The Council of the Indies (El Real y Supremo Consejo de las Indias) operated from 1524 to 1834 and was the supreme governing body of the Spanish Empire in the Americas and Spanish East Indies. Reporting directly to the monarch, the Council had tremendous political, military, economic, and judicial powers over colonies and officials in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Foundation

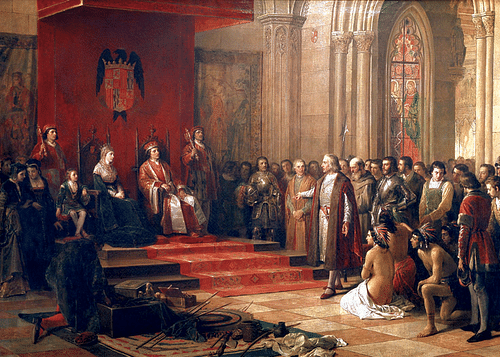

The Council of the Indies was created in August 1524 in response to the ever-increasing territorial gains the Spanish Crown was making in the Americas. At the end of the 15th century, the Spanish monarchy had repurposed the medieval adelantado office, which was now given to adventurers able to fund expeditions in the name of the Crown. The adelantado could keep 80% of the resources they acquired, and the Crown got the other 20%. Under this system, Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) had discovered the New World. The Spanish had then proceeded to colonize the island of Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic/Haiti) in 1494, Puerto Rico in 1508, Jamaica in 1509, and Cuba in 1511. In the spring of 1513, Juan Ponce de León (1474-1521) was the first European to make a documented landing in Florida. Also in 1513, Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475-1519) had crossed the Isthmus of Panama and so became the first European to sight the Pacific Ocean. In the 1520s, the Spanish colonialization process went up another gear or two. Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar (1465-1524), the Governor of Cuba, sent Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) to conquer the Aztecs in Mexico in 1521. Then Pedro de Alvarado (c. 1485-1541) led the brutal conquest of the Maya in Guatemala in 1524.

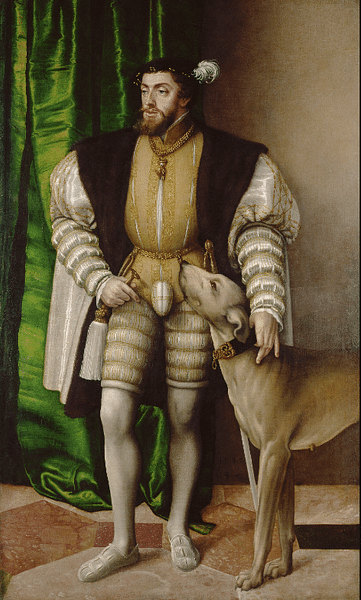

With all these adventurers setting themselves up as local governors and with ever-more settlers arriving from Spain to form more established colonies, the Spanish government needed some means to keep their hands on the reins of power in the New World. The short-term answer was created by Isabella I of Castille (r. 1474-1504) when, in 1493, she appointed Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca (b. 1451) – a royal chaplain and archbishop of Burgos – to keep tabs on what everyone was up to on the other side of the Atlantic. Fonseca filled his challenging role admirably, and this was the system of oversight used until his death in 1524. By then the Spanish Crown was being worn by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556), and he realised this was a bigger job than a single individual could manage. What was needed was an institution with formal powers of governance. Consequently, the Council of the Indies was created, the Americas then being known as the 'Spanish Indies'. This proved to be a wise decision as the empire was about to expand significantly. Francisco Pizarro (1478-1541) made the first moves in the conquest of the Inca civilization in South America in 1533, and Hernando de Soto (c. 1500-1542) began exploring North America as far as the Mississippi River in 1539-42.

Membership & Powers

The Council of the Indies was the supreme legislative and judicial governing body of the Spanish Empire in the Americas. The only authority above the council was the monarchy itself. Its members were few, between six and ten, all appointed by the monarch. The Council had its own independent and efficient postal service linking its various bureaucratic offices and the monarchy. Indicating that evangelism remained an important element of Spanish foreign policy, the first president of the Council was Fray García de Loaísa, the general of the Dominicans and bishop of El Burgo de Osma. Also indicative of the type of individuals who made up the council, Loaísa's colleagues included Pietro Martire d'Anghiera, the Italian humanist, and Luis Cabeza de Vaca, bishop of the Canary Islands.

The Council of the Indies drew up legislation for the Americas colonies, scrutinised and approved the expenditures of colonial officials, gave permission to conduct wars and generally supervised military matters, inspected expedition ships, collected import and export duties, interviewed potential expedition leaders and heard their reports in person on their return, set down the geographical scope of expeditions, and heard appeal cases from the colonial audiencias (the local councils of the larger towns and cities). The Council made colonial and ecclesiastical appointments, including (in consultation with the monarch) the viceroys who typically served for three to five years. The Council could impose on any offenders of government rules and regulations fines, confiscations of property, and prison sentences. It also stepped in to resolve disputes between conquistadors and colonial governors.

Despite all of these powers, the Council of the Indies did face the practical problem that it was thousands of miles from its colonies. The enforcement of the decisions and rulings of the Council in the Americas was not always effective since the number of officials in the field was far too few and communication and transport networks were irregular and unreliable. The level of administrative control over a specific territory varied greatly depending on the abilities, resources, and military strength the governors possessed and the level of local resistance. This was a situation which only worsened as the empire expanded even further.

There were, too, internal divisions over how to proceed with colonialization, particularly which should take precedence: material gain or the conversion of local peoples to Christianity. Some members of the Council were genuinely concerned for the welfare of local people, and they were keen to ensure their exploitation was not unlimited. These concerns were, for example, discussed in a meeting of the Council in 1540. The members were urged by President Loaísa to consider the following six questions:

- How should those who had treated Indians badly be punished?

- How could Indians best be instructed in Christianity?

- How could it be guaranteed that Indians would be well treated?

- Was it necessary for a Christian to take into account the welfare of slaves?

- What should be done to ensure that governors and other officials carry out the government's orders to be just?

- How could the administration of justice be properly organised?

(Thomas, 474-5)

Finally, two persistent accusations aimed against the Council of the Indies were the slowness with which decisions were made and the integrity of its members. Corruption was not unknown, particularly as council members wielded such tremendous power and that they could award themselves sinecures and benefits in the territories colonized. Some perceived corruption was undoubtedly down to mere incompetence - to get the belongings of a Spaniard who had died in the Americas back to Spain, for example, seemed a task beyond the administrators on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Casa de Contratación

The council included the Casa de Contratación de las Indias, a House of Trade actually created in January 1503 by Fonseca. The Casa, based in Seville (and then Cadiz from 1717), was essentially responsible for all matters of trade in the American colonies, acting as the sole clearing house and supervising the fleets that sailed back and forth across the Atlantic. It functioned as "a market, a registry of ships and captains, a magistracy, and a centre of information" (Cervantes, 64). There was also a navigational school to train the captains and pilots, which were always in short supply.

The Casa de Contratación appointed an official for every ship bound for the Americas who had the responsibility to inspect crews, cargoes, and passengers and to record everything that went on aboard and at port. Another duty of the Casa de Contratación was to organise all the invaluable knowledge that colonial administrators sent back to Spain, such as maps, notes on local resources, and descriptions of local peoples. With the creation of the Council of the Indies, the Casa de Contratación was given additional responsibilities, which included acting as an advisory board for colonial appointments, both civil and church-related.

Diminishing Powers & Closure

The idea that a single centralised body could govern a huge swathe of the Spanish Empire became untenable by the end of the 17th century. As the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714) came to a close, Philip V of Spain (r. 1700-1746) replaced the Casa de Contratación with the Ministry of the Marine and the Indies. In 1714, the military responsibilities of the Council of the Indies were transferred to the newly-formed Ministry of the Navy and the Indies.

Then, in 1789-90, the Council of the Indies was largely (but not completely) closed down, and its various responsibilities were distributed across several ministry departments within the government. The Council continued to function as an advisory board, but even this capacity was removed in 1812 before being reinstated in 1814. Finally, in 1834, the Council of the Indies was definitively abolished.