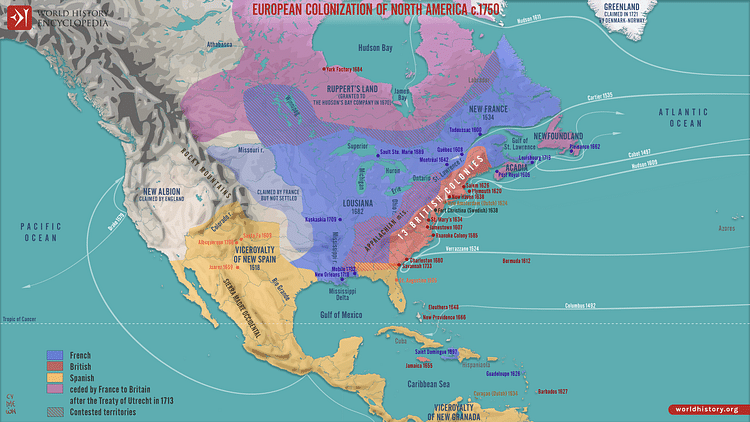

The European Colonization of the Americas was the process by which European settlers populated the regions of North, Central, South America, and the islands of the Caribbean. It is also recognized as the direct cause for the cultures of the various indigenous people of those regions being replaced and often eradicated.

The process of colonization developed fairly quickly between 1492-1620, with others arriving in larger numbers between c. 1620 - c. 1720, and still others afterwards up through the early 20th century. As more Europeans arrived, more land was required by them, steadily forcing Native Americans onto reservations as the immigrants enlarged their settlements.

The first European community in North America was established c. 980 - c. 1030 by the Norse Viking Leif Erikson (b. c. 970 - c. 980) in Newfoundland at the site known today as L'Anse aux Meadows. This settlement was temporary, however, and the Norse left to return to Greenland after a little over a year, inspiring no further expeditions to the site. Although Norse artifacts have been found along the east coast of North America – suggesting further explorations – this has not been established as evidence of a widespread Norse presence in the Americas.

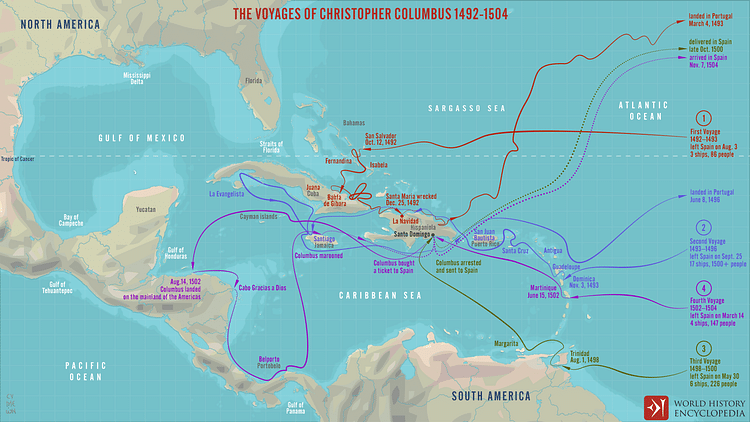

European colonization of the region is therefore cited as beginning with Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506) whose voyages to the West Indies, Central and South America, and other islands of the Caribbean between 1492-1504 introduced the so-called New World to European interests. Columbus was not attempting to discover the Americas but was seeking a new maritime route to Asia after the closure of the overland trade routes (known as the Silk Road) by the Ottoman Empire in 1453; an event which launched the so-called Age of Discovery. Columbus, sailing for Spain, opened the way for Spanish colonists to settle in the region he had explored, which would later lead to the Spanish Conquest of Central and South America throughout the 16th century.

The region of modern-day Brazil was claimed for Portugal in 1500 by the Portuguese aristocrat and mariner Pedro Álvares Cabral (l. c. 1468 - c. 1520) while parts of modern-day Canada were claimed for France after its exploration by the Florentine seaman and explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano (l. 1485-1528, who mapped the entire eastern seaboard of North America) in 1524, leading to the establishment of the colony of New France in 1534.

The Dutch Republic of the Netherlands founded the colony of New Netherland in North America (present-day region of the states of Connecticut, Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and surrounding environs) in 1614, and Sweden had established their own, New Sweden, in part of modern-day Delaware by 1638. Other nations such as Russia, Germany, and Scotland also attempted to establish themselves in the New World without success.

The wealth Spain acquired from their colonies and the enslavement and sale of indigenous people encouraged England to establish their own presence in the New World. The first two colonies – Popham and Roanoke Colony – failed but the third, Jamestown, founded in Virginia in 1607, succeeded. The Plymouth colony followed, founded in 1620 in Massachusetts and, afterwards, the basic regions of European control in the Americas, in spite of periodic conflicts, were established until the French and Indian War (1754-1763) which resulted in significant reformation and English control of the entire eastern seaboard of the modern-day United States.

The colonization is recognized as initiating the Columbian Exchange, a modern-day term coined in 1972 by the historian Alfred W. Crosby, jr. of the University of Texas at Austin, referring to the cross-cultural transmission of animals, crops, disease, technology, cultural values, and human populations between the Americas, West Africa, and Europe.

Among the most significant plants introduced by the indigenous people to the colonists of North America was tobacco which, because it was labor-intensive and required considerable arable land to cultivate, resulted in hostilities between the Europeans and natives as more and more land was taken, deforestation as land was cleared, and the institutionalization of slavery by c. 1640, already established by the Spanish in Central and South America earlier as part of the feudal encomienda system of forced labor.

The history of the conquest and colonization of the Americas was later written by the victors, which cast their efforts in a noble light in the interests of exploration, civilization, and conversion of the indigenous people to Christianity. In the modern era, this narrative has been challenged and initiatives proposed to recognize the cultural losses and human rights abuses of the Native Americans and West Africans by the European colonizers but, so far, nothing significant has come of these efforts.

Columbus, Portugal, & the Spanish Conquest

Trade between Europe and Asia had been ongoing since 130 BCE when the Han Dynasty of China (202 BCE - 220 CE) opened the routes known in the modern day as the Silk Road. Although there were contentions over these routes through the years, and different monarchies or tribes took control of them in whole or in part, they remained open, and goods traveled back and forth along them until the fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottomans in 1453; afterwards, the Ottoman Empire closed the Silk Road to the West.

Europeans had grown used to the items from Asia, however, and so began to look for other routes to the East. Columbus believed he could find a new passage by sailing west and received funding for his expedition by Ferdinand II and Isabella I of Spain, setting out on his first voyage in 1492. Columbus landed in the Bahamas, believing the first island he claimed for Spain to be a part of a chain just off the coast of China. His next three voyages would include efforts at finding a sea passage in the region leading to Asia, but, after his first, Spain was just as interested in colonization and exploitation of the New World as a new route to the East.

Columbus and his crew made the first voyage in three ships; he returned in 1493 at the head of 17 ships full of colonists, soldiers, priests, and large Mastiffs to intimidate the native people. Columbus, as per his agreement with Ferdinand and Isabella, became governor of the new colony and established the encomienda system whereby Spanish settlers marked out a sizeable tract of land and offered the Native Americans protection, primarily from themselves, in return for labor.

In 1500 Cabral claimed the region of modern-day Brazil, and a colony would be established there by 1530. The Portuguese had no more regard for the indigenous people of the region than Columbus had earlier and almost instantly enslaved them. Finding that the people had no immunity to European diseases and died quickly and also that they did not seem to be able to endure hard manual labor, they imported slaves from West Africa. By this time (c. 1540), between Columbus' efforts and Cabral's, an estimated 90% of the indigenous population was dead.

Columbus had promised Ferdinand and Isabella a wealth of gold from the New World which he had not delivered and so others were sent to find it. Hernán Cortés (l. 1485-1547) is among the most infamous of these, conquering the Aztec Empire of Mexico between 1519-1521 and sending his commander Pedro de Alvarado (l. c. 1485-1541) to subdue the Maya to the north in 1523; a mission which the earlier conquistador Cordoba had failed to accomplish and which would not be completed until 1697 when the conquistador Martín de Ursúa (l. 1653-1715) crushed the last of the Maya resistance.

By that time, the cultures of the Yucatec and Quiché (or K'iche') Maya had been destroyed or driven underground. The books and icons of the Maya of Yucatán, Mexico were burned by the bishop Diego de Landa at Mani in 1562, and the holy book of the Quiché, the Popol Vuh, written c. 1554-1558, states at the outset it is being written in secret to preserve what has already been lost to the Spanish conquerors.

The conquest continued elsewhere and in all directions as part of the ongoing European quest for gold, which eventually established Spanish claims from the present-day southern west regions of the United States through Central and South America. In the region of modern-day Venezuela, Francisco Pizarro (l. c. 1476-1541), conquered the Inca in 1532 and the last of their resistance was crushed by 1572. Once the indigenous people had been killed, sold into slavery, or otherwise removed, Spanish colonists established themselves on their lands.

France & the Netherlands

The colony of New France was founded in modern-day Canada by the French explorer Jacques Cartier (l. 1491-1557) in 1534. France would also claim land holdings in the regions of modern-day South America, the Caribbean, the state of Louisiana, and elsewhere. Cartier's mission, like Columbus', was to navigate a maritime passage to Asia and return to France with gold.

On his first voyage, he and his crew kidnapped two of the sons of an Iroquois chief, Donnacona. He returned in 1535 with three ships, the two sons (who had been allowed to be taken by their father in return for various goods), and plans for settlement which were fully implemented on his third voyage in 1541. He named the new territory Canada from an Iroquois word (Kanata) for “village”.

He was sure, based on what he thought Donnacona had said, that Canada was a land teeming with gold, and his reporting this to the French authorities (and finally kidnapping Donnacona so he could tell them himself) guaranteed more colonists and profiteers arriving in the region after 1542. The French were not interested in enslaving the indigenous people since they already had learned by this time that they did not make good slaves and found it more profitable to have the natives work for them in supplying animal furs and other goods to be sold in Europe.

The Dutch would also lay claim to parts of lower Canada, as well as the modern-day region of the Hudson River Valley in New York State, through the efforts of the Dutch East India Company which, like the others, was seeking a route to Asia (this elusive route, never found because it did not exist, came to be known as the Northwest Passage) and colonized North America along the way. The explorer Henry Hudson (Hendrick Hudson, l. c. 1565-1611) mapped and claimed the regions for the Dutch East India Company in 1609, and colonies would be established by 1614 with New Amsterdam (Manhattan) added in 1624.

Early English Colonies

England, impressed by the wealth Spain was able to acquire from the New World, considered establishing their own colonies there but, first, found it easier to have privateers (state-sponsored pirates) stop Spanish vessels returning from the Americas and seize their cargo, among them Sir Francis Drake (l. c. 1540-1596), known to the Spanish as “the Dragon” for the ferocity of his attacks on settlements in Panama and continual strikes against their ships.

The English understood, however, that it would be more efficient and effective to launch ships against the Spanish from the coasts of the Americas than their own and so Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603), who had funded Drake's missions, tasked her friend and confidante Sir Walter Raleigh (l. c. 1552-1618) with sending an expedition to claim any lands in the Americas not yet under the flag of a European nation.

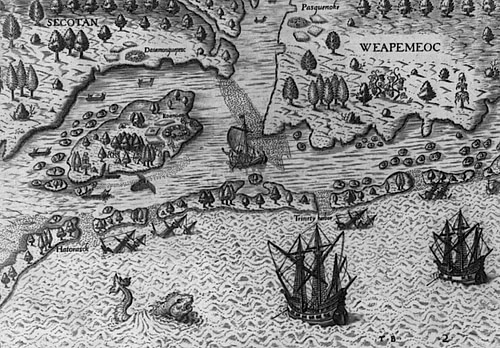

Raleigh placed the captains Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe in charge of two ships and sent them off in 1584 (known as the Amadas-Barlowe Expedition) to find a suitable spot. They returned later that year and reported to Raleigh who told Elizabeth that they had found a bountiful land, filled with friendly natives, which he called Virginia in honor of Elizabeth, the virgin queen.

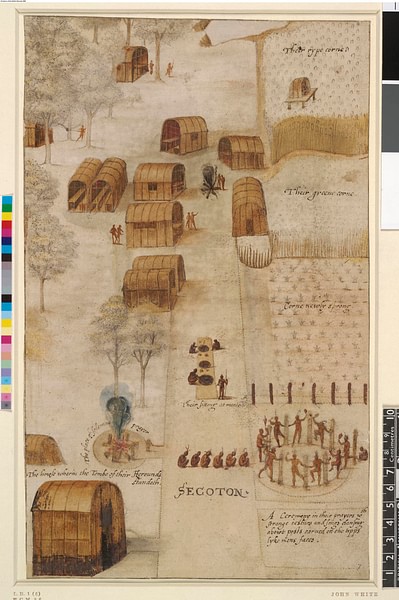

The first settlement was established in 1585 on Roanoke Island, because the ships could not reach the mainland owing to a storm, under the leadership of Ralph Lane (d. 1603). The indigenous people were, at first, friendly, but when the colonists' supplies grew low and the natives had tired of helping them for nothing in return, Lane attacked and killed their chief. Afterwards, low on food and outnumbered by the natives, the colonists accepted a ride back home with Francis Drake who was passing by after another raid on the Spanish.

A second expedition was sent in 1587 under a John White who brought his family along with 117 settlers, mostly families, all of whom were promised land. As before, the colonists began to run out of food, but this time the indigenous people were not so friendly, and no help was offered. White returned to England for supplies and, owing to bad weather and other delays, did not return until 1590 when he found all the colonists gone, giving Roanoke the epithet of “the lost colony”.

One of the causes for the delay which prevented White from returning sooner was the threat of Spanish ships which were under the directive to end the privateering of Englishmen like Drake. Deciding to strike at the source of the trouble, Spain assembled its entire armada – 132 ships carrying 17,000 soldiers and 7,000 sailors – for an invasion of England in 1588. They were met by Drake and others who sent flaming ships into their midst, firing their boats, and a sudden storm then broke their formations; only half of the fleet managed to return to Spain.

Elizabeth I died in 1603, and the throne was assumed by James VI of Scotland who became James I of England (r. 1603-1625). With the Spanish threat removed, new plans were underway to colonize the New World and two expeditions were launched in 1606; one funded by the London Company (also known as the Virginia Company) and the other by the Plymouth Company, both of which received charters from King James I to establish colonies in separate regions of North America. The Plymouth Company's expedition would found the Popham Colony in the region of modern-day Maine in 1607, but it failed after a little over a year. The Virginia Company's colony would become Jamestown, also founded in 1607, which struggled but survived to become the first permanent English colony in North America.

Conclusion

The Jamestown colony barely survived the first few years, losing 80% of its population in only a few months, primarily because those who made up the expedition were either upper-class aristocrats who refused to work for their food or lower-class laborers who had no skill in farming. The colony was saved first by Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631), a soldier, sailor, and adventurer who famously pronounced “he who does not work, shall not eat” and managed to organize the survivors to fend for themselves while also establishing a cordial relationship with the indigenous people of the Powhatan tribe, without whose help the colonists would have starved to death.

Smith returned to England in 1609, and the colony suffered from his absence, enduring what is known as the Starving Time during which they resorted to cannibalism. A ship, the Sea Venture, was en route to bring them aid when it was blown off course and wrecked in Bermuda in 1609. With no help coming and no supplies, the colonists were going to abandon the settlement and return to England when, in 1610, ships arrived carrying supplies and the three men who would turn the colony's fortune's around: John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622, who would later marry the famous Pocahontas, l. c. 1596-1617), Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1585-1622, the future governor), and Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618).

De La Warr prevented the desperate colonists from leaving and organized the colony while Gates handled daily administration and Rolfe introduced a new seed blend of tobacco he felt would do well in the Virginian soil and be popular back in Europe. Rolfe was correct, and the tobacco crop not only saved the colony but encouraged others in England to come to the New World. The crop also, unfortunately, required extensive lands for cultivation for maximum profit and a later arrival, Sir Thomas Dale (l. c. 1560- 1619), orchestrated the removal of the Powhatan tribe. Indentured servitude provided the necessary labor for the crop at first but, when this proved problematic, was eventually replaced by institutionalized slavery.

In 1619, the House of Burgesses was first convened, the first assembly of Englishmen in North America to gather and establish laws. This event is traditionally recognized as the earliest expression of democracy in the New World, even though it has become clear that the Native American tribes had been practicing a democratic form of government for centuries prior to this date.

The success of Jamestown encouraged the founding of the Plymouth colony in 1620 by the Puritan Separatists under Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655) and William Bradford (l. 1590-1657) who characterized themselves as pilgrims seeking a holy land in which they could worship freely. Jamestown would eventually be abandoned and forgotten, but Plymouth colony, though it would only last until 1691, would live on in the national imagination, inspiring the images of grateful pilgrims and helpful natives as the foundational myth of what would become the United States of America.