Woodes Rogers (1679-1732) was a privateer turned administrator who was instrumental in the fight against piracy in the Caribbean when he served as Governor of the Bahamas (appointed 1717 and again in 1728). Rogers is also known for his three-year privateering voyage around the world (1708-11) and the well-received book which describes it, A Cruising Voyage Round the World.

Woodes Rogers is one of the key figures during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy and was the nemesis of such notorious pirates as Charles Vane, John Rackham ('Calico Jack') and Anne Bonny. Before that, though, Rogers had gained fame for his circumnavigation of the globe where he had captured a fantastically valuable Spanish treasure ship and rescued Alexander Selkirk, the marooned figure who inspired Daniel Defoe’s celebrated novel Robinson Crusoe. In later life, Rogers’ campaign against piracy and his investment in the Bahamas left him bankrupt so that he was obliged to spend several years in a debtor’s prison in England. He returned to serve a second term as governor and spend his final years in the Bahamas.

Early Life & Career

Rogers was born in Poole, England in 1679. His father was a sea captain and the family moved to the bustling port of Bristol around 1697. In 1705, Rogers married Sarah Whetstone, the daughter of Admiral Sir William Whetstone who was based in the Caribbean. Rogers then continued his father’s prospering business sponsoring privateers to attack and loot French vessels in a period when England and France were at war.

The Privateering Circumnavigation

In 1708, Rogers embarked on a privateering voyage himself, one that would ultimately take him around the world. He was perhaps encouraged to embark on such a voyage because the British government had just changed its policy on privateering. In order to encourage privateers even more, the government wavered its 20% cut of any booty taken, satisfied instead with the disruption and economic loss caused to enemies of the state. Rogers was able to organise a consortium of Bristol merchants to put up the initial capital required for the ships and crew in return for a share of the plunder taken on the voyage. Rogers commanded the Duke, a 310-ton frigate while a second, slightly smaller frigate, the Dutchess, was commanded by Stephen Courtney. Rogers’ chief navigator and pilot was the vastly experienced William Dampier (c. 1651-1715) who would finish his career having circled the globe three times.

Rogers left Ireland in September 1708, and he proved to be an able commander. He was tough on himself and his men, with a strict discipline maintained on his voyage (he banned gambling on board, for example, after he discovered many men had gambled away even their clothes). His position as leader, as was not uncommon on such expeditions, was almost immediately tested when some of the crew attempted a mutiny in protest over leaving a neutral ship sail by unharmed. Order was soon restored, and the expedition proceeded. In return for hard work, Rogers’ crews received good food, medical attention, and a generous supply of alcohol.

The privateers plundered French and Spanish ships as they went along, taking on board such precious cargo as gold, gems, and rolls of silk. The first victim was in the Canaries before the expedition had even crossed the Atlantic and rounded Cape Horn to enter the prime target area, the western Pacific.

In February 1709, mid-circumnavigation, Rogers rescued the Scotsman Alexander Selkirk (1676-1721) who had been marooned in the Pacific on the Juan Fernández Islands since 1704. Selkirk's story inspired Daniel Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe. Rogers noted that Selkirk was "clothed in goat skins" and that he "looked wilder than the first owners of them" (Rogozinski, 311).

Not restricted to ships, Rogers also attacked Spanish ports along the Pacific coast such as Guayaquil (Ecuador) in May 1709, where local dignitaries were taken and then released on payment of a ransom. French vessels were also attacked, and Rogers added the Marquis to his fleet of two ships. Rogers sailed to the Galapagos Islands and then, from October, awaited a really big prize off the west coast of America where a fourth ship was added to his fleet, a bark.

The expedition’s richest capture by far was the prize ship Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación Disengaño, a Manila galleon, which carried a huge quantity of Chinese and other precious goods. Taken on New Year’s Day 1710, this was an astonishing coup since only four Manila galleons were ever taken across three centuries of opportunity, so well-armed and protected were these annual Spanish treasure ships that ferried loot between Acapulco in Mexico and Manila in the Philippines. Rogers also tried to capture the Disengaño’s companion treasure ship, the Begoña, a few days later, but his four ships, firing over 500 cannon shots, were still not enough to prevent the Begoña's escape. Rogers had not taken his prize without personal cost for he was hit in the jaw by a musket ball, although this did not prevent him from participating in the battle for the Begoña where he was badly wounded again, this time when a splinter ripped through his left foot. The Disengaño was added to Rogers’ ever-growing fleet but renamed the Batchelor. Selkirk, a useful addition to the crew with his maritime expertise, was given an £800 share of the booty from the Manila galleon and so his was a real rags-to-riches story. On his return to England, Selkirk became an officer in the Royal Navy.

Rogers’ expedition sailed on to Guam in the western Pacific, through Indonesia, across the Indian Ocean, and around the southern tip of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope. The circumnavigators arrived back in England in October 1711, and Rogers sold off his captured ships and their cargoes for an incredible £800,000. The profits of the expedition, the largest of any privateering escapade, were around £170,000 (over £33 million or $45 million today). Rogers, unfortunately, went bankrupt before the proceeds could be distributed, such were the enormous expenses involved in an expedition where all the costs were upfront years in advance of the profits coming back. Rogers at least wrote a popular account of his trip, still regarded as a classic of maritime literature, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, published in 1712.

Governorship of the Bahamas

Over the next three years, Rogers earned his living as the captain of a slave ship which took African slaves to Sumatra. Rogers was known for his tact, diplomatic skills, and sense of humour. He was also a tough and highly experienced mariner and leader of men. In short, he was an ideal candidate for a colonial governorship. The lord-proprietors of the islands of the Bahamas in the Caribbean leased property rights to Rogers for 21 years beginning in 1717. Rogers was appointed the royal Captain-General Governor and Vice-Admiral of the Bahamas in 1717, the first to take up that position. In the rather odd political arrangements of the day, Rogers did not receive a salary, and his income had to be squeezed from taxes on settlers who had established agricultural estates on the islands.

While many governors and officials on the east coast of the American colonies and on the Caribbean islands had turned a blind eye to piracy - either because they were involved in it themselves or because pirate booty was often cheaper than buying goods from legitimate traders - times were changing. By the end of the 1710s, the British government and legitimate merchants were applying pressure on colonial governors to finally stamp out piracy. For this reason, on 5 September 1717, King George I of Great Britain (r. 1714-1727) issued a pardon for pirates willing to give up their hugely disruptive activities. As one report sent to the government by the Council of Trade and Plantations noted in November 1717, piracy in the Bahamas, in particular, was so rife that settlers were abandoning the islands and Britain could well lose them to a foreign power without any permanent population. Rogers was specifically charged with clearing the Bahamas of pirates and given the green light to use any means he saw fit to achieve that goal.

With only three armed ships to use as a stick, Rogers was no doubt glad to receive the juicy carrot of a royal pardon with which he could entice pirates into giving up their lives of crime. New Providence Island, one of the islands in the Bahamas group, had been a notorious pirate haven since 1716 or even before. Not only could pirates accepting the pardon escape the almost inevitable hanging that the majority of their brethren of the coast suffered sooner or later, but they would be given a small plot of land on Providence Island on which to build a home. Pardoned pirates were even given a quantity of free timber to build their new house with.

Some former pirates gained employment in Rogers’ building projects which included repairing the dilapidated fortress, putting up a defensive palisade, and clearing the now-overgrown streets and roads. Others were roped into Rogers’ 400-man militia force that brought order to the islands and manned the fortress. Rogers was busy in other ways to re-establish the colony, forming a council assembly and appointing a chief justice and a secretary general. Cannons were also set up to protect the harbour and ward off any pirates thinking of returning for any other reason than to receive a pardon.

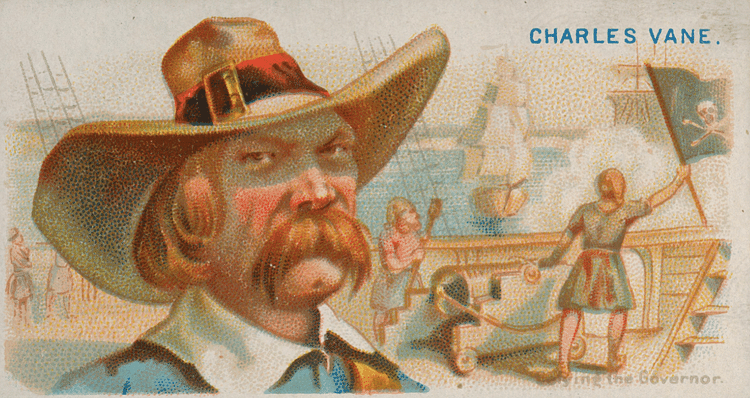

Charles Vane

Rogers’ campaign against piracy started well in 1718 when many pirates did indeed take up the offer of a pardon, but there were still a number of (literally) die-hard villains who did not want to give up their plunder, a condition of the pardon. Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard (d. 1718), sailed north for the Carolinas to continue his pirate raids there. Another villain at large was the English pirate Charles Vane. Escaping the harbour of New Providence, Vane had audaciously sent a fireship towards Governor Rogers’ ship when he was arriving to take up office in July 1718. Vane then fired his cannons at Rogers as he sailed past. Vane’s ship was the super-fast sloop Ranger and so he sailed over the horizon with ease.

Rackham, Bonny & Read

Rogers was canny enough to know that reformed pirates possessed invaluable knowledge of pirate havens and the habits of those captains still at large. The governor, for example, employed James Bonny, husband of the pirate Anne Bonny, as an informant. Anne Bonny had left her husband and joined the crew of John Rackham (aka 'Calico Jack') which also included Mary Read, another infamous female pirate. Rogers issued an arrest warrant for Rackham and his crew in September 1719, although it was a ship sent by the governor of Jamaica that captured Rackham, Bonny, and Read in November 1720.

Captain Hornigold

Unlike Vane, the British pirate Benjamin Hornigold did choose to take up the pardon from Governor Rogers, and he proved another useful ally in Rogers’ hunt for pirates. Captain Hornigold’s first target was Charles Vane, who was still causing all sorts of trouble in the Caribbean and the coast of North America, but his ship proved too fast to pursue. The authorities would eventually catch up with Vane after he was shipwrecked, and he was hanged in 1721 in Port Royal, Jamaica. Hornigold was then tasked with hunting down John Augur (sometimes spelt Auger), a pirate who had recently hijacked three supply ships sailing from New Providence. Augur had just received a pardon but obviously could not resist the allure of piracy. To turn from pirate to pardoned citizen and back to pirate again was the ultimate sin, and Rogers was determined to make an example of Augur. Hornigold commanded one vessel while Captain Cockram sailed another to chase down Augur, who was easily captured after he, too, had been shipwrecked, this time on Long Island.

Augur and a number of other pirates were taken back to New Providence where they were tried for piracy. The trial was used by Rogers to publicly show his determination to catch any and all pirates and bring them to justice. The impressive body of judges consisted of seven commissioners who met in His Majesty’s Guard Room in Nassau on 9 December 1718. With the proceedings led by Rogers himself, the court heard testimony from witnesses and the ten men themselves. All of the men pleaded not guilty despite the overwhelming evidence against them. Nine men were convicted of piracy while one man, John Hipps, was given a reprieve after convincing the court that he had only been with the pirates under duress. The sentence for those found guilty was death by hanging.

By 1719, Rogers had succeeded in clearing out most pirates from the area, although his position was never entirely secure given the lack of practical assistance from London and the fatal effects of tropical disease on his militia force. Indeed, Rogers discovered three islanders were plotting his assassination in 1719, and the trio was publicly flogged. The governor’s position became even more precarious the next year when a fleet of Spanish ships attacked the islands in February but was successfully resisted. There were, too, still some highly dangerous pirates at large, notably Vane.

Later Life & Death

Ironically, the policy of clearing out all the pirates backfired in the case of the Bahamas since, without piracy and the booming trade of pirate loot, the islands became something of a colonial backwater despite the governor’s heavy investments to promote trade as far afield as Mexico. Without any support coming from the British government in London, Rogers eventually ended up bankrupt. From 1721, Rogers was incarcerated in a debtor’s prison in England. Rogers returned to the Bahamas for a second stint as Royal Governor after being reappointed in October 1728, and at least this time he was granted a salary. The colony had fallen back into decline under his successor, Governor Phenney, and Rogers’ return was endorsed by a powerful committee of officials who included several other governors in the North American colonies. Rogers re-established order again, stamped out corruption, and promoted the creation of new plantations growing cotton and sugar cane. Once again, though, without proper funding and with some resistance from the local inhabitants, the Bahamas struggled to free itself from its dark past. Woodes Rogers, after suffering ill health for some time, died in Nassau on 15 July 1732.