Cwenthryth of Mercia (also given as Cwoenthryth, 9th century CE) was the daughter of King Coenwulf (r. 796-821 CE). Little is known of her actual life but she later became infamous in the 12th century CE through the legend of St. Kenelm as the scheming sister who arranges her brother Kenelm's death. There is no historical basis for this legend and the casting of Cwenthryth as villainess was most likely due to the historical Cwenthryth's dispute with Wulfred, Archbishop of Canterbury between c. 805-832 CE, and a later scribe's poor opinion of a woman challenging the authority of the church.

Recent interest in Cwenthryth has been sparked by the character Kwenthryth in the TV series Vikings where she is played by American actress Amy Bailey. The character in the show is actually a combination of three medieval noble women all of whom were demonized by later writers to such a degree that very little – or nothing – remains in historical accounts to contradict the official version of their lives: Cwenthryth of Mercia, Cynethryth of Mercia (died c. 800 CE, wife of King Offa, r. 757-796 CE)), and her daughter Eadburh of Mercia (d. c. 802 CE). The TV character's name is taken from the historical Cwenthryth; her manipulative aspects come from the legend combined with snippets from the other two women's lives.

Historical Cwenthryth

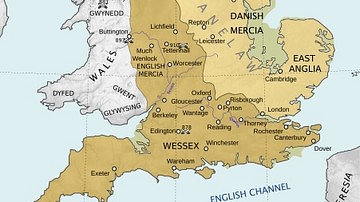

The dispute between the historical Cwenthryth and Wulfred goes back to before she was even born. King Offa of Mercia defeated Eahlmund of Kent (r. 784-785 CE) in battle in 785 CE and took control of the kingdom. Mercia and Kent had a long and contentious relationship prior to this time as Mercia sought control and Kent tried to keep its autonomy. Eahlmund's father, Egbert II (r. 765-c.779 CE), had previously defeated Mercia in 776 CE and Kent retained its independence until Offa's 785 CE offensive.

Once Offa was in control, he made significant changes to a number of institutions and policies and, among these, was to reduce the prestige and power of the archdiocese of Canterbury by creating another archdiocese at Lichfield in 787 CE. According to surviving documents, this was done primarily because of Offa's personal distaste for the Archbishop of Canterbury Jaenberht (presided 765-792 CE) who had supported Egbert II and his son. This feud set the precedent for later problems between Canterbury and the ruling house of Mercia.

Offa was succeeded by his son Ecgfrith (r. 796 CE) who ruled only a few months before dying, most likely assassinated, and Coenwulf, a distant cousin, took the throne. Records and letters from his reign show that Coenwulf experienced multiple problems with Wulfred, Archbishop of Canterbury, over lands Coenwulf owned in the archbishop's diocese, Minster-in-Thanet and Reculver. Wulfred denied the legitimacy of Coenwulf's claims and Coenwulf, of course, contested this in letters to Pope Leo III.

When Coenwulf died in 821 CE, his will stipulated that these lands were left to his daughter Cwenthryth, who was Abbess of the Parish of Minster-in-Thanet. Wulfred reasserted his right to the lands at this time and requested rent from Cwenthryth as well as her official recognition of his lordship. Cwenthryth refused and so Wulfred filed a lawsuit against her to force compliance in c. 824 CE.

At some point between that time and 827 CE, councils were convened to decide the matter but no resolution is recorded. Wulfred then sued Cwenthryth again, this time for compensation for loss of income from the properties and, in 827 CE, Cwenthryth is said to have retired to the Abbey at Winchcombe, which had friendly relations with her father, and there is no further record of her; Wulfred acquired her properties in accordance with his second lawsuit. The account of her legal battle with Wulfred, and her position of abbess at Minster-in-Thanet, is literally all that is known of the historical princess Cwenthryth.

Cwenthryth in Legend

In the 12th century, a scribe at Winchcombe wrote The Story of St. Kenelm the Little King which would transform Cwenthryth into the medieval villainess she would be known as ever after.

The story goes that, when Coenwulf died, he left his kingdom to his seven-year-old son Kenelm who was loved by the nobles of Mercia and welcomed as their king. Kenelm was tutored by a noble named Aesceberht who was the lover of Kenelm's older sister Cwenthryth. Cwenthryth suggested to Aesceberht that, if Kenelm were killed, she would be made queen and he would rule with her.

Aesceberht invited young Kenelm on a hunting trip during which Kenelm is said to have known Aesceberht's intentions but trusted in his god's will for his life. Aesceberht led Kenelm further and further into the woods and then killed him by chopping off his head; afterwards he buried him in a thicket.

At the hour of Kenelm's death a number of devout clergymen were praying in the Church of St. Peter in Rome when a white dove flew in through a window and landed on the altar, gripping a letter in its claws. The men took the letter from the bird but could not read it because it was not written in Latin. There was one among them, though, who knew the “English tongue” and translated the letter for the rest of them and then for the Pope.

The letter was an account of how the little king Kenelm had been killed and buried in the woods and the Pope then wrote to all the kings of Britain telling them what had happened and commanding them to go find the boy's body and give it a proper burial. The kings obeyed, found Kenelm's grave, and carried the body toward Winchcombe to be buried “for they deemed that Kenelm was a holy child and they knew that he had been wickedly slain by the guile of his sister Cwenthryth” (Freeman, 88).

Cwenthryth was at the Abbey at Winchcombe as the procession came into town with Kenelm's body when suddenly all the bells began ringing without anyone near the ropes. Cwenthryth was reading from her psalter when this happened and asked her attendants what it meant. When she was told that her brother's body had been found and was proceeding toward the abbey, she said, “Should that be true, may my eyes fall out upon this book” and, in that very moment, her eyes fell out of her head onto the pages of the psalter. She and Aesceberht soon after “died wretchedly”, though no details are given, and Kenelm was given a Christian burial. Over his grave they built St. Kenelm's Chapel which, the story claims, one can visit at the time of the author's writing.

Another version of the story includes a cow or white cow who, after Kenelm is murdered, comes and sits on his grave day and night for years to draw attention to the crime. In this version, the white dove takes somewhat longer to make its flight to Rome but the rest of the story proceeds along the same lines as the Winchcombe account. Commenting on the Kenelm legends, scholar Edward Augustus Freeman writes:

It is hard to see what should have made anybody invent such a tale if nothing of the kind had ever happened. Yet it is a very unlikely story. For it was not the custom of the English then to choose either children or women to reign over them so that, if Coenwulf left only a daughter and a young son, it is next to certain that his brother Ceolwulf would have been chosen king (87).

However unlikely the tale may seem to a modern audience, it was accepted – as it seems all the tales of the Christian saints' lives and miracles were – as fact by audiences of the time it was written. By the time of Geoffrey Chaucer (c.1343-1400 CE) pilgrimages to the site of St. Kenelm's Church on his feast day (17 July, the date when he was either murdered or buried at Winchcombe) were immensely popular. Chaucer even alludes to St. Kenelm in the Nun's Priest's Tale in his Canterbury Tales.

Charters witnessed by the historical Kenelm show that he was at least 25-years old in 811 CE, the probable year of his death, and there is no evidence indicating he was murdered in a plot involving his sister. Cwenthryth, it is known, entered the Abbey at Minster-in-Thanet after her father died and she came into possession of his lands. The altercation with Wulfred began shortly after her arrival there.

The people of the time, however, had no access to these records and were largely illiterate. They would have had accounts like The Story of St. Kenelm the Little King read to them and would have then repeated the story to others. In time, Cwenthryth became the evil sister who orchestrated the death of her innocent little brother; a reputation she has had ever since.

Cwenthryth in Vikings & Other Evil Queens

In the TV series Vikings, Kwenthryth is not evil so much as damaged by abuse at the hands of her uncle, brother, and other men of the Mercian court and is also depicted simply as a woman attempting to assert herself in a patriarchal role. Even so, her character is drawn from the legendary Cwenthryth as well as the two other queens mentioned above Cynethryth and Eadburh of Mercia.

Cynethryth's reputation has been tarnished just as badly as Cwenthryth's as later scribes characterized her as scheming, manipulative, and murderous. According to one tale, her daughter Alfrida fell in love with the handsome prince Ethelbert of East Anglia and asked her father to arrange a marriage. Offa did so but Cynethryth became jealous of her daughter's happiness and convinced Offa that Ethelbert was plotting against him. Offa invited Ethelbert to his palace and, on the night before the wedding, had him killed in the great hall.

When Offa's men tried to bury the body, however, angelic lights would appear to expose the crime and they had to try again to find a less conspicuous site for the burial. At last they managed to bury Ethelbert in Hereford where a wonderous spring then burst from the ground, very like in the Kenelm tale and many others. Cynethryth, after a life of deceit and murder, improbably retired to an abbey after the death of her husband in order to contemplate the divine.

Long before her retirement, however, Cynethryth taught her deviousness to her daughter Eadburh who was married to Beorhtric of Wessex (r. 786-802 CE). Eadburh is characterized by the scribe Asser (d. 909 CE) as a “tyrant” who would either convince her husband to have various people killed or did so herself by poisoning them. She is said to have poisoned her husband by accident in an attempt to kill one of his favorite court counselors and, afterwards, to have fled Wessex for the kingdom of the Franks.

Once there, in a famous – and almost certainly fictional - medieval moment, she was asked by Charlemagne which she would choose in marriage, himself or his son. When Eadburh chose the younger man, Charlemagne informed her that, had she chosen him, she would have had both of them but, since she chose his son, she would have neither. She was then expelled from his castle but made abbess of a convent. She is then said to have violated all the codes of sanctity through sexual relations with a man and was thrown out to spend the rest of her days begging in the streets.

Documents and letters of the time, however, suggest that these women were nothing like their depiction in the works of the later scribes who wove their legends. Cynethryth is praised by the famous scholar and cleric Alcuin (c. 735-804 CE) for her piety and attention to the church and there are no reliable accounts of her alleged murderous tendencies. There is evidence however that, like Cwenthryth, Cynethryth challenged the authority of the Archbishop of Canterbury over land rights and, as in the later event, the church won.

In the case of Eadburh, it is easy to understand where the resentment of the later scribes (like Asser) comes from: Eadburh was the means by which Mercia controlled Wessex. Asser complains, at one point, how “as soon as she had won the king's friendship, and power throughout almost the entire kingdom, she began to behave like a tyrant after the manner of her father” (Keynes & Lapidge, 71). Eadburh's marriage was arranged for the express purpose of Mercian control over the southern reaches. Beorhtric needed Mercian support to win the Wessex throne from his challenger (the future Egbert of Wessex, r. 802-839 CE). Offa gave him this support and, in exchange, Beorhtric married Eadburh who then helped shape Wessex's policy and decisions regarding Mercia. It is hardly surprising, then, that later scribes from Wessex should cast her in a negative light.

In Vikings, Kwenthryth is promised support by King Ecbert of Wessex who sends his son Aethelwulf and the Viking mercenaries under Ragnar Lothbrok to defeat Kwenthryth's uncle and brother and restore her to the Mercian throne. Once this is accomplished, Kwenthryth poisons her brother Burgred at a celebratory feast and assumes the throne of Mercia. Ecbert eventually betrays Kwenthryth and kills her with the help of his mistress (also his daughter-in-law) Judith. None of these events is historical but they do point to a historical truth.

In the TV show, Kwenthryth is depicted as a strong and determined, if damaged, woman fighting for the same recognition and rights given to men and, in the end, is betrayed; the same can be said for the historical figures who inspired the character. Cynethryth, Eadburh, and Cwenthryth were all women who challenged the patriarchal authority of the church or crown and would be betrayed by the scribes who later wrote the tales about them which came to be regarded as history.