The concept of a curse laid on a tomb or gravesite is best known from ancient Egypt but the practice was quite common in other civilizations of antiquity. The tomb or grave was the eternal home of the physical remains of the deceased to which his or her soul could return at will, furnished with all of the keepsakes, tools, food and drink, and various objects the dead person would want or need in the next life. Many of these tombs, therefore (especially of the upper class and nobility) were literal treasure troves and attracted the attention of robbers.

Further, people who could not afford to bury their dead loved one – or did not want to spend the money – might secretly inter them in someone else's grave or someone who could not afford a tombstone might just steal one already used, scrape off the previous person's name, and use it for their own purposes. To prevent either of these violations of a grave, curses warning of dire consequences for any who disturbed the tomb – as well as fines to be imposed by authorities – were often included in epitaphs.

Examples of curse-fine epitaphs range from ancient China through Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, and Britain and a significant number – outside of Egypt – have been found in Anatolia (modern Turkey). Anatolia – especially the region of Cilicia – was long associated with piracy and so it is likely that the preponderance of curse-fine epitaphs in that region was a reaction to the criminal element and a necessary precaution against tomb robbery. Although studies of these Anatolian epitaphs show that all nationalities used them, as well as different religions (there was a large Jewish community in Anatolia), most of those which have survived are Greek. This is because of the many Greek colonies in the region and their conception of the afterlife.

Greek Afterlife

The ancient Greeks believed that the soul of the individual survived bodily death and went on to an afterlife. After death, the soul was judged by Aeacus, Minos, and Rhadamanthys, the three judges of the underworld, and sent to the realm it deserved based on the deeds done in life and the mercy of the judges. The souls of the wicked were sent to Tartarus, those of ordinary people – neither particularly good or evil – went to the Asphodel Meadows, those wounded by love went to the Fields of Mourning, and those who excelled in a virtuous life were directed to the Elysian Fields in which there was also the Isles of the Blessed. In whichever of these realms the soul wound up, its continued existence and prosperity depended on the memory of the living. The departed person's friends and relatives needed to remember them in order to keep their soul strong and vibrant.

The tomb or grave was not only the home for the deceased's remains and personal property but a visceral reminder of who they had been in life and, of course, that they had existed and were worthy of remembrance. To desecrate someone's tomb was to defile their memory, and if the tomb were vandalized severely enough or the gravestone actually stolen, the soul's welfare in the afterlife could be jeopardized. Scholar Andreas Vourloumis comments:

One major concern that has occupied humans regarding death is of course to be remembered after they pass away but also to be buried properly so their soul can rest and continue her course in another place…There is a plethora of funerary imprecations/prohibitions on epitaphs as an effort for the protection of the grave; those are inscribed publicly on gravestones by the owners of the grave in order to warn any potential violators. (2)

The grave needed to remain intact and undisturbed in order for the soul to be at peace in the afterlife and, if it was not, the consequences could be dire not only for that soul but for the relatives of the deceased who still lived. A spirit troubled by the desecration of its grave could return to haunt the living, causing all kinds of grief from impairments in physical and mental health to financial difficulties and even death. In order to keep the spirit happy – both for its own sake and that of the living – curses and fines to warn of desecrators were made explicit in epitaphs.

Greek Curses & Fines

Greek curses were considered a guarantee for justice, in this life or the next, as they invoked the gods for protection of the innocent and just while promising punishment for transgressors. These curses were certainly not limited to gravesites and could be placed anywhere via the construct known as the Curse Tablet as explained by scholar H. S. Versnel:

A curse is a wish that evil may befall a person or persons. Within this broad definition several different types can be distinguished, according to setting, motive, and condition. The most direct curses are maledictions inspired by feelings of hatred and lacking any explicit religious, moral, or legal legitimation. This category is exemplarily represented by the so-called curse tablets (Greek: katadesmos; Latin: defixio), thin lead sheets inscribed with maledictions intended to influence the actions or welfare of persons. (Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization, 201)

These curses most often took the form of stipulations such as “If someone should move my gravestone (or boundary stone or whatever) may they be cursed in such-and-such a manner and I call upon the gods (specific gods are mentioned depending on the situation called for) to bear witness and take my side.” As noted, people felt they could depend on such curses as deterrents but, just to be safe, criminal prosecution for transgressions was also made clear as a threat to grave robbers. In ancient Athens, if one were convicted of robbing a tomb, one was fined, and this fine was not cheap. Scholar Danielle S. Allen writes:

The cost of an adult male's food for a year was, on estimate, 36 drachmae, and the daily wage for an unskilled laborer at the end of the fourth century was 1.5 drachma so the power to fine to the tune of 10 and 50 drachmas was consequential…even a relatively minor court case could carry a penalty of up to 1000 drachmae. (4)

The fine was sometimes included in the epitaph by the owner of the grave but, if not, it was decided in court. There was no set fine on the books to which a judge could refer but, rather, the Athenian court would impose whatever punishment they agreed was just depending on the crime and the accused's situation. Even substantial fines or the wrath of the gods, however, could not deter graverobbers - in any ancient civilization - and for the simple reason that the rewards outweighed the risks. There was a fortune to be found in sometimes even a modest grave and, if one could set aside one's belief in the gods and their justice, all one had to do was not get caught.

The Cult of Cybele & Anatolian Graves

Ignoring the gods was no easy feat, however, as they were not only invoked in curses but their images were often set up as statues in and around burial sites. The Greeks who settled in Anatolia brought their beliefs with them but, in time, these combined with the religion of the indigenous people. The ancient Luwians and Hatti who had been living in the region since c. 2500 BCE worshipped a mother goddess who was adopted by the Phrygians (c. 1200-700 BCE) and known simply as Matar (mother) but better known by her epithet Kybeleia (mountain) or Cybele. Her cult center was in Pessinus, Phrygia (central Anatolia) and she was worshipped in the Anatolian kingdom of Lydia, along the coast, and elsewhere in the region.

Cybele was a fertility goddess but was also responsible for people's health and general well-being, protecting them in times of large-scale trouble (such as war or famine) as well as personal difficulties. Her consort was the dying-and-reviving vegetation god Attis and her cult encouraged a belief in eternal life after death and so emphasized the importance of protecting graves and tombs.

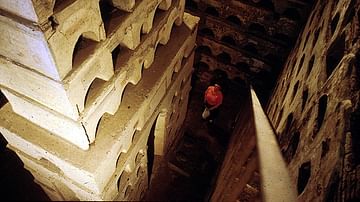

Statues of Cybele, sometimes accompanied by a lion or other animals symbolizing strength, were placed in shrines which were used to delineate a certain area or district from another. Cybele's statues were erected between buildings, for example, to make clear that one building's business was distinct from that of the other and between properties for the same purpose. Cybele's image was not just a reminder to respect other people's space but a powerful liminal demarcation which prohibited people from crossing from one area to another without good reason - and that would mean “without meaning to do good” - to the other person. In this same way, Cybele's shrines were set up outside of tombs and graves and, according to scholar Sharon R. Steadman, in doing so “the Phrygians created sacred space to mark the boundary between the living and the dead” (572).

In the same way that Cybele stood guard over people's farmlands, homes, and businesses, she watched over their graves and made sure they remained pristine. If, for some reason, she was distracted or otherwise engaged when a tomb robber showed up, however, there were the same type of curses invoked in epitaphs and the threat of fines as observed in Ancient Greece.

Anatolian Curses & Graves

The Anatolian curses followed the Greek paradigm and almost always fall under the modern-day definition of a “conditional curse” as explained by H. S. Versnel:

Conditional curses (imprecations) damn the unknown persons who dare to trespass against certain stipulated sacred or secular laws, prescriptions, and treaties. They are prevalent in the public domain and are expressed by the community through its representatives (magistrates, priests). The characteristic combination of curse and prayer [is a feature they share in common with judicial prayer]. The culprit thus found himself in the position of a man guilty of sacrilege and so the legal powers could enforce their rights even in cases where only the gods could help. (Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization, 201)

Even these threats by Cybele and court action did not deter grave robbers and a description of the contents of an Anatolian grave in Lydia gives a good idea why. Scholar Elizabeth Baugham writes:

Lydian grave offerings were not specific to certain burial types. The same kinds of goods are found in all types of Lydian graves, and most frequent are items of adornment and implements of banqueting. Often it is clear that the dead were laid to rest wearing jewelry and other finery [as in the case of] the untouched burial of a young “bride” in a sarcophagus within a Necropolis chamber: the find locations indicated that she wore gold fillets in her hair, gold earrings and a beaded necklace, a gold ring decorated with a lion, and a garment sewn with gold appliqué plaques. Although little skeletal evidence from Lydian graves has been analyzed, it is not likely that such jewelry was limited to female burials. Many other Necropolis tombs and looted tumuli have yielded necklaces, rings, earrings, bracelets, pins, brooches, and clothing ornaments. These items are often made of gold but glass and colored stones like onyx and agate were also used. (6)

To protect these treasures, curses and fines in epitaphs were quite explicit. They had to carry enough of a threat to at least make the potential robber think twice about the risk they were taking in disturbing the grave. The following are some examples provided by the work of Andreas Vourloumis:

Anatolian tombstone, provenance unknown, c. 154 CE: “Whoever shall cut a piece of this monument, may he place his children dead in the same way.” (8)

Anatolian tombstone, date unknown: “In this grave, unless I myself allow while still alive or order by will, if someone else brings in and buries someone, he will pay my beloved city 5000 denari in fine and will be answerable for grave robbing.” (10)

Anatolian tombstone found in Lycia, Roman Imperial Period: “Anna, along with her son Hieron, on account of her son Polemon, built this monument; if somebody transfer of convey these monuments, may he be destroyed along with his offspring.” (6)

Vourloumis notes how curses involving threats to a robber's children were considered particularly effective since one was not only risking one's own life but also theirs. Further, since the sins of the father were visited on their sons – as per Mesopotamian tradition long before the concept appears in the Bible (Exodus 20, Numbers 14, etc) – tomb robbers were risking not only the future health and happiness of their children but of their children's children.

Still, as Vourloumis also notes, even this was not enough of a deterrent since one's present need would supersede any other considerations:

Marble, as a raw material, was very expensive in antiquity and the plunder of a funerary stele was a constant phenomenon. The existent inscription of a stolen stele was scraped off thoroughly and a new text inscribed. (2)

This was an especially appalling crime because it erased the person's memory from his or her final resting place. To take someone's tombstone was to remove any trace of who they had been and what they had meant to others while they lived. Vourloumis writes:

The removal of a funerary stele was considered by Greeks and [later] Christians as the most severe insult for the dead and his grave, given that the stele was the most characteristic element of his identity. (2)

If a marble monument was stolen by an individual for private use, this was even more appalling since they clearly understood the importance of the stele as they would use it for the same purpose. Most likely, though, most were removed by thieves who then sold them to merchants who would trade them elsewhere or by pirates. Anatolia was associated with piracy from at least the time of the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BCE) and probably before. The piratical activity of the Lukka people of Anatolia is dated to Akhenaten's reign because he wrote to another king complaining of it. The Cilician pirates are the best-known of the region whose network ran throughout Anatolia, most likely from the southern coast of Cilicia up through the northern territories once held by the Lukka.

Conclusion

Records of convictions and punishments of tomb robbers in Anatolia is nowhere near as comprehensive as other regions, such as Egypt, owing to its history. Anatolia was repeatedly conquered and divided into separate kingdoms by other nations (the Akkadians, Hittites, Assyrians, Phrygians Persians, Alexander the Great, the Seleucids, Ptolemies, Rome, Armenians, Byzantines, and Muslim Caliphates) and few cared much for the records of the previous inhabitants.

It is likely, however, that efforts to curtail tomb-robbing followed a similar pattern to that of ancient Egypt. When the government and economy was stable, graves were still robbed but nearly as often or as brazenly as when either was in decline or weak. When the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) was steadily crumbling toward the end, thieves were more concerned about how they were going to feed their families than any curses or what the law might do to them.

Egyptian court records from c. 1110 BCE, in fact, make clear that law enforcement and court scribes could easily be bribed and some of the most shameless tomb robbers, men who had done irreversible damage to the tombs way beyond what was necessary for theft, often went free after a brief confinement (Lewis, 256-257). In Anatolia, the paradigm was probably the same in that people will always try to get away with whatever they can to serve their own self-interests and no number of curses, however dire, or threats of fine, however steep, have ever, or will ever, change that.