The Viking Age (c. 790-1100 CE) transformed every aspect of the cultures the Norse came in contact with. The Vikings usually struck without warning and, in the early years, left with their plunder and slaves to be sold as quickly as they had come. In time, they began to colonize the regions they attacked but, whether it was a quick raid for profit or a long-term campaign for land and power, every military operation was organized and led by a skilled warrior.

There are many great Viking leaders recorded during the Viking Age but a number of them stand out either for the impact they had on their time or the values their stories embodied. Freydis Eriksdottir, for example, is not a well-known Viking leader but, in one story at least, she epitomizes Viking courage and the warrior ethos. Although many names could be included in a list of great Viking leaders, the twelve most notable are:

- Ragnar Lothbrok – c. 9th century CE

- Ivar the Boneless – c. 865-870 CE

- Rollo of Normandy – r. 911-927 CE

- Erik the Red – c. 950-c.1003 CE

- Leif Erikson – c. 970-c.1024 CE

- Freydis Eriksdottir – c. 970-c.1005

- Hastein (also known as Hasting) – 9th century CE

- Harald Fairhair – r. c. 872-933 CE

- Harold Bluetooth – r. 958-985 CE

- Sweyn Forkbeard – r. 986-1014 CE

- Cnut the Great – r. 1016-1035 CE

- Harald Hardrada – r. 1046-1066 CE

Not all of these figures are completely historical and, among those who are, not all of their stories can be authenticated. History and myth weave throughout the narratives of most of the above but, whether historical or legendary, these leaders made a lasting impression on the world.

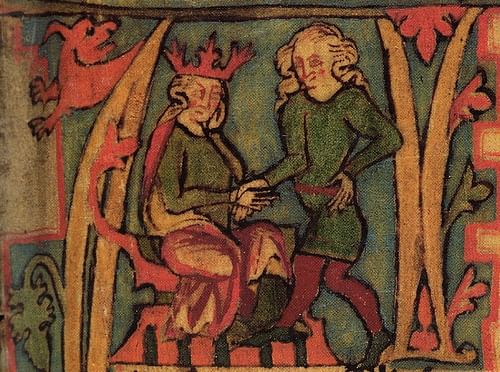

Ragnar Lothbrok

Ragnar Lothbrok is the hero of the epic The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok and is considered an amalgam of a number of Viking chieftains. He is regularly cited in scholarly works as an actual historical figure but, at the same time, these authors concede he is most likely a fictional character, perhaps modeled most closely on the Viking leader Reginherus. Ragnar fought dragons and attempted to conquer Britain in only two ships while the historical Reginherus is known only for the 845 CE raid on Paris when he was paid by Charles the Bald (r. 843-877 CE) to leave the city alone (thus setting the precedent for large payments to Viking chiefs for protection).

Ragnar is also known, however, from the Ragnarsdrápa, a 9th century CE poem by the bard Bragi Boddason (also known as Bragi enn gamli), which is a shield-poem (a work describing mythological or legendary images carved on a shield). Allegedly, the shield was given to Bragi by someone named Ragnar, and it is another Old Norse poem that identifies this Ragnar with Ragnar Lothbrok. However, it may just as well refer to another Ragnar instead, and because Lothbrok's historicity is doubtful, this does not speak in favour of him being historically connected with this shield-poem.

According to The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, Ragnar was warned by his psychic wife Aslaug against using only two ships to conquer Britain. He ignored her warning, was captured by King Ælla of Northumbria (d. 867 CE), and executed by being thrown into a pit of snakes.

Ivar the Boneless

Ivar is allegedly the son of Ragnar Lothbrok and is best known from the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, the Tale of Ragnar's Sons, and the Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus (c. 1160-c. 1220 CE). He is also often equated with one of the leaders of the Great Heathen Army (named 'Hingwar' in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) that invaded Britain in 865 CE and it is conceivable that the legendary Ivar may have indeed been inspired by this Hingwar. Whether Ivar existed one-on-one as he is depicted in the sagas is still debated in the present day, however.

In the Tale of Ragnar's Sons, he sails to Britain with his brothers to avenge their father's death but refuses to fight with them against King Ælla. Afterwards he makes a deal with the king for land but Ælla stipulates he can only have as much ground as he can cover with a bull's hide. Ivar cuts the bull's hide into strips and encircles the area which will become the city of York. This story, of course, is borrowed from the much older tale concerning Dido of Carthage who does the same thing with an ox-hide to found her city in North Africa.

After founding York, Ivar avenges his father's death by killing King Ælla through the mysterious torture known as the blood-eagle and then rules Northumbria from York. Only very scarce and often contradictory sources place him at the head of the Great Heathen Army and credit him with killing King Ælla at the Battle of York in 867 CE. Whether he was an actual historical figure, Ivar the Boneless came to epitomize Viking ruthlessness and cunning.

Rollo of Normandy

Rollo is the founder of Normandy who had previously led raids in the Kingdom of West Francia. Rollo is thought to have been involved in the Siege of Paris in 885-886 CE when the city was defended by Odo of West Francia (l. c. 856-898 CE). After the siege, which only ended when Charles the Fat followed the earlier precedent and paid the Vikings to leave, Rollo remained in the region raiding various settlements. In c. 911 CE, Charles the Simple (r. 893-923 CE) was tempted to follow that same precedent but, instead, offered Rollo land and the hand of his daughter Gisla in marriage in return for his loyalty and protection from Viking raids.

Rollo accepted the king's offer and founded the region of Normandy (“land of the Norsemen”). He remained true to his pact with Charles the Simple and not only defended West Francia from the Vikings but improved the lives of the people in his realm. He revised the laws, restored churches and abbeys, and fought for the king personally against threats to his rule. His personal achievements aside, he is also famous as the great-great-great-grandfather of William the Conqueror.

Erik the Red

Erik the Red (also known as Erik Thorvaldsson) was an Icelandic explorer who became the first to settle Greenland. His story is told in The Saga of the Greenlanders and Erik the Red's Saga although these accounts differ on a number of points. Basically, Erik was outlawed for killing a man in Iceland (just as his father, Thorvald Asvaldsson, had been exiled from Norway for the same crime and had come to Iceland with his son) and was banished for three years. He had heard of a land to the west where earlier Norse sailors had attempted settlements and sailed there, exploring the area throughout the three years of his exile.

When he returned to Iceland, he told everyone about the wonderful place he had discovered and called it Greenland in an effort to entice more people to come. The sagas relate how he consciously pitched the name to the Icelanders in the hopes that a pleasing name would result in more settlers. This pitch was successful and he returned to Greenland with 14 ships and established colonies, thus founding Greenland.

Leif Erikson

Leif, the son of Erik the Red, is credited with landing ships in North America some 500 years before the infamous “discovery” of the New World by Christopher Columbus. As with his father, Leif's story comes from The Saga of the Greenlanders and Erik the Red's Saga. According to these accounts, Leif embarked on a series of sea ventures, one of which brought him into contact with King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway (r. 995-1000 CE) who had forcibly converted the country to Christianity. Leif swore fealty to Olaf and was returning to Greenland to evangelize the people when he was blown off course and wound up in a strange place he would call Vinland (“vine-land” for the grapes found there) known today as Newfoundland, Canada.

The Vikings built a settlement at the northernmost point of a peninsula in the area now known as L'Anse aux Meadows and the small community commenced a seemingly lucrative trade with their friends and relations back in Greenland. The natives of the land, however, were not so pleased with the new arrivals and this, along with the difficulties of sea-travel to and from Greenland, finally led to them abandoning the settlement. Leif eventually returned to Greenland where he allegedly fulfilled his promise to Olaf in converting the populace to Christianity although, by this time, most of them were probably Christian already.

Freydis Eriksdottir

Freydis was either the sister or half-sister of Leif Erikson, and the daughter of Erik the Red. Her reputation as a great Viking leader is contested because of two very different accounts of her behavior in the New World, virtually all that is known of her. The first account comes from Erik the Red's Saga in which she is depicted as a brave warrior woman who, left alone by the retreating men of her party, drives off the heavily armed native tribe that attacked the settlement with only a sword; the second comes from The Saga of the Greenlanders in which she is a conniving woman who orchestrates the murder of her business partners by her husband and his men and then, when they refuse to kill the partners' women, does so herself with an axe.

There is no verifying which of these accounts is true but it is thought that The Saga of the Greenlanders – which is the later of the two – purposefully spun the tale of Freydis in the New World to make her look bad. The image of the courageous Viking warrior woman facing down a hostile enemy alone with her sword was not in line with the Christian ideal of women and, as can be seen elsewhere (such as the biblical tale of Jezebel or the historical Cwenthryth of Mercia), strong women who did not fit the Christian narrative were turned into villainesses.

Hastein

Hastein (frequently referenced as Hasting) is thought to have been historical but, because his name is referenced so often without any qualifiers, it is difficult to know whether it is the same person mentioned in each story. He is placed in the Mediterranean with Bjorn Ironside in c. 859 CE, in West Francia with the same c. 858 CE, as part of the Great Heathen Army of 865 CE, and as part of the invading force of Mercia in 892 CE. Part of the problem in ascertaining what he did or did not do is the semi-legendary status of Bjorn Ironside with whom he is closely identified.

Hastein is thought to have originated the Viking ploy of pretending to convert to Christianity, feigning death, and being carried through the gates of a city only to miraculously revive, kill his would-be benefactors, and open the gates for his men (now famously depicted in the TV series Vikings where Ragnar Lothbrok does this very thing). The first time he is said to have done this was at the city of Luna which was then taken. Historically, he is known to have led the force that invaded Mercia in 892 CE, fighting against Alfred the Great and Aethelred and Aethelflaed of Mercia. He disappears from the historical record in c. 896 CE.

Harald Fairhair

According to the stories from sources such as Harald's Saga and others, Harald Fairhair was the first king of a united Norway. His epithet is closely associated with his rise to power as it is said that he fell in love with the princess Gyda of Hordaland who refused his attentions. He swore he would not cut or tend his hair in any way until he had proven himself worthy of her love by conquering the separate kingdoms of Norway and uniting them under his rule.

Harald's gesture may seem trivial in the modern day but, for the Norse, personal hygiene was an important value and a prince, especially, was expected to care for his hair. In the ten years it took Harald to unite Norway, according to scholar Martin J. Dougherty, he was most likely known as mop-hair but, having succeeded and won both Gyda and his kingdom, he had his hair cut and styled and was known as the fair-haired (176). He was the father of two other great Viking leaders, Haakon the Good (r. 934-961 CE) and Erik Bloodaxe (king of Norway 931-933 CE, king of Northumbria 947-948,952-954 CE) the latter of the two being the last Viking king of an English realm.

Harald Bluetooth

Harald Bluetooth is best known as the Danish king who converted the people of Denmark to Christianity. Christian writers such as Widukind of Corvey (d. c. 973), claim that Harald was converted to Christianity through the miracles shown him by a cleric named Poppa, such miracles including the routine holding of a red-hot iron bar without being burned owing to Poppa's faith. In reality, Harald converted in order to hold off an invasion by the Germans, who were already Christian, and who would have had problems justifying an attack on a Christian kingdom to the church of Rome.

Although his conversion of Denmark is most often cited as his great accomplishment, he was an efficient ruler who improved his country's infrastructure and solidified contracts and treaties with his neighbors. Even so, his conversion did not sit well with his son, Sweyn Forkbeard, who overthrew his father and took power c. 986 CE.

Sweyn Forkbeard

Whether Sweyn was a rogue Christian or a die-hard pagan is unclear but he certainly used the church to his advantage. After taking the throne from his father, he consolidated Denmark's tenuous hold on Norway and became king of both countries. Wary of interference from Germany and the church at Rome, he concentrated his efforts on building the power of the church in Britain. With the armies of Denmark and Norway under his control, Sweyn exercised considerable power in the region and invaded Britain in 1002 CE, allegedly in response to the massacre of a Danish settlement there.

Sweyn continued his military campaigns in Britain through 1013 CE, by which time he had conquered every force sent against him. He was crowned King of England in December 1013 CE, but died only a few weeks later in February of 1014 CE. He was succeeded by his son Harald II who held the throne while his older brother, Cnut, consolidated power in the land. Once Cnut had subdued any opposition, Harald abdicated in his favor.

Cnut the Great

Cnut is known as “the great” because of his skill in every area of kingship. He conquered Britain and united it with Denmark and Norway and then took Sweden. His goal was to unify the disparate people and cultures of these lands under a single rule and, for a time, he succeeded. He revised the laws of Britain and equalized punishments for crimes throughout the diverse territories. As with many, if not most, Viking rulers at this time, it is unclear how seriously he took his conversion to Christianity but, like his father, he knew enough to treat the church well and manipulate the clergy to further his various agendas.

By the time of his death, Cnut was known as the wise king of England, Denmark, Norway, and partly of the Swedes as he was unable to finally hold all of Sweden. He established firm trade contracts and improved the infrastructure of Britain as well as his other realms.

Harald Hardrada

Harald Hardrada is known as the last Norse king of the Viking Age and his death at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 CE as the defining close of that period. Harald's life was an almost constant adventure from a young age. He was wounded at the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030 CE and fought to restore his brother Olaf to the throne of Norway when he was only 15. He then fled Norway for Kievan Rus, served in the famous Varangian Guard in Constantinople, and returned to claim the throne of Norway.

He successfully raided Denmark in traditional Viking style a number of times but was never able to conquer it. Finding himself invited by an envious Northumbrian earl to come claim the throne of England, Harald invaded in 1066 CE and made headway until his death in battle at Stamford Bridge. His major contribution to history was weakening the Anglo-Saxon forces under the king Harold Godwinson to the point where, when William the Conqueror invaded later that year, his victory at the Battle of Hastings was almost assured.

Conclusion

Aside from these leaders, as noted, there were many other great Norse and Viking kings, queens, and warriors. One of the most memorable was Egil Skallagrimsson (c. 910-990 CE), a warrior from the age of seven, according to the sagas, who killed the son of Erik Bloodaxe but saved himself from execution by composing and reciting a poem in the king's honor. The legendary hero Gunnar Hamundarson (c. 10th century CE) also deserves mention as an invincible hero who died protecting his beloved home and who, after death, remained happily as a spirit on the land he had loved.

However one interprets the actions and ethos of the Vikings in the present day, one cannot deny that the Viking Age changed the course of history forever. Each of these leaders, even if their contributions were not well known outside of a small community in their time, influenced the lives of those who came after. There is no doubt of the inspiring effects of the tales of great legendary heroes like Ragnar Lothbrok and his sons but, equally, of the historical Viking leaders who set out to make a name for themselves and changed the world.