The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas (Tordesilhas) was an agreement between the monarchs of Spain and Portugal to divide the world between them into two spheres of influence. The imaginary dividing line ran down the centre of the Atlantic Ocean, leaving the Americas to Spain and West Africa and anything beyond the Cape of Good Hope to Portugal.

The agreement between the two states was fully tested when the Spanish found a maritime route to Asia via the Pacific Ocean, Spain conquered the Aztecs and Incas, Portugal sailed into the Indian Ocean and beyond, and settlements were established in Portuguese Brazil. With this colonial expansion, the two kingdoms squabbled over states and peoples that had never even heard of these two small countries at the end of Europe.

The North Atlantic

The Portuguese started modestly with their empire-building, first colonizing the uninhabited North Atlantic island groups of Madeira from 1420, the Azores from 1439, and Cape Verde from 1462. When the treacherous Cape Bojador was navigated in 1434 by the explorer Gil Eannes, the Portuguese were able to access the trade and resources in West Africa without dealing with Islamic North African traders. The new king, John II of Portugal (r. 1481-1495), pushed for more and so São Tomé and Principe were colonized from 1486. However, yet another island group, the inhabited Canary Islands, were prized by both Spain and Portugal, and the colonial competition heated up considerably.

Prince Henry the Navigator (aka Infante Dom Henrique, 1394-1460) had organised the Portuguese expeditions to explore and develop the North Atlantic islands but his ambitions in the Canaries were repeatedly thwarted. Spanish forces and the indigenous Guanches repelled the Portuguese three times, but the matter remained unsettled. Spain and Portugal were at war between 1474 and 1479, and this period saw a brief occupation of Santiago in the Cape Verde group by Spanish forces. The war came to a close with the peace treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo (1479-80), an agreement which also saw the first attempts to settle which geographical areas should belong to the Spanish and which to the Portuguese. Spain’s claim over the Canaries was recognised, as was Portugal’s over Madeira, the Azores, Cape Verde, and all trade in West Africa.

The Americas

In the final years of the 15th century, the world suddenly became a whole lot bigger for Europeans. The first step was made in 1488 by the Portuguese mariner Bartolomeu Dias who sailed down the coast of West Africa and made the first voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, the southern tip of the African continent (now South Africa). In 1492, Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) ’discovered’ the Americas continent blocking what he thought was a maritime route to Asia. Columbus had sailed representing the Spanish Crown, and King Ferdinand II of Spain, king of Aragon (r. 1479-1516), and his wife Queen Isabella I of Castile (r. 1474-1504) were keen to claim this new land for themselves and block out any competition from European rivals. To that end, the Spanish royals petitioned the help of Pope Alexander VI (r. 1492-1503) who, perhaps significantly, was Spanish. The pope obliged and issued a papal bull in 1493 declaring that the world should be divided by an imaginary line running between the north and south pole (as we would describe it today), cutting through an area 100 leagues (around 400 miles) west of the Cape Verde Islands. Everything to the west of this line was Spain’s and everything to the east Portugal’s in terms of colonies now or in the future. There was the important clause that if a new Christian kingdom was discovered, neither country could claim any sovereignty over it.

Neither side was entirely satisfied with the location of the line or the vagueness regarding the future acquisition of undiscovered lands. Diplomats from both sides pushed for a rethink. Spain had the potential riches of the Americas, Portugal the stronger navy. Cartographers and representatives from both Spain and Portugal, along with a papal envoy to act as mediator, met to discuss what to do next. The location for the meeting was a small town in northwest Spain: Tordesillas.

The Terms of the Treaty

The Treaty of Tordesillas was signed on 7 June 1494. Essentially, the decision of Pope Alexander’s bull was maintained, but the line of demarcation was shifted a little westwards. To be precise, the line moved to 370 leagues west of Cape Verde, approximately 46 degrees 30’ West. This meant the line ran down the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, roughly equidistant between the Cape Verde islands and the West Indies, but it was an approximate and entirely imaginary line as cartographers at the time had no means of measuring longitude. This meant that in practical terms, when actually at sea, mariners could not say for sure if they had crossed the line. Another complication was that the treaty did not specifically specify where the line stopped. Did it go all around the globe to the soon-to-be-discovered Pacific Ocean? Nor did the line consider practical geographical matters such as coastlines, lakes or mountains, and certainly local populations and their own tribal or political borders were not considered at all.

Despite its vagueness, the treaty did at least set out approximate spheres of influence. These included North Africa where the two kingdoms essentially agreed which part of the Muslim-held coast they would attack. The Portuguese were given free rein west and south of Melilla in Morocco while Spain set its sights on Melilla itself and the stretch of the North African coast opposite the Canaries.

Another important clause in the treaty permitted either country’s ships to sail across waters in the other’s jurisdiction if the intention was to gain access to lands under their own control. In this strict sense, the seas themselves remained free. The treaty, then, kept both sides from going to war over territories, at least for the moment. Essentially, Spain had the Americas and Portugal the western coast of Africa and whatever may lie to the east of the Cape of Good Hope, a part of the globe then unknown to Europeans. It was not important to these two royal houses that people already lived in these places or that a highly successful trade network had long been established there.

Global Empires

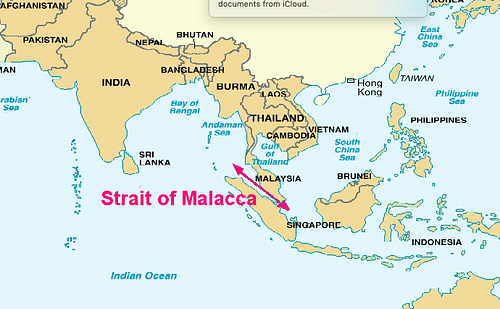

When in 1498 the explorer Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean, suddenly the Portuguese gained access to a whole new trade network involving Africans, Indians, and Arabs. Da Gama pushed on to India where Portugal established several colonies from where further colonizing expeditions sailed east to Indonesia and Japan.

In 1519-22, the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521), then in the service of Spain, sailed around the southern tip of South America and pioneered a maritime route across the Pacific Ocean and on to East Asia. The expedition eventually circumnavigated the globe, but it was access to the spice trade that was crucial. Now Spain became a rival to Portugal in this lucrative trade. The source of many spices was the Maluku Islands or the Moluccas in what is today Indonesia. Not for nothing were these islands simply called the Spice Islands. Spanish and Portuguese navigators and cartographers debated as to where exactly the islands were located on the map: in Portugal or Spain’s sphere of influence according to the Treaty of Tordesillas? There were even accusations that cartographers were deliberately misplacing islands on maps, either to keep their location secret or to support the idea that their country had a rightful claim over them. Magellan had believed the Spice Islands were in the Spanish sphere and had won royal backing for his expedition on those grounds. As it turned out, Magellan was wrong, but Portugal did pay Spain a large quantity of gold to maintain control of the islands. Another area of contention was the lower half of South America, particularly the River plate where both kingdoms laid a claim based on the inexactitude of the line of the demarcation of Tordesillas.

In 1521 Hernán Cortés led a force of conquistadores which attacked the Aztec Empire in Mexico and claimed it for Spain. In 1533 Francisco Pizarro led a force which attacked the Inca Empire in South America, bringing about its eventual collapse. Suddenly, the Spanish had control of two massive empires and all their riches. Meanwhile, in 1532, the Portuguese began to colonize Brazil, which fortunately for them, juts out from the continent in such a way as to cross the line set out by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Meanwhile, the 1529 treaty of Zaragoça (Saragosa) extended the dividing line of Tordesillas to the other side of the globe, confirming Portugal's claim over the Spice Islands while Spain was given the Philippines (even if they were in Portugal’s sphere).

The two spheres of influence had become truly global but so, too, had the colonial competition. The Far East contained powerful states who themselves were keen to either colonise or control trade, states like China, Japan, the Marathas in India, and the sultans of Malaysia. Even more dangerous were fellow European states. The Netherlands, Britain, and France had grown to possess powerful navies by the last years of the 16th century, and they attacked and upset the carefully balanced Portuguese-Spanish status quo everywhere in the world throughout the 17th century and beyond. The Treaty of Tordesillas had become a worthless piece of parchment, and now it was ships, cannons, forts and local armies that backed up an empire, not diplomatic agreements and lines on maps.