Although women in the Viking Age (c. 790-1100 CE) lived in a male-dominated society, far from being powerless, they ran farms and households, were responsible for textile production, moved away from Scandinavia to help settle Viking territories abroad stretching from Greenland, Iceland, and the British Isles to Russia, and were perhaps even involved in trade in the sparse urban centres. Some were part of a rich upper class, such as the lady – perhaps a queen – who was buried in the ostentatious Oseberg ship burial in 834 CE, while on the other end of the spectrum, slaves, among them many women, were taken from conquered territories during the Viking expansion and integrated into Viking Age society.

As we are largely dependent on piecing together their lives mostly through burials, the accompanying grave goods, and the occasional runestone that mentions women (or was commissioned by one), we know a fair amount about Viking Age women's clothing, jewellery, and personal items but much less about their effective 'power' or the status they held. In a landscape where small rural communities or even remote self-sustaining farmsteads were the norm, however, the domestic tasks that were mainly the domain of women were clearly far from unimportant. In some cases, while their men were away trading, or pillaging monasteries and scaring monks around the Northern European coasts, the wives who stayed behind likely took over control of the farm for a while. Moreover, over the past few years, the possible existence of female Viking warriors has been discussed a lot – adding high-pitched battle-screams to an otherwise very bearded scene – but the evidence is quite controversial and inconclusive.

Clothing & Jewellery

One of the less cloudy areas when it comes to the lives of women in the Viking Age is their clothing and jewellery. Courtesy of burials and their accompanying grave goods, we know that most women seem to have worn outfits comprised of two or three layers, the first of which being a linen or woollen sleeved shift or underdress fastened at the neck with a small disc brooch and sometimes pleated there, too. On top of this, a strapped gown or overdress was worn, made of a rectangular piece of usually wool which was wrapped around the body and held up by shoulder straps which at the front of the dress were pinned down by two oval brooches.

These oval brooches, also known as tortoise brooches, are typical for Viking Age material culture, and when one finds such brooches in graves, a Scandinavian link is usually present. They varied hugely in style; more than 50 styles have been identified, and, as Neil Price explains, "the differences may reflect changes in fashion, but it is more likely this enormous diversity shows an arcane language of class and regional affiliation we can no longer understand." (Fitzhugh & Ward, 36). Alternatively, box brooches could also be used to fasten shawls and the likes. Both types of brooches were usually made of bronze and adorned with knotted patterns. The types of textiles held in place by them could vary greatly too, from simple domestic wool to fine oriental silk in trading hubs such as Birka in Sweden, where, interestingly, the varying qualities of cloth were often present in one and the same (rich) grave.

Besides these practical items, women in the Viking Age also wore necklaces, arm rings, and trefoil buckles (and trefoil brooches, made up of three 'arms' poking out, embellished with knotwork and/or filigree). Beads are also commonly found in their graves.

Running the Household

Although a few trade centres did exist, Viking Age homes were mostly located in smaller rural hubs and at isolated farms where a large degree of self-sufficiency would have been needed to survive. A typical Viking Age house was made up of one long room with a central hearth and could be accompanied by a dairy, sheds, barns, and other outbuildings.

Mostly resigned to this domestic sphere, Judith Jesch remarks that "women living in rural areas in the Viking Age spent most of their time in the triangle of byre [cowshed], dairy and living quarters, providing their families with food and clothing" (41). Just as food had to be prepared from whatever raw state it came in – quite unlike running to the supermarket – textile production and the subsequent making of clothes were elaborate processes that almost all Viking Age women were involved in one way or another. In fact, the most common grave goods found in female graves from this period are spindle whorls, wool combs, and weaving battens, especially in the countryside. Other tasks that do not show up in the archaeological record in such a direct way but are traditionally associated with women are child-rearing and caring for the sick or the elderly, and we might also imagine women doing odd jobs around the farm or even some carpentry or leatherworking. How exactly children were brought up and whether girls were treated any differently from boys is unclear, although daughters could perhaps be given in marriage at an appropriate age.

Although subordinate to their husbands, like their contemporaries, women arguably had a good degree of responsibility and perhaps even control over the running of the household, as symbolised by the fact they were often buried with keys, and they were likely on occasion left in charge of matters while their husbands were away (or dead). Anne-Sophie Gräslund has even suggested farms were like firms, "run by husband and wife together, in which the work of both partners was of equal importance although different and complementary" (Sørensen, 260). It must be noted, though, that the people who owned such (larger) farms and their adjoining lands would have had considerable means and would likely have belonged to the upper classes within society; they are not automatically reflective of all of Viking Age society. Throughout Viking Age society, though, marriage was a pivotal institution used to create new ties of kinship, also among Scandinavians and locals in conquered or settled areas, and, in line with the influence women could wield through their husbands, it seems unmarried women had very limited prospects. Before the advent of Christianity throughout Scandinavia and Viking territories around 1000 CE, concubinage (often connected to slavery), and plural marriages occurred at least among the royals.

In general, although it is hard to comment on the exact status of Viking Age housewives, we must remember their domestic role was a very central one and would not generally have gone unappreciated. The inscription found on a stone as Hassmyra (Vs 24) – the only verse found on a Swedish inscribed stone that commemorates a woman – certainly seems to confirm this:

The good farmer Holmgaut had this raised in memory of his wife Odindis.

A better housewife

will never come

to Hassmyra

to run the farm.

Red Balli carved

these runes.

She was a good sister

to Sigmund.(Jesch, 65)

Possible tradeswomen

There were a few trading centres in Viking Age Scandinavia where a lot more hustle and bustle must have gone on and where families would have lived slightly different lives than their more isolated and rural counterparts. The largest of these centres were Birka in Sweden, Ribe in Denmark, Kaupang in Norway, and Hedeby in present-day northern Germany (on the southern edge of Viking Age Denmark). Whereas in the countryside women were often buried with spindle whorls, female graves unearthed at Birka, for instance, hold needles, scissors, and tweezers, hinting at fine sewing, and even merchants' weights, scales, and coins.

These latter have been found not just around other urban centres in Scandinavia but also in Viking territories across what is now Russia, and have been taken to indicate that these women had been traders. Directly linking grave goods to actual activities in life is always a bit risky, though, as we do not know the intentions with which they were buried. Judith Jesch sensibly cautions that,

…we need to consider whether grave goods really represent the former lives of the dead, or whether some of them could not in fact have more of a symbolic function. The presence of weights in children's graves does not necessarily mean that they engaged in trading activities too. (Jesch, 21)

Instead, as has indeed been proposed by others, a woman buried with weights and scales may simply have belonged to a family of merchants rather than she herself having been an active merchant. As with many things regarding women in the Viking Age, we just do not have enough information to fill in such blanks or to paint a detailed picture of what exactly an urban Viking Age woman's life would have looked like. However, women in trade centres would certainly have been more directly connected with the wider world, not just through 'exotic' goods coming in but also through visitors. An account that relays how in the 9th century CE a Christian mission was sent to Birka and successfully converted the rich widow Frideburg and her daughter Catla, who then decided to travel to the Frisian market town of Dorestad, illustrates this.

The Elite

If some women were indeed involved in trade, this might conceivably have placed them in the upper rungs of society or least given them means and status. The Viking Age's rich and powerful – a group which obviously was not exclusively male – peep through the gap of time and reach the modern world in a number of ways, such as the large runestones that were erected across Scandinavia, and burials ranging from just 'rich' to ones so over the top it leaves us no doubt as to the buried person's importance.

Runestones – unsurprisingly, big stones covered in runes and ornamentation usually erected to commemorate the dead – were normally commissioned by wealthy families, the runes speaking of their endeavours in life. Not only can one imagine women being important within these families, some stones were actually commissioned by women themselves (either jointly or alone), leaving an "impression of high social standing of a very few women" (Jesch, 49-50). Runestones also illustrate how important the inheritance of a woman was to facilitate the transfer of wealth from one family to another. Furthermore, some richly furnished female graves (and even boat graves) found in rural settings hint at women possibly climbing to high social positions there. In this same setting, we have already seen that women might have ended up running the farm in their husbands' absence.

Some 40 graves from Scandinavia and beyond have lent some credence to the idea, stemming from the texts and sagas related to the Viking Age, of the existence of female 'sorceresses'. Seiðr is a type of shamanistic magic mainly connected to women in the sources, who could be völur (singular: völva): powerful sorceresses with the power to see into the future and mainly associated with a staff of sorcery. Similar objects have been discovered in Viking Age burials and have clear symbolic overtones, perhaps even - according to one interpretation - functioning as metaphorical staffs used to 'spin out' the user's soul. These graves are often rich in terms of clothes and grave goods and include such things as amulets and charms, exotic jewellery, facial piercings, toe rings, and, in a handful of graves, even psychoactive drugs such as cannabis and henbane. How we might imagine these women's roles in society remains mysterious.

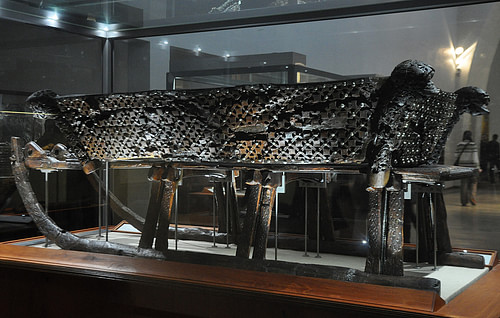

We also know of some royal female burials. Judith Jesch, mentioning the Oseberg boat burial (c. 834 CE) in which two women were buried in a lavishly decorated and furnished ship accompanied by lots of high-quality grave goods, explains how,

A few obviously royal burials that we have, such as Oseberg, cannot be mistaken for anything other than the monuments of persons with enormous status, wealth and power. Although they share characteristics with other Viking Age burials, they are really in a class of their own. (27)

Who exactly these women had been in life – queen and handmaiden, two aristocratic women related to each other, or otherwise – remains a puzzle but that at least one of them was of high status is beyond doubt.

Another woman of plentiful means was the late-9th-century CE Aud the 'deep-minded'. She is said to have been born to a Norwegian chieftain residing in the Hebrides and married a Viking who lived in Dublin. After the death of both her husband and son, she took over control of the family fortunes and arranged for a ship to take her and her granddaughters first to Orkney and the Faroes, to finally settle in Iceland. Here, she distributed land among her retinue, became an early Christian, as well as being remembered as one of Iceland's four most important settlers.

To top off the elite category, Viking Age queens existed, some on a smaller local scale (the big unified Scandinavian kingdoms did not fully crystallise until the end of the Viking Age), and some of them may have been very well-connected. All Viking Age women may, of course, have exercised influence through their husbands or sons – the more important they were, the more opportunities this might have entailed for the women at their sides.

Women As Settlers

In the wake of the Viking raids spilling across northern Europe and beyond, Viking territories sprung up as far apart as Greenland (and even Newfoundland in North America) and Russia. It is obvious that proper settlement is a hard thing to achieve without women, and female Viking Age burials – with their famous oval brooches – across these areas confirm their presence.

On the one hand, in the Vikings' initial raiding waves and military expeditions, it is both hard to picture women taking an active part and hard to find any evidence of this, although late-9th-century CE Anglo-Saxon and Frankish sources relate how Viking forces travelled together with their women and children, and archaeological finds at winter camps such as that at Torksey (England) reveal evidence of textile manufacture. Such families or camp-followers need not have been Scandinavian women, though; the Viking armies raided both the continent and the British Isles and would likely have picked up at least some of the women from here. How common this scenario was is unclear, too.

On the other hand, more clarity arrives with the first proper settlement waves (times varied per Viking territory): Scandinavian immigrant families arrived in the British Isles in phases during the 9th and 10th centuries CE, while towards the end of the 9th century CE Iceland (and later, Greenland and beyond) were settled. These latter areas were fully Scandinavian (bar some influx of often female slaves, for example, taken from Ireland), while in the British Isles as well as through Russia there was more room for mixing with already-present people. On Orkney, for instance, the 9th- or early 10th-century CE burial of the so-called Westness Woman shows a Norse woman in her twenties along with her newborn child, buried with grave goods of a pair of bronze oval brooches as well as a Celtic pin among others. A rich Scandinavian female grave on the Isle of Man (the 'Pagan Lady of Peel') coupled with the c. 30 Christian runic monuments that are basically Celtic crosses with runic inscriptions (including both Norse and Celtic personal names) with Scandinavian-style ornamentation shows an even stronger image of a mixed community.

Warrior Women?

The famous Icelandic sagas of the 13th century CE, relaying stories set in the earlier Viking Age, add another possible layer of depth to the role of women; they are shown as strong women taking action, stoking up revenge, standing up to their husbands or even engaging in fights. However, these sagas were composed way after the time they wrote about, from a different context, and it is too much of a stretch to directly extrapolate this image of women to the actual Viking Age.

Nevertheless, the 'strong Viking woman' runs wild in popular imagination. When Charlotte Hedenstierna‐Jonson published an article titled 'A female Viking warrior confirmed by genomics' (2017), for instance, excitement seemed to overtake caution. The study discusses a Viking Age grave (Bj 581) found in Birka, Sweden in the 1800s CE, containing a skeleton alongside various weapons, horses and even a stallion; seemingly the attributes of a warrior. The tested bones belonged to a woman, who was subsequently dubbed "the first confirmed female high‐ranking Viking warrior" (857) on the basis of there also being a set of gaming pieces present (which the authors equate to tactical and strategical knowledge).

Critics have noted that this assumption belongs more in the realm of speculation rather than actual fact. The skeleton had no traumatic injuries – not something one would expect from an active warrior – and showed no sign of strenuous physical activity. We must remind ourselves how difficult it is to link grave goods to a person's actual life – could this woman have been buried with this warrior's gear for another reason (perhaps symbolic)?

If more evidence along those lines comes to the fore regarding women, the story changes, but as of yet, it would appear the archaeological and historical evidence is not sufficient to confirm this Birka woman having been an active warrior. Here, too, the lives of women in the Viking Age remain more shrouded in mystery than that of their male counterparts.