, and, from 1610, had the largest shipyard in the Americas. The French privateer Jacques de Sores brutally attacked Havana in July 1555, and this made the Spanish determined to protect their colonial jewel. The Fuerza Real was built in 1558, the first bastion fortress to be built in the Americas. The great Morro Castle was added from 1589. Now, no other pirate, privateer, or naval commander ever dared attack Havana and its 30,000 residents for nearly two centuries.

Cartagena, in what is today Colombia, was one of the most important ports on the Spanish Main because it was the collecting point for gold, silver, emeralds, and pearls from Colombia-Venezuela. For this reason, it was known as the 'Queen of the Indies'. It was briefly captured by Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596) in 1586 and so was given much-improved fortifications in 1602, which made the port all but impregnable.

Another key treasure port was Portobelo (aka Puerto Bello) in Panama. From 1596, it replaced Nombre de Dios (founded 1510) as the collecting point for the huge quantities of silver gathered from the Potosi mines in Peru (discovered in 1545). The silver was brought in galleons from Peru to Panama (founded 1519) and then taken overland across the isthmus to Portobelo using mules. Portobelo was also the site of a large annual trade fair. Consequently, Portobelo was an irresistible target for foreign marauders. Francis Drake seized the silver mule train in 1573, loot that amounted to 15 tons of silver and 100,000 gold pesos (enough cash to build 30 warships of the period).

San Juan de Ulúa was the fortress island that protected the harbour of Veracruz on the Atlantic coast of what is today Mexico, the third of the great treasure ports. Veracruz was founded in 1519 by Cortés, and it became the collection point both for silver gathered from Mexico and the eastern precious goods brought by the Manila galleons and transported across land to Veracruz. In 1568, San Juan de Ulúa was the site of an infamous Spanish attack on a trading fleet led by the Englishman John Hawkins (1532-1595 CE), a treacherous defeat the Elizabethan sea dogs used as an excuse to attack all things Spanish for the next half-century.

There were, of course, many other ports and towns throughout the Main. The heavily fortified St. Augustine in Florida helped maintain Spain's tentative foothold on the coast of North America where they first had to resist the expansion of the French Huguenots who had settled in the area from 1562, and then the British who moved ever-southwards down America's eastern coast. San Juan on Puerto Rico welcomed the Spanish treasure fleets to the Caribbean. Maracaibo on the coast of what is today Venezuela had around 4,000 residents and was the centre of the regional pearl trade.

Typically, all Spanish settlements in the Americas were laid out in a regular grid pattern of blocks and streets with a large central plaza for the community's administrative and religious buildings. Royal regulations on town planning were issued from 1573. A mayor headed a group of councillors who governed the town, which was granted, as in Spain, the right to produce its own coat of arms. To help remind everyone where their ultimate loyalty lay, the royal coat of arms of Spain was presented over the town's fortress gate and any official buildings.

The 17th-century Attacks

Into the 17th century, Spain's colonial monopoly began to be challenged by other European powers, particularly in the Caribbean islands. England, France, and the Netherlands were all at war with Spain for much of the century, and the Americas was an important front given the funds that crossed the Atlantic. In addition, Spain's navy was now third in size to the fleets of England and France. The English moved in on St. Kitts (aka Saint Christopher, 1623), Barbados (1624), Nevis (1628), Antigua, and Montserrat (1632). The French established themselves on Martinique and Guadeloupe in 1635. From 1599, Dutch ships took salt from Araya on the coast of Venezuela – a commodity vital for their herring industry – and they took a keen interest in the resources of Brazil. Of more direct concern to the Spanish Main was the Dutch colonisation of St. Eustatia, Tobago, and Curaçao between 1632 and 1634.

By the 1630s, there were some 18,000 Europeans living in the Lesser Antilles; by the 1660s, this figure had swelled to 100,000. Many of these East Caribbean islands were now used as bases by European powers to attack the Spanish Main and as havens for smugglers and pirates. The Spanish responded with regular attacks on the islands, but they were rarely successful in achieving anything except an increase in the animosity towards all things Spanish.

The British moved westwards, occupying Bermuda and the Bahamas, and when they took the strategic gem of Jamaica with its wonderful natural harbours in 1655, suddenly the entire Spanish Main was opened up to attacks. Key Spanish ports were persistently targeted by large amphibious forces of multinational privateers and adventurers known as buccaneers who were sponsored – either officially or otherwise – by the colonial authorities. The English buccaneer Henry Morgan (c. 1635-1688) sacked Panama in 1671, and he attacked and ransomed Portobelo in 1680. The Dutch privateer Laurens De Graaf (c. 1651-1702) attacked Veracruz in 1683 and managed to make off with the loot meant for a treasure fleet. A large French combined naval and pirate force captured Cartagena in 1697, the last major buccaneer raid before a formal peace was agreed between Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands. The Spanish responded to these setbacks by building bigger and better fortifications with city walls and suitably enlarged garrisons to man them.

The 18th-century Attacks

The Spanish Empire did revive from its somewhat dilapidated state. King Charles III of Spain (r. 1759-1788) was instrumental in overseeing a massive reinvestment across the Spanish Main, particularly in terms of fortifications and a new system of rotation which saw local garrisons boosted by an influx of better-trained and better-equipped troops from Europe. These forces were commanded by various captain-generals headquartered at the major ports. Defence of the empire, however, was an ongoing battle and a hugely expensive one that seemed to have no end.

In the mid-18th century, the British Admiralty specifically ordered its fleet commanders "to destroy the Spanish settlements in West Indies and distress their shipping by any method whatever" (Wood, 164). The Royal Navy even captured fortress Havana in 1762, but it was returned the next year. The 1763 Treaty of Paris saw Spain give Florida to Britain (they regained it in 1783) but receive in return a slice of French Louisiana. In 1800, Louisiana was ceded to France, but it ended up in the hands of the United States by 1804. The European powers were beginning to arrange their colonial interests like chess pieces, occasionally attempting bold strikes, sometimes making retreats, or biding their time to see how this multiplayer game of empires developed. Meanwhile, the United States, Mexicans, and others eyed which parts of the board they would claim for themselves irrespective of what pieces were sitting where.

Spanish Decline

Into the 19th century, not only did the Spanish have to deal with attacks from rival European powers but the world was also moving on rapidly both politically and economically. They now faced far greater threats from indigenous peoples in the Americas. Colombian rebel forces, for example, besieged and took Cartagena in 1815 and 1821. The Latin American nations declared independence from Spain through the 1820s. There were also threats from rising powers like the United States in the north. In 1819-21, Florida was ceded to the U.S. and for the remainder of the 19th century, the Spanish were left with only Cuba and Puerto Rico.

World trade had also opened up even further, and now the Far East was contributing commodities such as tea and opium to the world economy. India and Brazil were also growing fast, and the plantations of North America, South America, and the Caribbean – all fuelled by the horrific business of slavery – were flooding the world with sugar, tobacco, coffee, and cotton. The days when Spain could monopolise half the world's trade and the Spanish Main seemed the treasure house of the world were but a distant memory.