Marduk was the patron god of Babylon who presided over justice, compassion, healing, regeneration, magic, and fairness, although he is also sometimes referenced as a storm god and agricultural deity. His temple, the famous ziggurat described by Herodotus, is considered the model for the biblical Tower of Babel.

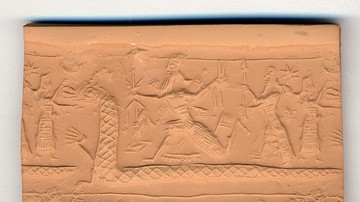

The Greeks associated him with Zeus and the Romans with Jupiter as he was known as the Babylonian King of the Gods. He is depicted as a human in royal robes, carrying a snake-dragon and a spade. Marduk seems to have originated from a local deity known as Asarluhi, a farmer's god symbolized by the spade, known as a marru, which continued as part of his iconography. Marduk's name, however, though linked to the marru, translates as 'bull-calf,' although he was commonly referred to simply as Bel (Lord). Far from the local deity he sprang from, Marduk would become one of the most prestigious gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon.

He was the son of the god of wisdom Enki (also known as Ea, considered a creator god in some myths) who was also associated with fresh, life-giving water. Marduk's association with Enki is no doubt linked to the earlier regional deity Asarluhi who had the same relationship and shared many of Marduk's characteristics. Marduk's wife was the fertility goddess Sarpanitu (though in some myths his wife is Nanaya), and their son was Nabu, the patron god of scribes, literacy, and wisdom.

From a regional agricultural deity, Marduk took on increasing significance for the city of Babylon (and later the Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian Empire) becoming finally the most important and powerful god of the Babylonian and wider Mesopotamian pantheon and attaining a level of worship bordering on monotheism. He was regarded as the creator of the heavens and earth, co-creator with Enki of human beings, and originator of divine order following his victory over the forces of chaos led by the goddess Tiamat, as told in the Enuma Elish. Once he legitimized his rule, he conferred upon the other gods their various duties and responsibilities and organized both the world and the netherworld.

Marduk in the Enuma Elish

The Babylonian creation myth, Enuma Elish, tells the story of Marduk's rise to power. In the beginning of time, the universe was undifferentiated swirling chaos which separated into sweet fresh water, known as Apsu (the male principle) and salty bitter water known as Tiamat (the female principle). These two deities then gave birth to the other gods.

Tiamat loved her children, but Apsu complained because they were too noisy and kept him up at night while distracting him from his work during the day. Eventually, he decided to kill them and Tiamat, horrified, told her eldest son Enki about the plan. Enki then considered the best possible course of action, put his father into a deep sleep, and killed him.

From Apsu's remains he created his home, the earth, in the marshy region of Eridu. Tiamat never expected her son to kill his father and so declared war on her children, raising up an army of chaos to assist her. At the head of her forces she placed the god Quingu, her new consort, who is victorious over the younger gods in every battle.

Enki and his siblings begin to despair when the young god Marduk steps forward and says he will lead them to victory if they will first proclaim him their king. Once this is accomplished, Marduk defeats Quingu in single combat and then kills Tiamat by shooting her with an arrow which splits her in two; from her eyes flow the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and, from her corpse, Marduk forms the heavens and completes the creation begun by Enki of the earth (in some myths Enki is not mentioned and Marduk is the sole creator of the world). In consultation with Enki, Marduk then created human beings from the remains of the defeated gods who had encouraged Tiamat to wage war on her children. The defeated Quingu is executed, and his remains used to create the first man, Lullu.

Marduk then regulates the workings of the world which includes humanity as co-workers with the gods against the forces of chaos. Henceforth, Marduk decrees, humans will do the work which the gods have no time for, freeing the divine to concentrate on higher purposes and care for human needs. As the gods will care for humans and supply all their needs, humans will respect and heed the will of the gods, and Marduk will reign over all in benevolence.

Marduk's Reign in Babylon

This reign was centered, not in the heavens, but in the temple - the Esagila - in Babylon. Deities in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and elsewhere were thought to literally reside in the temple built for them, and this was as true for Marduk as any other deity. Marduk came to prominence in Babylon during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE). Prior to the elevation of Marduk, Inanna - goddess of sexuality and warfare - was the principal deity worshiped in Babylon and elsewhere throughout Mesopotamia; afterwards, although Inanna continued to be widely venerated, Marduk was the supreme deity of the city and his worship spread as Babylon conquered other regions. Scholar Jeremy Black writes:

The rise of the cult of Marduk is closely connected with the political rise of Babylon from city-state to the capital of an empire. From the Kassite Period, Marduk became more and more important until it was possible for the author of the Babylonian Epic of Creation to maintain that not only was Marduk king of all the gods but that many of the latter were no more than aspects of his persona. (128)

The golden statue of Marduk, housed in the inner sanctum of his temple, was considered a vital aspect of the coronation of kings. A new king needed to 'take the hands of Marduk' to legitimize his rule, a practice which seems to have been initiated during the Kassite Period (1595-1155 BCE) when the Kassites made Babylon their capital after driving out the Hittites.

Some scholars maintain that the new king had to literally take the hands of the statue - and this seems to be corroborated by ancient texts on the subject - while others claim 'taking the hands of Marduk' was a symbolic statement referring to submitting to the guidance of the god. It seems likely, however, based on the ancient written evidence, that the statue needed to be present at the succession of a new ruler and that the king needed to actually touch the statue's hands.

Marduk Prophecy

The importance of the statue is attested by the ancient work known as The Akitu Chronicle which relates a time of civil war in which the Akitu Festival (New Year's celebration) could not be observed because the statue of Marduk had left the city. On New Year's day, it was customary for the people to carry the statue of Marduk through the city and out to a little house beyond the walls where he could relax and enjoy some different scenery.

During those times when the statue was carried off by hostile nations, the Akitu festival could not be observed because the patron god of the city was not present. Further, disaster was thought imminent when the god was not in the city as there was no one to stand between the people and the forces of chaos. This situation is depicted clearly in the document known as The Marduk Prophecy (c. 713-612 BCE, though the story is probably older) which relates Marduk's 'travels' when his statue is stolen from the city during various eras. Scholar Marc van de Mieroop comments:

The absence of the patron deity from his or her city caused great disruption in the cult [of that deity and city in general]. The absence of the divinity was not always metaphorical but often the result of the theft of the cult statue by raiding enemies. Divine statues were commonly carried off in wars by the victors in order to weaken the power of the defeated cities. The consequences were so dire that the loss of the statue merited recording in the historiographic texts. When Marduk's statue was not present in Babylon, the New Year's festival, crucial to the entire cultic year, could not be celebrated. (48)

The Marduk Prophecy relates how the Hittites, Assyrians, and Elamites all captured Marduk's statue at one time or another and how it was finally returned to the city when King Nebuchadnezzar I (r. 1121-1100 BCE) defeated the Elamites. The document is written as though Marduk himself chose to visit those foreign lands - except for Elam - and how it was prophesied that a great Babylonian king would rise and bring the god back from the Elamites.

The Marduk Prophecy was most likely written as a propaganda piece during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I, although the only extant copy is a much later Assyrian copy. This work, as well as the Akitu Chronicle and others, make clear how vital Marduk's presence in the city was to the people. Without their divine protector the people felt helpless, knowing that they and their city were left vulnerable to widespread and also personal attacks.

Marduk the Protector

Although Marduk is referenced in a number of works throughout Mesopotamian literature, two of them make especially clear how dangerous life was for a person or city once one's god was absent. The Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi (c. 1700 BCE) and The Wrath of Erra (c. 800 BCE) treat of the individual's problem and a city's suffering respectively, both making clear the necessity of a protector deity.

The Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi is a treatise on suffering, on why a good person should seemingly be punished for no reason, framed as a long complaint by Tabu-utu-bel, an official of the city of Nippur, another city in which Marduk was worshiped. The speaker relates how he has called out for help from his goddess but has not heard back from her. Marduk, from afar, tries to send him help but nothing can alleviate the suffering.

The speaker lists all of the good gifts Marduk tries to help him with, but none of them do any good and, possibly this is because Marduk is not close at hand. The Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi has often been compared to the biblical Book of Job in examining the problem of suffering and the seeming absence of one's god. The work never explicitly claims that Marduk has left the person but certainly implies that Marduk is 'far off' and can only send what meager help is available.

The Wrath of Erra is a very different work in which the war god Erra (also known as Irra or Nergal) becomes bored and falls into a lethargy which he feels can only be cured by attacking Babylon. He is urged to abandon his plan by other gods but ignores them. He travels to Babylon where he distracts Marduk by telling him that his clothes have become shabby and he should really attend to his wardrobe.

Marduk protests that he is too busy, but Erra assures him that all will be well and he, Erra, will watch over the city. Once Marduk leaves to have a new suit of clothes made, Erra destroys the city, killing the people indiscriminately until he is stopped by the other gods and called to account (in some versions he is stopped by Marduk's return). The piece ends with praise for Erra, god of war, who decided to spare a remnant of the city so it could be repopulated.

Marduk the protector was so important to Babylon's sense of security and personal identity that when the city revolted against Persian rule c. 485 BCE, the Persian king Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) had the statue destroyed when he sacked the city. After Alexander the Great defeated the Persians of the Achaemenid Empire in 330 BCE, he made Babylon his capital and initiated efforts to restore the city to its former glory but died before this could be accomplished. Worship of Marduk declined as the city steadily lost prestige and power. By the time the Parthians ruled the region in 141 BCE, Babylon was a deserted ruin and Marduk had been forgotten.