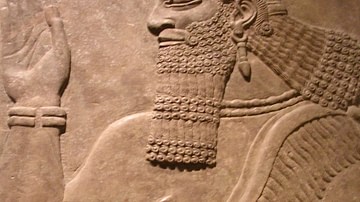

Zakutu (l. c. 728 - c. 668 BCE) was the Akkadian name of Naqi’a, a secondary wife of Sennacherib of Assyria (r. 705-681 BCE). Though she was not Sennacherib's queen, she bore him a son, Esarhaddon, who would succeed him. She may have ruled briefly as queen after Esarhaddon’s death and was grandmother to his successor, Ashurbanipal.

She is best known for the Zakutu Treaty which ensured a smooth transition of power after Esarhaddon (r. 681-669 BCE) died unexpectedly on campaign in Egypt. Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE) was able to assume the throne without challenge due primarily to his father’s careful planning and the claim that Zakutu was responsible for Ashurbanipal’s rise to power has been discredited. Her treaty only ensured that Esarhaddon’s wishes were honored by the court and nobility.

She is the only Assyrian queen (except, possibly, for Sammu-Ramat, r. 811-806 BCE), to issue a royal document under her own name and to have commissioned any building projects. Writings about Zakutu come mainly from the reign of Esarhaddon and give evidence of a strong and clever woman who rose from obscurity to greatness. Almost nothing is known of her youth or life prior to her association with Sennacherib and, after Ashurbanipal became king, she retired from public life (or soon died) and vanishes from the historical record.

Wife of Sennacherib

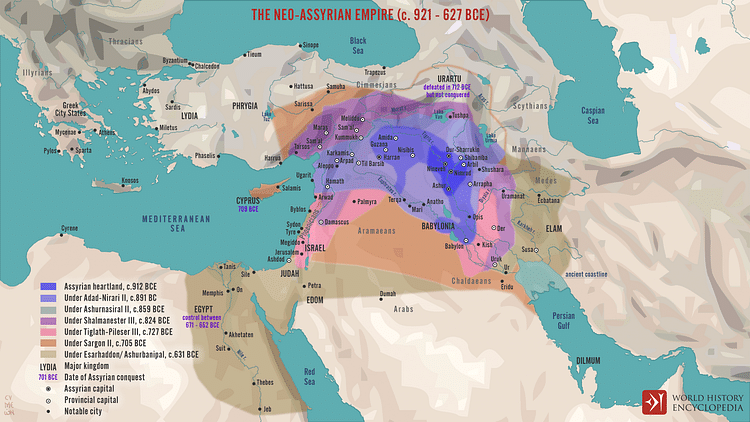

Sennacherib was the son and successor of Sargon II (r. 722-705 BCE) whose military campaigns, cultural incentives, and building projects elevated the Neo-Assyrian Empire to its greatest height. While Sargon II was away on campaigns, Sennacherib was entrusted with governing the empire and was essentially king in everything but name. He took a wife, Tashmetu-sharrat (d.c. 684/681 BCE) at some point who became his primary consort and was known as his queen. An inscription dated to c. 696-693 BCE by Sennacherib, dedicated to Tashmetu-sharrat, expresses his devotion to her and his hopes that they might live together forever. In keeping with tradition, however, Sennacherib had a number of secondary wives and, among them, was Zakutu.

It is unclear when he married Tashmetu-sharrat, who would bear him several children, but he was intimately associated with Zakutu prior to 713 BCE when she gave birth to his son Esarhaddon. Sennacherib had other wives besides Tashmetu-sharrat and Zakutu and so it is unclear who was the mother of which of his eleven sons (possibly more) and an unrecorded number of daughters but, of the boys, Esarhaddon is recorded as the son of Zakutu. It is also understood that he was the youngest and so stood the least chance of being named his father’s successor. As Zakutu was considered merely a 'palace woman', not a noble, the elder brothers seem to have taken little notice of her or her son.

Sennacherib's favorite son and chosen heir, Ashur-nadin-shumi, was appointed ruler of Babylon from which he was kidnapped by the Elamites sometime around 695 BCE. He was most likely killed by his captors c. 694 BCE (his fate is unknown) and Sennacherib needed to choose one of his brothers to replace him as heir. During this period, the king was busy with military campaigns and then building projects in and around Nineveh and seems to have taken his time making his decision regarding a successor. It is possible that he was evaluating his sons to see who was most fit to rule after him.

It would no doubt have come as an unpleasant surprise to Esarhaddon's older brothers when, in 683 BCE, Sennacherib chose his youngest son to succeed him. Some scholars maintain that Zakutu's maneuvering was behind the decision, but this claim has been challenged. The death date of Tashmetu-sharrat is unknown (c. 684/681 BCE is a best guess) but it seems likely she had passed prior to 683 BCE as Sennacherib was clearly devoted to her and so might have chosen one of her sons as his successor were she still alive. This claim is speculative, however, as is any assertion that Zakutu took the place of Tashmetu-sharrat as primary consort.

Esarhaddon’s brothers took great exception to their father’s choice and, in fear for his life, Zakutu sent him into hiding somewhere in the region formerly known as Mitanni. Two of Sennacherib's sons assassinated the king in 681 BCE and the murder is regularly attributed to his sacrilege in destroying the city of Babylon and carrying off the statue of the great god Marduk, but it is equally probable they killed him simply to gain the throne and disenfranchise their younger brother. Esarhaddon was then recalled from exile, probably by Zakutu, defeated his brothers in a six-week civil war, and took the throne; afterwards, he had his brothers’ families and associates executed.

Mother of the King

Although little is known of Zakutu’s youth or origin, her name Naqi’a is Aramaic/Semitic and Zakutu is Akkadian, suggesting (as scholar Wolfram von Soden maintains) she came from the region of modern-day Syria. From a land purchase contract, it is known that she had a sister, Abirami, but no other personal details of Zakutu's life have come to light. Her name – Naqi’a-Zakutu – means “pure one” in their respective languages. She seems to have become best-known as Zakutu in the modern age owing to the opening line of her famous treaty where she uses that name.

Zakutu held an impressive place at court during the reign of Esarhaddon and seems to have been known as Queen and Queen-Mother. She drafted letters and received foreign dignitaries as a monarch even though she was not Assyrian and had never been primary consort or queen to Sennacherib. Letters on important matters were addressed to her and, in keeping with royal protocol, were addressed to the “mother of the king” and included traditional salutations used in speaking or writing to a monarch.

Zakutu’s wealth, power, and prestige is evident in her grand building project of a palace at Nineveh for her son between c. 677-673 BCE. She not only commissioned the work, but did so under her own name which, as scholar Sarah C. Melville notes, was unheard of in Assyrian tradition:

In the ancient Near East, monumental building projects were an important indicator of royal competence and the fiscal health of the state. One of the king’s chief duties was to sponsor construction of palaces, temples, aqueducts, quays, and military installations as proof of his power and ability to provide for his people. Public works projects were implemented throughout the empire at sites chosen both for their propaganda value and in response to need. For anyone other than the king – especially a woman – to build on the king’s behalf was unprecedented in Assyria and might easily have been misconstrued as a sign of royal weakness. What kind of king would let his mother/a woman build a palace for him? Could he not build one for himself? However, the fact that Esarhaddon undertook numerous building projects at Nineveh, elsewhere in Assyria, and in other parts of the empire, undoubtedly mitigated any negative impact his mother’s project might have had. On the contrary, Esarhaddon most likely endorsed [his mother’s] involvement in a large-scale building project in order to proclaim publicly that she was an important figure at court. (Chavalas, 229-230)

There is no evidence that anyone thought less of Esarhaddon for his mother’s work nor that her efforts undermined her son’s authority. This suggests that Zakutu was already well-known and respected for her own accomplishments and contributions to social well-being although the details of what she may have done are unknown.

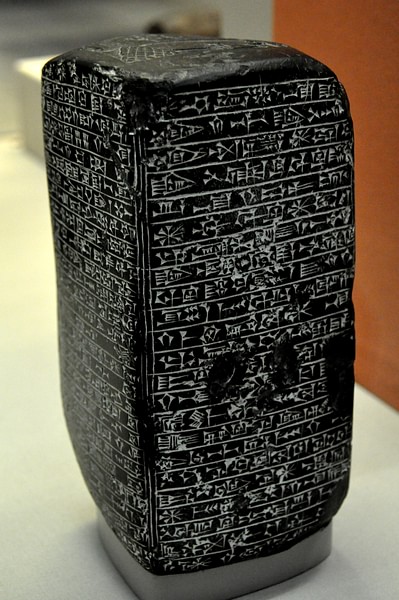

The Palace Inscription

It is clear, however, that she commissioned her son’s palace at Nineveh and made that known through the inscription she had placed in its foundation. Melville elaborates:

Normally, the Assyrians celebrated public building projects with commemorative inscriptions, which could be buried in foundation deposits so that later kings (and the gods) would know who had undertaken construction, or displayed on walls, floors, or stelae in order to reach a wider audience…Naqi’a’s building inscription follows this same basic formula with modifications that reveal the scribe’s careful attention to the protocols and etiquette of rank. That is, Naqi’a’s inscription is intentionally shorter and more modest than the typical royal type; she does not overstep her position. (Chavalas, 230)

Zakutu is careful to limit herself to inviting the gods of the city to the grand opening of the palace, not all the gods of Assyria, as would be in keeping with royal inscriptions of a king. She later (as seen below) invokes a wider array of gods in gratitude for her son’s victories, not for her own accomplishments. She also makes sure to clearly state that it was Esarhaddon, not she, who furnished the necessary materials and labor so that the king would ultimately receive credit for the project. Her inscription reads, in part:

Naqi’a-Zakutu, consort of Sennacherib, King of the world, King of Assyria, daughter-in-law of Sargon, King of the world, King of Assyria, Mother of Esarhaddon, King of the world, King of Assyria. The gods Ashur, Sin, Samas, Nabu, Marduk, Ishtar of Nineveh and Ishtar of Arbela were pleased, and they gladly put Esarhaddon, my offspring, on the throne of his father. From the top of the upper sea to the lower sea they constantly patrolled…They destroyed his [Esarhaddon’s] enemies and they put the nose rope on the kings of the four quarters. People of all the lands, enemy captives that were his part of the plunder, he gave as my lordly portion, and I had them carry the hoe and the dirt basket and they made bricks. A piece of undeveloped land in the midst of Nineveh behind the Sin and Samas temple [I chose] for a royal residence of Esarhaddon, my beloved son… (Chavalas, 230)

Zakutu may have been able to so easily commission her son’s palace, and announce her part in it, because the people are thought to have associated her with the divine force of Ishtar. Esarhaddon was often ill during his reign, and it may have been thought that his mother’s devotion to the goddess of war, love, and sexual energies, gave him the strength and vitality to not only rule but campaign and build successfully.

Treaty of Zakutu

Esarhaddon wanted to spare his sons the difficulty he had experienced when he came to the throne and so, after his eldest son and heir, Sin-iddina-apla, died in 672 BCE, he had his vassal states swear their allegiance to his second son Ashurbanipal. He left to campaign in Egypt after instructing that his youngest son, Shamash-shun-ukin, be proclaimed king of Babylon.

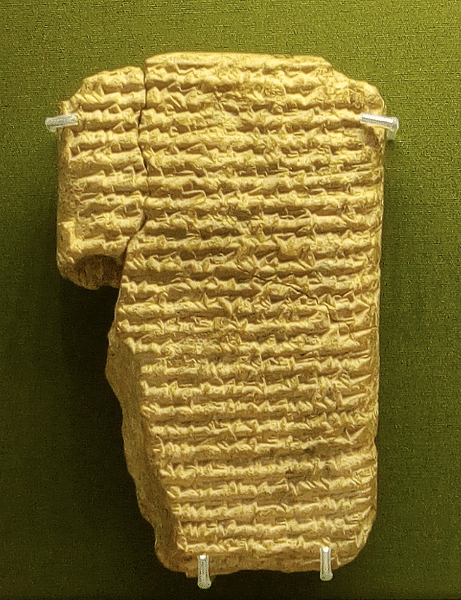

He died on the Egyptian campaign and, either just before or right after his death in 669 BCE, Zakutu issued her loyalty oath (in either 670 or 668 BCE) known as the Loyalty Treaty of Naqi’a-Zakutu or the Treaty of Zakutu to ensure that the court and vassal states recognize her grandson Ashurbanipal as their king in accordance with his father’s wishes. In the following passage, the word grandmother is given in brackets as it is suggested but not wholly present in the text. This same holds for other words or parts of sentences in brackets. The treaty reads, in part:

Treaty of Zakutu, consort of Sennacherib, King of Assyria, mother of Esarhaddon, King of Assyria, [grandmother of Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria]…Anyone who concludes this treaty which Zakutu, the queen dowager, has imposed on all the people of Assyria on behalf of Ashurbanipal, her favorite grandson, anyone who should…lie and carry out a deceitful or evil plan or revolt against Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord; in your hearts plot evil intrigue or speak slander against Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord; in your hearts contrive or plan an evil mission or wicked proposal for rebellion and uprising against Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord…or conspire with another for the murder of Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord…from this day on, [should you] hear an evil plan of conspiracy and rebellion against Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord, you shall come and report to Zakutu, [his grandmother] and Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord; and if you hear of a plot to kill or destroy Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord, you shall come and report to Zakutu, his [grandmother] and Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord; and if you hear of evil intrigue being contrived against Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord, you shall speak of it in the presence of Zakutu, his [grandmother] and Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord; and if you hear and know that there are men who agitate or conspire among you – whether bearded men or eunuchs, whether his brothers or royal relatives or your brothers or your friends or anyone in the whole country – should you hear or know, you shall seize and kill them and bring them to Zakutu, his [grandmother] and Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria, your lord. (Chavalas, 231-232)

The treaty clearly identifies Zakutu as queen dowager at this time and the fact that she could issue such a decree indicates she enjoyed sufficient power and support to be able to ensure the succession of her grandson as king. As noted, the treaty was once understood as a power play on Zakutu’s part to advance the fortunes of her favorite grandson, but modern scholarship has dismissed this claim as it is clear that Esarhaddon had already made provision for his successor and Zakutu was only making sure that his wishes were honored.

Conclusion

Once Ashurbanipal was installed as king, he made provision to honor his younger brother by decreeing a coronation festival for him as King of Babylon. He continued his father’s policies of restoring Babylon to its former glory (prior to the sack of Sennacherib) and secured the southern territories before embarking on campaign to Egypt. Zakutu still held a prominent place at court during this time and, presumably, continued to correspond with and receive emissaries of foreign dignitaries. Von Soden describes Zakutu's continued importance at court:

The Syrian-born wife of Sennacherib, Naqi’a-Zakutu, still possessed considerable influence during the first years of the reign of her grandson, Ashurbanipal, and was feared by the royal officials. (67)

Her death date is usually given as c. 668 BCE, but she clearly lived at least a few years into Ashurbanipal’s reign before retiring from public life or dying. Precisely how she was able to ascend to her position of power at Sennacherib’s court is unknown – though the answer may be waiting in future archaeological excavations in the region – but it is clear she played a pivotal role in the rise of two of the most important kings of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. She is best remembered, however, for the impressive accomplishment of elevating herself from the nearly invisible position of a `palace woman’ to one of the most prominent figures of the royal Assyrian court.