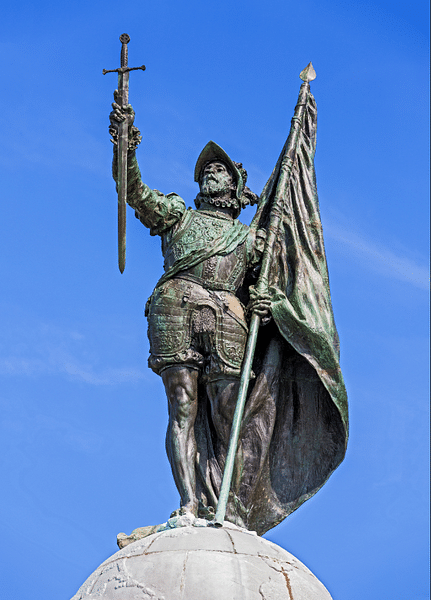

Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475-1519) was a Spanish conquistador who famously discovered the Pacific Ocean after crossing the isthmus of Panama in 1513. An utterly ruthless adventurer and colonizer, Balboa was as much a danger to his fellow conquistadors as he was to the indigenous peoples he came across.

Balboa helped establish the town of Darién, the first permanent Spanish settlement on the American mainland. Extracting gold from Panama and instituting slavery and forced labour to work on plantations, Balboa was ultimately outwitted by a Spanish rival who had him tried and executed for treason.

Early Life

Vasco Núñez de Balboa was born in Extramadura in Spain in the small village of Jerez de los Caballeros in the province of Badajoz. His family belonged to the minor nobility. In 1500-1, Balboa joined the expedition of Rodrigo de Bastidas (1460-1526), which hoped to find pearls along the northern coast of South America (present-day Colombia), then a virtually unknown region to the Europeans. The expedition was a success in charting new coastlines but did not find many of the hoped-for pearls. Balboa next settled on Hispaniola (modern Haiti/Dominican Republic), where he owned a plantation, but his business sense was poor, and he was obliged to abandon the island after he racked up huge debts.

Darién

Fleeing those he owed money, in 1510 Balboa stowed away on a ship led by Martin Fernández de Enciso which was headed for the mainland to give vital aid to the fledgling Spanish colony of Urabá on the Colombian coast. Enciso enlisted the useful Balboa amongst his men, but he was an administrator not a true conquistador like Balboa – who the historian J. H. Parry describes as "a popular desperado" (52). The group of adventurers much preferred to take their orders from a man like Balboa. The serious problem with Urabá was the fierce native tribesmen who used their deadly poisoned arrows with devastating effect. Balboa wisely decided to move what was left of the colony across the Gulf of Urabá where, crucially, the locals did not use poisoned arrows.

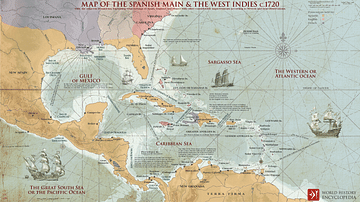

In the area of what is today Panama, Spanish steel and gunpowder weapons, as well as the use of attack dogs, ensured the Europeans enjoyed a string of victories as they established their enclave. The new colony of Santa Maria La Antigua de Darién, or simply Darién, the first permanent Spanish settlement on the North American mainland, was founded. Despite the reality of humid swamplands, this area was soon to be called by the Spanish Castilla del Oro ('Golden Castile') because of the quantity of gold artefacts bartered and looted from the local peoples. Balboa had even written to the king in Spain rather rashly claiming that there were here "rivers of gold" and that indigenous chiefs had "gold growing like maize in their huts which they collect in baskets" (Cervantes, 86).

Balboa was utterly ruthless in his quest for gold and used subterfuge, torture, and diplomacy in equal measure. Still, finding gold in Panama proved rather more difficult than Balboa had first thought. Then, in typical conquistador fashion, Balboa openly usurped Enciso as the community's leader after accusing him of mismanagement and dispatching him back to Hispaniola in irons. The conquistador also sent a note to the Spanish authorities asking for reinforcements so that he could properly subdue this new corner of the Spanish Empire. Another rival conquistador, Diego de Nicuesa (b. 1465), was cast adrift in a tiny boat and allowed to drown.

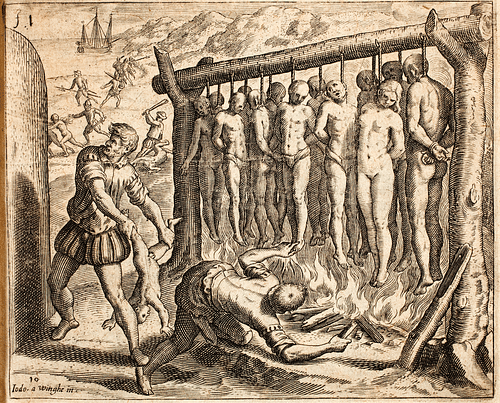

Balboa made determined raids on local tribes to ensure Darién remained a permanent Spanish base for incursions further inland. He did, though, make allies as well as enemies, cleverly playing on old tribal rivalries to ensure the Spanish never faced a united opposition. Indigenous peoples were forced into labouring for the new colony, which began to establish areas for agriculture. Little better than slaves, native labourers were subject to harsh living conditions and brutal punishments; Balboa infamously employed attack dogs as one method of execution.

Balboa was greatly intrigued by stories the Indians told of a great sea to the southwest, and he was determined to investigate. Another intriguing rumour the Spanish heard in Panama was of a golden kingdom far to the south, undoubtedly a reference to the as then undiscovered Inca Civilization.

Crossing Panama to the Pacific

Balboa, realising he now had to make good on his exaggerated descriptions of the wealth of the region, organised an expedition to explore more of Panama and find out if there really was another coast not too far away on 1 September 1513. One expedition member was Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478-1541), who went on to conquer the Incas from 1532. Pizarro was appointed Balboa's second in command. The 200 conquistadors and over 1,000 native bearers crossed the narrow isthmus in as direct a line as possible heading southwest, but it was far from easy as the route involved cutting through dense jungle and crossing rivers and swamps.

The explorers first sighted the Pacific Ocean from a mountain peak on 25 or 27 September 1513 and then on the 29th reached the breaking waves themselves. They were the first documented Europeans to do so. Balboa immediately realised the significance of his discovery and later described himself as "prouder than Hannibal showing Italy and the Alps to his soldiers" (Cervantes, 88). So astounded were the explorers that they could not find words to express their thoughts, a scene famously captured by the Romantic poet John Keats (1795-1821):

Or like stout Nunez* when with eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific – and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise –

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.*in his original text, Keats confused Hernán Cortés with Balboa

(poetryfoundation.org)

In the breathtakingly arrogant attitude of European explorers of the period, Balboa promptly claimed all lands bordering this new sea for the Spanish Crown. They called the waters the 'Southern Sea' because they had trekked from Darién in that direction. Not living up to its later name, the ocean was beset by storms and so they could not immediately explore the islands they spotted on the horizon (the Pearl Islands).

This great discovery meant that the challenge of finding a sea route to China and easy access to the spices of Asia was back on again. Perhaps there was even a direct sea route that connected the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. A more thorough exploration of the coastline would be needed. Apart from the sightseeing, Balboa got down to the real purpose of the expedition: extracting as much gold and as many pearls as possible from the tribes they encountered over the next few months.

Following Balboa's expedition, new towns were established by the Spanish authorities and encomiendas distributed, that is the legal right to extract forced labour from the indigenous peoples. The discovery of the Pacific Coast opened up the way to further explore by ship the western coast of the American continent. It also convinced Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521) that if he could sail down the Atlantic coast of the Americas far enough he would surely find a way around the continent and into the Pacific, a feat he accomplished in October-November 1520.

As a reward for his discovery, the Spanish Crown awarded Balboa the status of adelantado, which meant he had the legal right to exploit anything he might find in the Pacific Ocean. The catch was he had to fund the expense of any expeditions and give the Crown some 20% of the loot he acquired. Balboa was also awarded the title of Captain-General of Panama and Coiba (a large island off the western coast).

Arrest & Execution

While Balboa had been out exploring, a new governor of Castilla del Oro and its now chief city Darién had been appointed. This was Pedro Arias de Ávila (aka Pedrarias Dávila, b. 1442). Pedrarias was already infamous as a cruel colonial administrator, as indicated by his nickname furor Domini, or 'Wrath of God, but even worse for Balboa, he was a man with a mission. While Balboa had been admiring the Pacific, his old enemy Enciso had not been slow to give his version of the events of his expedition back in 1510 and to press a formal complaint regarding his shoddy treatment. Neither did Balboa's bizarre treatment of Nicuesa please Bishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca (b. 1451), who resided in Spain but was in charge of all military and administrative matters in the empire. The Spanish Crown, considering its powers infringed upon, backed Enciso and dispatched Pedrarias to bring Balboa to justice in April 1513. Fonseca had not forgotten Balboa's claims of "rivers of gold", and he ensured the Crown fully funded Perdrarias' fleet of 23 ships carrying 2,000 settlers, making it the largest expedition to the New World since that of Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) in 1492.

Given that moving a large expedition from Spain across the Atlantic was a very slow process, the issue was made more complex when Balboa's discovery of the Pacific and a new potential source of wealth reached the Spanish king before Pedrarias had reached the Americas. Due to Balboa's new elevated status, Pedrarias now had to tread carefully. At first, friendly relations were forged between the two men, the new governor even promising his daughter in marriage to Balboa (although the girl remained safely in Spain). The next strategy was to send Balboa as far from the centre of power as possible. Consequently, in 1517, he was given the resources to mount another expedition of exploration, this time to the Gulf of San Miguel (eastern Panama).

Meanwhile, Balboa had many supporters, and it became clear that Pedrarias was an unscrupulous administrator only out to line his own pockets. Denouncements were made to the authorities in Spain. The response was to promise a formal review (a residencia) of Pedrarias' term of office so far. Before this could begin, and before Balboa could provide damaging testimony in it, the governor struck to remove his chief rival for Panamanian power and riches. Pedrarias ordered Balboa's arrest in 1519. The charge, a highly dubious one, was treason. Francisco Pizarro was the man selected to bring in Balboa, who was then tried, found guilty, and executed by beheading on 12 January 1519.