Enlil in the E-Kur (c. 2000 BCE) is a Sumerian hymn praising the sky god Enlil, his temple/ziggurat at Nippur, and his consort Ninlil, depicting all three in glowing terms and Enlil as a creator-god. The piece is highly regarded as an important work of Mesopotamian literature as well as for its influence on books of the Bible.

The hymn was almost certainly sung at festivals in ancient Mesopotamia in honor of Enlil whose temple complex at Nippur was among the most opulent in Sumer. Nippur was always regarded as a holy city, seat of Enlil's cult, and kings of the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE), Akkadian Period (2334-2218 BCE), and Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE) – as well as later monarchs – made it a priority among their building, renovation, and restoration projects.

The kings of the Ur III Period, beginning with Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) and his son Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE), paid special attention to Nippur as they claimed their authority to rule from Enlil and Ninlil and the poem is thought to date from the reign of Shulgi as similar works are also, including the poem Shulgi and Ninlil's Barge.

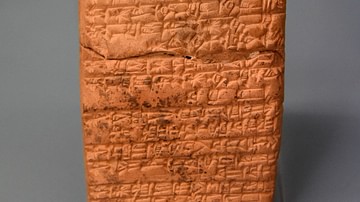

Enlil in the E-Kur (also known as Enlil A, Hymn to Enlil, and Hymn to the E-kur) was clearly popular based on the number of copies found at Nippur and elsewhere. The piece was included in the curriculum of the edubba ("House of Tablets"), the Mesopotamian scribal school, as part of the advanced course of study known as the Decad toward the end of a student's formal course of education.

The cuneiform tablets were found in fragments in the early 20th century, and the work was first translated and published between 1918-1928. Today it is among the most popular works of ancient Mesopotamian literature for its detailed description of the E-Kur (temple), its depiction of Enlil as the source of all creation, and the influence it is thought to have had on the later books of the Bible, especially the Book of Psalms.

Summary & Commentary

Enlil began as the Sumerian god of the air, son of An (Anu) the Lord of the Heavens, but eventually replaced his father as King of the Gods while also forming a divine triad with Anu and Enki, the god of wisdom. In some myths, Enlil seems subordinate to Anu or Enki or his consort Ninlil, but in most, he is the most powerful deity of the Mesopotamian pantheon, keeper of the Tablets of Destiny which held the fates of gods and humans, and the creator and preserver of universal order. He was worshipped from c. 2900 to c. 141 BCE.

Enlil in the E-kur addresses this vision of the god as all-powerful and steadily emphasizes his greatness and the splendor of his home in Nippur throughout, concluding with a final line of praise. Scholar Jeremy Black gives a brief summary of the progress of the text:

The structure alternates between third-person descriptions (1-64, 100-130) and direct addresses to the deity (65-99, 131-171). Images of righteousness (18-25), festivity (44-55), visual brilliance (65-73), awesomeness (74-83), fatefulness (100-108), and justice (139-155), are dominant for much of the poem. In one extraordinary passage (109-130), the poet tries to imagine the world without Enlil: he concludes that nothing at all would exist. (320-321)

The god is also referenced as a "faithful shepherd" (line 93) and the "prince of heaven" (line 100) which, taken with other epithets and attributes given throughout, have led some scholars to cite the work as influencing the Psalms of the Bible (notably the famous Psalm 23 beginning with "The Lord is my shepherd ...") as well as other biblical books including parts of Isaiah, the Gospels, and the Book of Revelation.

Text

The following is taken from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by Jeremy Black et al., and from The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, translated by the same. Ellipses indicate missing lines or words, and question marks suggest an alternate translation of a word. The hymn addresses Enlil by a number of names, including Nunamnir and Great Mountain while his temple is referenced as the Mountain House, among other terms including Dur-an-ki, the meeting place of heaven and earth. The goddess Ninhursag is given here as Nintu, and Enlil's son, Nuska, is also mentioned. Nippur is given here as Nibru, and the abzu refers to the watery realm beneath the holy city of Eridu, regarded as a source of life in some myths.

1-9: Enlil's commands are by far the loftiest, his words are holy, his utterances are immutable! The fate he decides is everlasting, his glance makes the mountains anxious, his ... reaches (?) into the interior of the mountains. All the gods of the earth bow down to Father Enlil, who sits comfortably on the holy dais, the lofty dais to Nunamnir, whose lordship and prince ship are most perfect. The Anuna gods enter before him and obey his instructions faithfully.

10-17: The mighty lord, the greatest in heaven and earth, the knowledgeable judge, the wise one of wide-ranging wisdom, has taken his seat in the Dur-an-ki, and made the Ki-ur, the great place, resplendent with majesty. He has taken up residence in Nibru, the lofty bond (?) between heaven and earth. The front of the city is laden with terrible fearsomeness and radiance, its back is such that even the mightiest god does not dare to attack, and its interior is the blade of a sharp dagger, a blade of catastrophe. For the rebel lands it is a snare, a trap, a net.

18-25: It cuts short the life of those who speak too mightily. It permits no evil word to be spoken in judgement (?). ..., deception, inimical speech, hostility, impropriety, ill-treatment, wickedness, wrongdoing, looking askance (?), violence, slandering, arrogance, licentious speech (?), egotism and boasting are abominations not tolerated within the city.

26-34: The borders of Nibru form a great net, within which the hurin eagle spreads wide its talons. The evil or wicked man does not escape its grasp. In this city endowed with steadfastness, for which righteousness and justice have been made a lasting possession, and which is clothed (?) in pure clothing on the quay, the younger brother honours the older brother and treats him with human dignity; people pay attention to a father's word and submit themselves to his protection; the child behaves humbly and modestly towards his mother and attains a ripe old age.

35-43: In the city, the holy settlement of Enlil, in Nibru, the beloved shrine of father Great Mountain, he has made the dais of abundance, the E-kur, the shining temple, rise from the soil; he has made it grow on pure land as high as a towering mountain. Its prince, the Great Mountain, Father Enlil, has taken his seat on the dais of the E-kur, the lofty shrine. No god can cause harm to the temple's divine powers. Its holy hand-washing rites are everlasting like the earth. Its divine powers are the divine powers of the abzu: no one can look upon them.

44-55: Its interior is a wide sea which knows no horizon. In its ... glistening as a banner (?), the bonds and ancient divine powers are made perfect. Its words are prayers, its incantations are supplications. Its word is a favourable omen ..., its rites are most precious. At the festivals, there is plenty of fat and cream; they are full of abundance. Its divine plans bring joy and rejoicing, its verdicts are great. Daily there is a great festival, and at the end of the day there is an abundant harvest. The temple of Enlil is a mountain of abundance; to reach out, to look with greedy eyes, to seize are abominations in it.

56-64: The lagar priests of this temple whose lord has grown together with it are expert in blessing; its gudu priests of the abzu are suited for your lustration rites; its nuec priests are perfect in the holy prayers. Its great farmer is the good shepherd of the Land, who was born vigorous on a propitious day. The farmer, suited for the broad fields, comes with rich offerings; he does not ... into the shining E-kur.

65-73: Enlil, when you marked out the holy settlements, you also built Nibru, your own city. You (?) ... the Ki-ur, the mountain, your pure place. You founded it in the Dur-an-ki, in the middle of the four quarters of the earth. Its soil is the life of the Land, and the life of all the foreign countries. Its brickwork is red gold, its foundation is lapis lazuli. You made it glisten on high in Sumer as if it were the horns of a wild bull. It makes all the foreign countries tremble with fear. At its great festivals, the people pass their time in abundance.

74-83: Enlil, holy Urac is favoured with beauty for you; you are greatly suited for the abzu, the holy throne; you refresh yourself in the deep underworld, the holy chamber. Your presence spreads awesomeness over the E-kur, the shining temple, the lofty dwelling. Its fearsomeness and radiance reach up to heaven, its shadow stretches over all the foreign lands, and its crenellation reaches up to the midst of heaven. All lords and sovereigns regularly supply holy offerings there, approaching Enlil with prayers and supplications.

84-92: Enlil, if you look upon the shepherd favourably, if you elevate the one truly called in the Land, then the foreign countries are in his hands, the foreign countries are at his feet! Even the most distant foreign countries submit to him. He will then cause enormous incomes and heavy tributes, as if they were cool water, to reach the treasury. In the great courtyard he will supply offerings regularly. Into the E-kur, the shining temple, he will bring (?) ...

93-99: Enlil, faithful shepherd of the teeming multitudes, herdsman, leader of all living creatures, has manifested his rank of great prince, adorning himself with the holy crown. As the Wind of the Mountain (?) occupied the dais, he spanned the sky as the rainbow. Like a floating cloud, he moved alone (?).

100-108: He alone is the prince of heaven, the dragon of the earth. The lofty god of the Anuna himself determines the fates. No god can look upon him. His great minister and commander Nuska learns his commands and his intentions from him, consults with him and then executes his far-reaching instructions on his behalf. He prays to him with holy prayers (?) and divine powers (?).

109-123: Without the Great Mountain Enlil, no city would be built, no settlement would be founded; no cow-pen would be built, no sheepfold would be established; no king would be elevated, no lord would be given birth; no high priest or priestess would perform extispicy; soldiers would have no generals or captains; no carp-filled waters would ... the rivers at their peak; the carp would not ... come straight up (?) from the sea, they would not dart about. The sea would not produce all its heavy treasure, no freshwater fish would lay eggs in the reedbeds, no bird of the sky would build nests in the spacious land; in the sky the thick clouds would not open their mouths; on the fields, dappled grain would not fill the arable lands, vegetation would not grow lushly on the plain; in the gardens, the spreading trees of the mountain would not yield fruits.

124-130: Without the Great Mountain, Enlil, Nintu would not kill, she would not strike dead; no cow would drop its calf in the cattle-pen, no ewe would bring forth ... lamb in its sheepfold; the living creatures which multiply by themselves would not lie down in their ...; the four-legged animals would not propagate, they would not mate.

131-138: Enlil, your ingenuity takes one's breath away! By its nature it is like entangled threads which cannot be unraveled, crossed threads which the eye cannot follow. Your divinity can be relied on. You are your own counsellor and adviser; you are a lord on your own. Who can comprehend your actions? No divine powers are as resplendent as yours. No god can look you in the face.

139-155: You, Enlil, are lord, god, king. You are a judge who makes decisions about heaven and earth. Your lofty word is as heavy as heaven, and there is no one who can lift it. The Anuna gods ... at your word. Your word is weighty in heaven, a foundation on the earth. In the heavens, it is a great ..., reaching up to the sky. On the earth it is a foundation which cannot be destroyed. When it relates to the heavens, it brings abundance: abundance will pour from the heavens. When it relates to the earth, it brings prosperity: the earth will produce prosperity. Your word means flax, your word means grain. Your word means the early flooding, the life of the lands. It makes the living creatures, the animals (?) which copulate and breathe joyfully in the greenery. You, Enlil, the good shepherd, know their ways (?). ... the sparkling stars.

156-166: You married Ninlil, the holy consort, whose words are of the heart, her of noble countenance in a holy ma garment, her of beautiful shape and limbs, the trustworthy lady of your choice. Covered with allure, the lady who knows what is fitting for the E-kur, whose words of advice are perfect, whose words bring comfort like fine oil for the heart, who shares the holy throne, the pure throne with you, she takes counsel and discusses matters with you. You decide the fates together at the place facing the sunrise. Ninlil, the lady of heaven and earth, the lady of all the lands, is honoured in the praise of the Great Mountain.

167-171: Prominent one whose words are well established, whose command and support are things which are immutable, whose utterances take precedence, whose plans are firm words, Great Mountain, Father Enlil, your praise is sublime

Conclusion

The hymn ends with a final praise for Enlil, departing from the tradition of praising Nisaba, the goddess of writing, at the conclusion of a written work, to emphasize the god's greatness. The central message of Enlil in the E-kur, in fact, is summed up in lines 167-171 as the earlier praise lavished on his temple only has meaning because Enlil was thought to reside there. His home is praised because his presence elevates it and, to provide him with a residence worthy of that elevation, no expense was spared in the E-kur's construction and ornamentation. Black comments:

In Sumerian cosmology, Enlil's sanctuary Dur-an-Ki was conceptualized as the bond between heaven and earth – which is what the name itself signifies. Its great stepped tower, still prominent in the desert landscape today, must have been a dominant, awe-inspiring landmark in ancient times too. (321)

The hymn's praise of the temple would have worked as a mirror of the structure itself, carefully composed to elevate the souls of its audience just as the building complex did. Enlil in the E-kur, sung at festivals, would have reminded the people – just as the towering ziggurat did – that, whatever challenges or struggles they were contending with, their god was in control, guiding and helping them.