The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto (c. 1500-1542) landed on the west coast of Florida on 30 May 1539, hoping to find wealthy kingdoms to conquer and plunder. His crew journeyed for over four years in southeastern North America, savaging the local peoples, but ultimately returned home empty-handed. They found the region to be filled with dozens of strong agricultural societies, but there were no rich, glittering states to vanquish.

Hernando de Soto

Born in Jerez de los Caballeros in Estremadura, Spain, Hernando Mendez de Soto was the second son of wealthy parents. Since his older brother would inherit the family estate, he had to establish his own career. At the age of 14, de Soto went to Central America as a page for the first governor of Panama, Pedrarias Dávila. As Dávila's representative, he explored Costa Rica and Honduras in search of treasure and land. He conquered Nicaragua in 1524 and was made the alcade, or mayor, of León. In 1530, de Soto signed onto Francisco Pizarro's (1478-1541) expedition to Peru. He would play an important role in the conquering of the Inca and would receive the third largest portion of the stolen wealth, after Francisco Pizarro and his brother Hernando. De Soto was the first European to enter Cuzco, the capital of the Inca Empire.

Now a very rich man, de Soto returned home in 1536 and married Isabel de Bobadilla, daughter of Dávila. Despite having a new wife and a fine home in Spain, de Soto grew restless. He wanted to be a governor like Pizarro. In 1537, King Charles I of Spain (aka Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor) granted de Soto an asiento to invade and settle La Florida. De Soto was given four years to conquer the 'Indios' and to select 200 leagues of coast for his personal domain.

Explorations in Florida

There had been two previous explorations of Florida. In 1513, Juan Ponce de León (1460-1521) had led the first one, landing along Florida's east coast, he charted the Atlantic coast down to the Florida Keys and north along the Gulf coast. He left Florida in 1514, briefly returned to Puerto Rico, and then headed back to Spain. The second expedition was led by Pánfilo de Narvaez (c. 1470-1528) in 1527 to establish settlements and garrisons in Florida. This mission failed miserably. De Narvaez himself died in 1528, and only four members of his party of 600 ever returned. The four made it home to New Spain after being held captive by Amerindians and wandering through the Southwestern US and northern Mexico for eight years.

De Soto's Journey

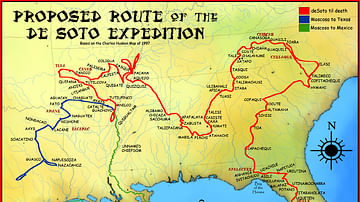

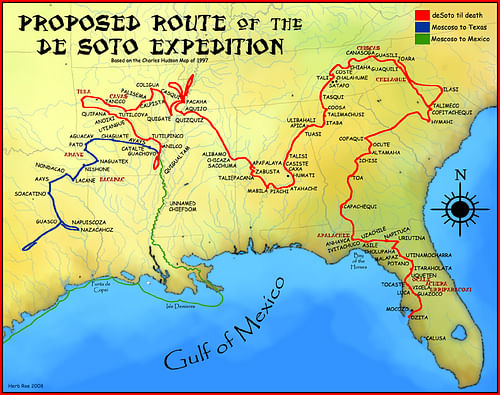

On April 7, 1538, de Soto and 650 men set sail from Seville, Spain, to La Habana Cuba, and they departed from there in May 1539 for Florida. The expedition included knights, foot soldiers, artisans, priests, boatwrights, and scribes, as well as 200 horses and a large herd of pigs. De Soto landed on the west coast of Florida at the Amerindian chiefdom of Ocita, probably in the Tampa Bay area. During the next few months, the expedition explored the area around their landing, then traveled north and northwest to Anhayca, the principal town of the indigenous Apalachee chiefdom located around Tallahassee.

This early exploration set the pattern for the whole de Soto mission. At that time, the southeastern US was filled with many different chiefdoms of farmers. De Soto traveled from one indigenous community to another following local trails and camped near villages where stores of maize could be found. There he would demand that the local leaders tell him where he could find gold, silver, or any other precious objects. De Soto carried no food supplies other than the pigs (which he rarely slaughtered), and his army fed itself on maize taken from villagers, often putting them at risk of starvation. He also seized dozens of local men, women, and children to carry equipment and supplies, perform camp chores, and satisfy any other needs the army might have. Any resistance brought swift and cruel punishment.

On one of their early forays from Ocita to explore the countryside, de Soto's army encountered a Spaniard, Juan Ortiz, who had been part of the Narvaez expedition and had been held captive by the Apalachee for about ten years. Ortiz provided de Soto with intelligence about the area around Tampa Bay and would serve in a critical role as a translator.

De Soto and his men spent the winter of 1539-1540 in Anhayca and several nearby settlements. Here they took a hundred captives, put them in chains with collars around their necks, and required them to carry baggage and grind maize to feed the army. In the spring, the explorers headed north into Georgia with their slaves and meandered through South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee, before heading southwest through the northwestern corner of Georgia into central Alabama. There they encountered the heavily palisaded town of Mabila where they were attacked by warriors of Chief Tuskaloosa (also given as Tuscaluza and Tuscaloosa). A fierce, day-long battle ensued in which 22 Spaniards were killed and 148 were wounded; however, the Amerindians took the brunt of the battle losing 2,500 to 3,000 men.

The expedition remained in Mabila for about a month to recover from its wounds. De Soto and his army then traveled on to the lands of the Chickasaw, where they encamped for the winter of 1540-41. On the way, they came in contact with several other indigenous groups including the Ichisi, Ocute, Cofitachequi, Coosa, and Tuscaluza. These groups were all chiefdoms, mostly classless societies with a chief who made the major decisions. All built towering earth mounds for ceremonial activities and farmed maize on river bottomlands.

De Soto and his army spent a difficult winter at Chickasaw. The winter of 1540-41 was bitterly cold, they did not have adequate shelter, and their clothing was threadbare and in short supply. The Chickasaws also kept them constantly on edge by waging guerilla warfare against them, day and night. Relations turned particularly sour when de Soto prepared to leave in the spring and demanded 200 burden-bearers to serve them in their travels. Just before dawn on March 4, the day the expedition planned to depart, several hundred Chickasaws attacked the Spanish and set fire to their camp. Twelve Spaniards, 59 horses, and hundreds of pigs died in the attack. The number of Chickasaws lost is not known.

After taking some time to recover, the expedition moved out in a northwesterly direction through the chiefdoms of Alibamu and Quizquiz, and along the way discovered the Mississippi River. Here they built rafts to cross the mighty river, and while crossing, they were greeted by people from the chiefdom of Aquixo. They arrived in a fleet of 200 canoes, each carrying a hundred warriors decorated with colorful paints and feathers. Their leader presented de Soto with a gift of fish and plum loaves and claimed to represent the chief of Pacaha, whose province lay farther up the river. De Soto rebuffed this attempt at friendship by ordering his crossbowmen to fire upon the visitors, forcing them to withdraw but not without gestures of disdain.

After crossing the river, de Soto and the expedition traveled through central Arkansas and met the chiefdoms of Casqui, Pacaha, Quiguate, Coligua, Cayas, and Tula. In this region, they entered the territorial fringes of the Great Plains where the local people were buffalo hunters. The Casqui were very welcoming and gave the Spaniards food and buffalo hides as gifts, even though they had been suffering under a prolonged drought. The Chief of Casqui also offered de Soto his daughter to wed, saying that his greatest desire was to unite his blood with that of so great a leader as he. When the Casqui were told by the expedition's priests about their Christian God, the chief pleaded with them to pray for rain. De Soto had a large cross erected on their temple mound, and the priests conducted a religious ceremony. Incredibly, it rained the following day. The emboldened Casqui then asked the Spaniards to join them in an attack on the rival Pacahas chiefdom, claiming they possessed gold. A combined force of Spanish soldiers and Casqui warriors routed Pacaha's main town, but the Spanish found no gold.

De Soto and his army continued their travels and arrived in early November at Autiamque located on the south side of the Arkansas River between Little Rock and Pine Bluff. Here they spent another bitterly cold winter, during which they were completely snowbound for a month. By now 250 of his men were dead, and 150 horses had died. Their interpreter Juan Ortiz also died that winter, and from this point on their communication with the indigenous peoples became extremely difficult.

The expedition set out from Autiamque in early March 1542 and traveled to the chiefdom of Anilco, located along the Arkansas River just above its confluence with the Mississippi. Anilco was one of the most densely populated chiefdoms encountered by de Soto on his trip. Growing increasingly frustrated at the condition of his army and its failure to find gold, de Soto sent a message to the local chief, demanding that he appear and offer tribute. When the chief refused, de Soto flew into a rage and ordered a brutal attack, slaughtering hundreds of men, women, and children.

Just before the attack, de Soto fell ill with a fever and was unable to lead it. He died a few days later at the age of 42 and Luis Moscoso de Alvarado succeeded him as captain-general. Wishing to conceal de Soto's death from the Amerindians, as they had been led to believe he was immortal, the Spaniards wrapped de Soto's body in shawls weighted down with sand, and under the cover of darkness, sunk it in the Mississippi River.

The Expedition Returns

After de Soto's death, the remaining members of the expedition debated on how to get to New Spain (Mexico) and end the mission. They could escape by either land or river. They first chose the land route but soon abandoned this approach as they had difficulty finding enough corn to sustain themselves along the trail. They went back to the Mississippi and choose as their jumping-off point Aminoya where there were two palisaded towns. One of these they moved into, and the other they tore down to build their ships.

On the morning of 2 July, they started down the river. In addition to the current, each boat was propelled by seven pairs of oars and a sail that unfurled when the wind was right. Their progress was rapid, and they went 48 miles on the first day before mooring for the night near the mouth of the Arkansas River.

The next day, they came to Huhasene, under the domain of the chieftain Quigualtam, and expropriated a large supply of corn from the granaries of his village. This infuriated the chief, and the following morning he attacked the Spanish with a fleet of a hundred large war canoes. The warriors continued the attack all that day and throughout the night, with the Spaniards fleeing down the river as fast as they could. Finally, around noon on 5 July, Quigualtam ordered the canoes to head back home, as they had apparently reached the end of their territory. No sooner had this attack ended that another chief sent a second fleet of 50 large canoes to confront them. This chase lasted another day and night until these combatants also disengaged.

At this point, now near the present-day city of Natchez, the Spanish were finally left alone, probably because they were no longer passing along the territory of any more powerful chiefdoms. Moscoso and his men reached the mouth of the Mississippi River 12 days later, having traveled 400-500 river miles. From there they sailed and rowed along the Gulf Coast, and 53 days later on 10 September 1543, they arrived at the mouth of the Panuco River in Mexico, where there was a Spanish settlement. Here the de Soto expedition ended after four years and four months, with about half the army surviving. The explorers had walked, ridden, and sailed for well over 8.000 kilometers (5,000 mi).

Significance of De Soto Expedition

At the time, the de Soto expedition was considered a failure, since they did not find a state-level society with stores of precious metals and gems like those possessed by the Inca Empire and the Aztec civilization. The Spanish interest in the region waned, and it was left to France and England in the mid-17th century to pursue imperial designs in the region. Regardless, the de Soto expedition was successful in many ways. Subsequent expeditions into the southeastern interior during the latter half of the 16th century and beyond relied heavily on the knowledge generated by this expedition.

It was the De Soto expedition that first succeeded in penetrating and exploring the vast interior areas of southeastern United States. As the first Europeans to see the interior of the continent, the De Soto expedition is comparable in significance to the Coronado Expedition (1540-42) which explored the western United States. Written accounts of the journey contain the only descriptions of the people who inhabited the region prior to European contact. Further, expedition reports about the land later helped stimulate colonization. (De Soto Trail, 14)

The de Soto expedition is also historically important because the participants observed and left a record of many indigenous societies while they were still intact. These societies had built large mound centers and were expert horticulturalists growing maize, beans, and squash in quantities sufficient to sustain sizeable populations. However, these societies were beginning to struggle, troubled by internal instability and external competition, and were starting to fracture and recombine. Their population numbers were also greatly decimated by the diseases brought onto them by the long, extensive de Soto expedition.

When Europeans again began exploring the southeastern interior in the late 17th century, they found that many of the large chiefdoms had collapsed, the mound-building societies had mostly disappeared, and the survivors had begun coalescing themselves into the historic groups of the 18th century which included the Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Cherokees, and Catawbas.