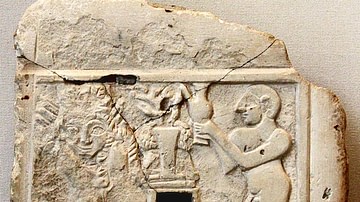

Enlil (also known as Ellil and Nunamnir) was the Sumerian god of the air in the Mesopotamian Pantheon but was more powerful than any other elemental deities and eventually was worshiped as King of the Gods. He is featured in a number of important Mesopotamian texts as the greatest of the gods after his father.

He was the son of the god of the heavens Anu (also known as An) and, with Anu and Enki (god of wisdom), formed a triad which governed the heavens, earth, and underworld or, alternately, the universe, sky and atmosphere, and earth. After Anu, Enlil was the most powerful of the Mesopotamian gods, keeper of the Tablets of Destiny which contained the fates of gods and humanity, and considered an unstoppable force whose decisions could not be questioned.

The city of Nippur was the central seat of Enlil's worship at the temple/ziggurat known as "the Mountain House" - described as "glistening" and magnificent in the hymn Enlil in the E-Kur - but he was also honored in Babylon and other cities. He was the only god with direct access to Anu, who controlled the universe, and was highly respected for this position, but at the same time, his decisions seem to be final without regard to Anu, and so it can seem unclear what Anu's influence over Enlil was.

Although his name translates as "Lord of Air," he was clearly considered much more than a sky god. He is referred to as 'Father of the Black-headed People' (the Sumerians) and 'Father of the Gods' in some inscriptions, but other ancient texts make clear that Enki conceived of creating human beings and the gods were either born of Anu and Uras (Heaven and Earth) or, according to the Babylonian Enuma Elish, from Apsu and Tiamat (Fresh and Salt Water) or their children Anshar and Kishar (also Heaven and Earth). Scholar Stephen Bertman tries to clarify Enlil's position, writing:

If Anu was the heavenly chairman of the board, Enlil was the heavenly corporation's CEO, or chief executive officer. His cosmic headquarters were based at Nippur. His executive assistant was his son Nuska. Enlil/Ellil was a family man, married to Ninlil (also called Sud), and with her he raised a brood that included - among others - the moon-god Nanna/Sin, the sun-god Utu-Shamash, the weather god Ishkur/Adad, and the love-goddess Inanna/Ishtar. (118)

Although that explanation may clarify somewhat, Enlil is also sometimes referred to as the son of Enki and Ninki (Lord and Lady Earth and not Enki, the god of wisdom) while Enki, the god of wisdom, is established as the twin brother of Ishkur/Adad, which would make him obviously another son of Enlil, which he was not.

Further, although Inanna is frequently depicted as a daughter of Enki, she is also mentioned as Enlil's child. All of these seeming contradictions stem from Mesopotamia's long history and the different cultures which adopted Sumerian gods and made them their own with additions and alterations to their stories. Sometimes these changes expand upon or continue older stories, but in various eras different scribes in ancient Mesopotamia simply rewrote the tales to suit their purposes.

Worship of Enlil dates from the Early Dynastic Period I (c. 2900-2800 BCE) at Nippur and firmly from the time of the Akkadian Empire (2334 - 2218 BCE) down until he was absorbed and assimilated into the god Marduk during the reign of Hammurabi of Babylon (1792-1750 BCE). Even after that time, however, he continued to be widely honored throughout Mesopotamia, and so it is not surprising that different stories, from different regions and various eras, should depict him with different characteristics and details.

He was among the oldest gods and counted as one of the Seven Divine Powers: Anu, Enki, Enlil, Inanna, Nanna, Ninhursag, Utu-Shamash. His importance as the supreme god for thousands of years is reflected in the roles he plays in Mesopotamian myths and his epithet Nunamnir, thought to mean "He Who is Respected."

Enlil & Ninlil

In the early myth known as Enlil and Ninlil, Enlil is seen as a young god living in the city of Nippur before the creation of human beings. Nippur is an urban center of the gods in this story and governed by divine law. Ninlil (also known as Sud) is a young and beautiful goddess who is attracted to Enlil as he is to her. Ninlil's mother, Nisaba (goddess of writing and scribe of the gods), cautions her against going to bathe in the river and encouraging the advances of young Enlil, warning her against the dangers of losing her virginity. Ninlil ignores this advice, however, goes to the river, and is seduced by Enlil. She becomes pregnant and gives birth to the moon god Nanna. Enlil must then go to Nisaba and ask for her daughter's hand in marriage.

Afterwards, as Enlil is walking through the city, he is arrested by the other gods for being ritually impure and exiled from the city to the underworld. The charge against him seems to have nothing to do with Ninlil's seduction, however. Ninlil is also arrested and exiled and follows him out of the gates but at some distance behind him. Enlil speaks to each of the keepers of the gates or important personages of the underworld instructing them not to tell Ninlil where he has gone if she should ask.

He then disguises himself as each one, and when Ninlil approaches and asks where Enlil has gone, he says he will not tell her. Ninlil offers him sex for information, and he agrees although each time this happens, he tells her nothing. In this way, they give birth to the deities Nergal, Ninazu, and Enbilulu, gods of war, healing, and canals, respectively. In other myths, however, these three gods have different parents and Ninazu, especially, is more commonly known as the son of Gula, goddess of healing. The hero-god Ninurta is also sometimes represented as one of their children though, in the best-known myths, he is the son of Ninhursag and Enlil.

The story ends in praise to Enlil for his virility, and the myth is thought to celebrate the fertility of the earth. The two young deities, defying the laws that would keep them apart, join together to produce life, and even when they are banished to the underworld, they cannot be separated and continue the creative act. Enlil as the rebel who defies the laws of the gods to pursue his own desires changes in other myths into the authority who wields the power of divine law and whose judgments cannot be questioned.

Enlil & the Anzu Bird

In the Babylonian Myth of Anzu (early 2nd millennium BCE), Enlil is seen as the supreme god who holds the Tablets of Destiny, sacred objects which legitimized the rule of a supreme god and held the fates of the gods and humanity. Scholar E. A. Wallis Budge relates one version of the myth:

The Zu bird [also known as the Anzu], the symbol of storm and tempest, was a god of evil who waged war against Enlil, the holder of the "Tablets of Fate", whereby he ruled heaven and earth. Zu coveted this tablet and determined to take it and rule in his stead. Zu watched his opportunity and, one morning when Enlil had taken off his crown and set it down on a stand, and was washing his face with clean water, Zu snatched the Tablet from him and flew away with it into the mountains. Anu called on the gods to go out against Zu and take the Tablet from him but one and all refused and the affairs of heaven and earth fell into disorder. (111)

In this particular version of the myth, the hero Lugalbanda retrieves the tablets, while in others it is Ninurta or Marduk who are the champions. In each version, however, Enlil is shown as the legitimate king of the gods, authorized to act by the Tablets of Destiny and fully supported by the supreme god Anu. In this light, Enlil was viewed as the epitome of kingship, acting as a mediator between the higher powers and the mortal world. Even so, even Enlil could have a bad day and lose his patience as recorded in the myth of the Great Flood known as The Atrahasis.

The Atrahasis

In The Atrahasis (c. 17th century BCE), the elder gods live a life of leisure while forcing the younger gods to do all the work in maintaining the universe. The younger gods have no time for themselves, and so Enki proposes they make lesser creatures who will work for them. When they can find no suitable material to make these new beings from, the god We-llu (also known as llawela) volunteers to be sacrificed and is killed. The mother goddess Ninhursag then kneads his flesh, blood, and intelligence into clay to create 14 human beings: seven male and seven female.

These new creatures are placed on the earth and, at first, perform exactly as the gods had hoped; they do all the work in maintaining the land and provide worship and sacrifice to the gods in thanks for their lives. The creatures turn out to be exceptionally fertile, however, and soon there are hundreds and then thousands of them, and they keep multiplying and begin to become louder and louder and cause more and more problems among themselves.

Enlil finally cannot tolerate the noise anymore and decides to decrease their population. He sends a drought, a pestilence, and a famine upon the people, but each time they appeal to their creator Enki for help and he secretly informs them what to do to save themselves and return balance to the earth. Enlil cannot understand what is happening since somehow everything he sends against the creatures seems to simply help them multiply more abundantly, and so he decides to destroy them all in a great flood.

He convinces the other gods of the necessity of his plan and sets it in motion. Enki disagrees but can do nothing to change Enlil's decree once it has been made. Enki travels to earth to whisper to the sage Atrahasis about what is coming and tells him to build an ark and load two of every kind of animal into it to save them and himself. Atrahasis does as he is told, the flood comes, and life on earth is destroyed.

Enlil almost instantly regrets his decision, and the gods mourn the passing of their creatures, but none of them can do anything about the situation. Enki then tells Atrahasis to open the ark and make a sacrifice to the gods, and he does so. The sweet smell of the sacrifice reaches the heavens and Enlil, although only just upset about his flood, is furious that a human somehow survived. He turns on Enki who explains himself and invites the gods to join him in accepting the sacrifice.

As they eat, Enki proposes a new plan by which they will create new creatures who will be less fertile and have shorter lifespans, and Enlil agrees. Human beings are created to experience infertility, mortality, and daily threats to their existence. Although Enki is regarded as the creator, since humanity was his idea, nothing could move ahead without Enlil's consent, and so he was regarded as the great father of men and women.

Worship & Assimilation with Marduk

Enlil continued to be worshiped up through the reign of Hammurabi when the Babylonian god Marduk, son of Enki, became supreme. Marduk, hero of the Enuma Elish, was represented as defeating the forces of chaos, creating human beings and the earth they lived on, and establishing law and agriculture. The most important qualities of Enlil (and some of Enki's) were absorbed into Marduk, who then became the king of the gods not only for the Babylonians but, as the son of Assur, of the Assyrians.

From the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) until Hammurabi's reign, Enlil was worshiped at his temple in Nippur, the most important religious site in southern Mesopotamia other than Eridu (associated with Enki). According to scholar Jeremy Black, Enlil was so powerful and awe-inspiring that "the other gods might not even look upon his splendour" (76). The hymn known as Enlil in the E-kur (also Enlil A) describes his temple at Nippur as dazzling. From Nippur, his worship spread north to Akkad and throughout Sumer, with temples at Kish, Lagash, Babylon, and other cities. Worship of Enlil, as with other Mesopotamian gods, focused on the temple-ziggurat and temple complex which served multiple purposes for the community.

There were no temple services, as one would understand them today, but the temple still served as an integral aspect of every city. People would worship Enlil by bringing offerings with supplications or in thanks for gifts given, and the god's statue and inner sanctum would be cared for by the high priest. As was customary throughout Mesopotamia and Egypt, none but the high priest could enter the presence of the god or commune with him in the temple, and most people's interactions with their deities were through private rituals at home or public festivals.

Once Enlil was absorbed into Marduk, his worship declined but he was still honored in shrines in many cities, and even in Babylon it was understood that Enlil and Anu had willingly conferred their power and blessings on Marduk. Enlil's temples were still active during the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (912-612 BCE) when the gods Assur, Marduk, and Nabu were considered the supreme deities. According to scholar Adam Stone, "Enlil's power was clearly remembered for even [these gods] were referred to as the 'Assyrian Enlil' or the 'Enlil of the gods'" (2).

After the fall of the Assyrian empire in 612 BCE, Enlil suffered the fate of many Mesopotamian gods associated with Assyrian rule: his statues were destroyed and his temples sacked. Gods who had managed to transcend their association with Assyria in the minds of the people, like Marduk, lived on, and in transferring Enlil's qualities to the younger god, Enlil survived under that name until c. 141 BCE, by which time veneration of Marduk had declined and Enlil was forgotten.