NOTE:

This article has now become the definition of Caracalla. Even though it is now a duplicate entry we're keeping it for all those who have linked to it.

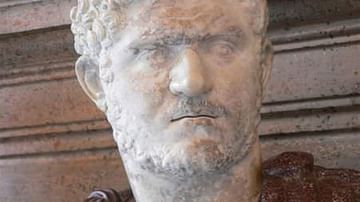

The emperor Caracalla was born Lucius Septimius Bassianus on the 4 of April, 188, in Lugdunum (Lyon), where his father Septimius Severus was serving as the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis during the last years of the emperor Commodus. When Caracalla was seven, his name was changed to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. This was done because of the wish of his father, now emperor to link the new Severan dynasty with the previous Antonine one. The name 'Caracalla' was considered a nickname, and referred to a type of cloak that the emperor wore (the nickname was originally used pejoratively, and was never an official name of the emperor). At the time his name was changed, Caracalla became the official heir of his father, and in 198, at the age of ten, he was designated co-ruler with Severus (albeit a very junior co-ruler!).

From an early age, Caracalla was constantly in conflict with his brother Geta, who was only 11 months younger than him. At the age of 14, Caracalla was married to the daughter of Severus' close friend Plautianus, Fulvia Plautilla, but this arranged marriage was not a happy one and Caracalla despised his new wife (Dio 77.3.1 states that she was a 'shameless creature'). While the marriage produced a single daughter, it came to an end when in 205 Plautianus was accused and convicted of treason, then executed. Plautilla was exiled and later put to death upon Caracalla's accession (Dio 77.5.3).

In the year 208, Septimius Severus, upon hearing of troubles in Britain, thought it a good opportunity to not only campaign there, but to take both of his sons with him as they were living libertine lifestyles in the city of Rome. Campaigning, Severus thought, would give both boys exposure to the realities of rule, thus providing experience for them which they could use upon succeeding their father. While in Britain, Geta was supposedly put in charge of civil administration there, while Caracalla and his father campaigned in Scotland. While Caracalla did acquire some valuable experience in military matters, he seems to have revealed an even darker side of his personality, and according to Dio tried on at least one occasion to kill his father so that he could become emperor. It was unsuccessful, and Severus later admonished his son, leaving him a sword within his son's reach challenging him to finish the job that he botched earlier (Dio 77.14.1-7). Caracalla backed down, but according to Herodian was constantly trying to convince Severus' doctors to hasten the dying emperor's demise (3.15.2). In any case, the emperor died at Ebaracum in February 211. Severus' last advice to both Caracalla and Geta was to 'Be good to each other, enrich the army, and damn the rest' (Dio 77.15.2).

So in 211 Caracalla became emperor along with his younger brother Geta. The relationship between the two did not resemble the loving one of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus fifty years earlier, and it seems that both brothers were constantly conspiring against each other so that one of them could become sole emperor. When the two did try to make decisions together, they constantly bickered, disagreeing on everything from political appointments to legal decisions. Indeed, according to Herodian, things got so bad between the two brothers that, not only did they divide the imperial palace up between them and try to convince each other's cooks to drop poison into the others food, it was proposed that the empire be divided up between the two into eastern and western parts. It was only the intervention of the boys' mother, Julia Domna, that this plan was not realized (Herodian 4.3.4-9).

Nevertheless, Caracalla resolved to be rid of his brother. After a failed attempt to assassinate his brother on the Saturnalia (Dio 78.2), Caracalla arranged a meeting with his brother and mother in the imperial apartments, ostensibly to reconcile. Instead, upon appearing in his brother's room with centurions, Caracalla had his men murder Geta, who tried to hide in his mother's arms. Despite her shock and sorrow, Caracalla forbade his mother from even shedding tears over Geta (ibid.; Herodian 4.4). So by 212, Caracalla was sole emperor, and according to Dio, his brother's murder was followed by a purge of Geta's followers which totalled in roughly 20,000 deaths, including that of the former Praetorian Prefect Cilo, and the jurist Papinian (Dio 78.3-6). Caracalla, when explaining his actions to the Senate, asserted that he was defending himself from Geta, and rejected the idea that the concept of two emperors ruling the empire could work, declaring that

you must lay aside your differences of opinion in thought and in attitude and lead your lives in security, looking to one emperor alone. Jupiter, as he is himself sole ruler of the gods, thus gives to one ruler sole charge of mankind.

The Senate could do nothing but tremble before his words (Herodian 4.5).

Geta was duly damned from memory (damnatio memoriae), all references to him in public were erased, and it was considered a crime to mention his name.

CARACALLA AND THE ROMAN ARMY IN THE WEST

While Caracalla did not take his father's advice in being good to his brother, he certainly took to heart that he needed to keep the army happy. Indeed, Caracalla declared to his soldiers that:

I am one of you," he said, "and it is because of you alone that I care to live, in order that I may confer upon you many favours; for all the treasuries are yours." And he further said: "I pray to live with you, if possible, but if not, at any rate to die with you. For I do not fear death in any form, and it is my desire to end my days in warfare. There should a man die, or nowhere. (Dio 78.3.2).

He backed up his words with actions, and raised annual army pay, evidently by 50% (Herodian 4.4.7). In order to pay for this raise, Caracalla debased the coinage from a silver content of from about 58 to 50 percent. It should be noted, however, that while he did debase the coinage, this did not cause deflation, as those receiving the coin were willing to accept its basic value. Caracalla also created the new coin known as the antoninianus, which was supposed to be worth 2 denarii, to help pay for these army raises (although the actual silver content was only worth 1.5 denarii; Birley 1996, 221).Note

He backed up his words with actions, and raised annual army pay, evidently by 50% (Herodian 4.4.7). In order to pay for this raise, Caracalla debased the coinage from a silver content of from about 58 to 50 percent. It should be noted, however, that while he did debase the coinage, this did not cause deflation, as those receiving the coin were willing to accept its basic value. Caracalla also created the new coin known as the antoninianus, which was supposed to be worth 2 denarii, to help pay for these army raises (although the actual silver content was only worth 1.5 denarii; Birley 1996, 221).1 Moreover, he attempted to portray himself as a fellow soldier while on campaign, sharing in the army's labours, personally carrying legionary standards and even grinding his own flour and baking his own bread, as all Roman soldiers did. These actions made him wildly popular with the army.

During this time, military activity in Britain began to wind down. As the campaign in Britain had stalled by the end of Severus' reign, Caracalla thought it necessary to engage in a face-saving maneuver and end the campaign there, but not before essentially creating a protectorate in southern Scotland to keep an eye on native activities. This essentially not only ensured his father's legacy as a propagator imperii on the island, but also would justify Caracalla's adoption of the title Britannicus (Birley 1988, 180). Even so, the natives north of Hadrian's Wall and the 'protectorate' had probably by this time felt discretion to be the better part of valour as making trouble had only invited the Roman army into their lands. If this is the case, then the Severan campaigns in Scotland kept that area peaceful for the better part of a century (Breeze and Dobson 2000, 152). There is also a degree of debate over whether it was Severus or in fact Caracalla who was the one to split Britain into two provinces in order to prevent governors from having access to a large number of legions, thus tempting them to make a bid for the imperial throne.Note

Instead, upon leaving Rome in 213, Caracalla (who would spend the rest of his reign in the provinces) decided to campaign in Raetia and Upper Germany against the Alamanni. While it is not clear if these enemies were making trouble for the empire, Caracalla prepared for this campaign very thoroughly and it seems that this campaign may have been a pre-emptive strike or a chance for Caracalla to win military glory in his own right.Note In any case, it is important to state that there was no serious enemy activity on this frontier until two decades later, so the emperor may have made an important contribution to Rome's security there, and had legitimate claim to the title of Germanicus which he adopted after these campaigns. Southern writes that Caracalla's frontier policy in this region:

seems to have been a combination of open warfare and demonstrations of strength, followed by an organisation of the frontiers themselves. He may have paid subsidies to the tribes after his campaigns, and in other cases he stirred up one tribe against another to keep them occupied and their attentions diverted from Roman territory (Southern 2001, 53).

THE CONSTITUTIO ANTONINIANA

One of the most noteworthy (and debated) acts of Caracalla's reign is his Edict of 212 (the Constitutio Antoniniana), which awarded Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. The motives for this action are many. Propagandistically, this edict allowed Caracalla to portray himself as a more egalitarian emperor who believed that all free people of the empire should be citizens, thus creating a stronger sense of Roman identity amongst them (Southern 2001, 51-2; Potter 2004, 138-9). More practically, however, this edict meant that Caracalla could widen the base from which he could collect an increased inheritance tax (ibid). Indeed, Dio states that, as a result of the money he lavished on the army, a financial shortfall was created and the emperor needed money, thus necessitating this edict and the consequent cheapening of the citizenship.Note Moreover, the propaganda of equality was illusory, as instead of a hierarchy of citizens and non-citizens in the empire, the edict created a new class division of upper and lower classes (honestiores and humiliores), in which honestiores had greater legal rights and privileges, while humiliores had less legal protection and were subject to harsher punishments (Southern 2001, 52).

CARACALLA IN THE EAST

Simply put, Caracalla idolized Alexander the Great, and sought to emulate him (Dio 78.7-8). Consequently, he saw fit to campaign in the east as a way to accomplish such emulation. It is debatable whether or not such campaigns were necessary, as at this time Rome's major rival, the Parthian Empire, was involved in internal conflicts, and the Parthian Royal House was fighting among itself (Dio 78.12.2-3). Caracalla saw this, however, as an excuse to mount a campaign to make gains at the expense of the Parthians. He returned to Rome after his activities in Germany, summoned Abgar, the King of Edessa to the city and imprisoned him in the hopes of turning Edessa into a colony and use it as a base from which to launch an invasion of Parthia. He seems to have tried to have done the same with the king of Armenia, but encountered resistance from that land's population (Dio 78.12.1). When he arrived in the East in 215, Caracalla had little reason to justify an invasion of Parthia, as that empire's king, Vologaeses V, made a point to avoid any action that could be construed as a provocation. Leaving preparations for a campaign against Parthia to his general Theocritus, Caracalla visited Alexandria, ostensibly to pay respects to Alexander the Great at his tomb. He was first welcomed by the Alexandrians, but when he found out they were making jokes about the reasons he gave for the murder of his brother Geta, flew into a rage and had a large segment of the population massacred (Dio 78.2.2; Herodian 4.9.8).

Caracalla then moved east to the frontier in 216, and found that the situation was not as advantageous to Rome as it was previously. Vologaeses' brother Artabanus V had succeeded him, and managed to reinstate a degree of stability to Parthia. Caracalla's best option in this instance would have been a quick campaign to demonstrate Roman strength, but instead the emperor opted to offer his own hand in marriage to one of Artabanus' daughters. Artabanus' refused, seeing this as a rather lame attempt by Caracalla to lay claim to Parthia (Herodian 4.10.4-5; Dio 79.1). According to Herodian, Caracalla's behaviour was even more reprehensible: the emperor invited Artabanus and his household to meet to discuss a permanent peace. Upon meeting with the Parthian king and his retinue, who had put aside their weapons as a sign of good will, Caracalla ordered his forces to massacre them. Most of the Parthians present were killed, but Artabanus was able to escape with a few companions (Herodian 4.11.1-6).

Caracalla then campaigned in Media in 217, and was planning a further campaign when his treacherous and rash behaviour caught up with him. It seems that he made sport of ridiculing his Praetorian Prefect M. Opellius Macrinus, who had a great deal of experience in legal matters but next to none in affairs military (Herodian 4.12.1-3). Macrinus began to resent this, but Caracalla began to fear the man, especially after hearing of a prophecy that Macrinus would become emperor. Caracalla then began to move against his Prefect, but Macrinus got wind of this and, realizing he was in great danger, conspired to assassinate the emperor (Dio 79.4.1-2; Herodian 4.12.5). This he did on the road to Carrhae, when the emperor stopped his troops on the side of the road to relieve himself. Evidently, while Caracalla was in the midst of urinating, one of Macrinus' men fell upon him, ending the emperor's life (Dio 79.5; 4.13.1-5). Caracalla was 29 years old when he died. When the bulk of the army had heard of his end, they were enraged at the murder of the emperor whom they loved. Indeed, Macrinus' inability to placate the soldiers helped to play a part in his own demise, when his enemies offered Caracalla's cousin Elagabalus as Emperor in 218.

ASSESSMENT

Caracalla was one of the most unattractive individuals ever to become emperor of Rome. He was cruel, capricious, murderous, wilfully uncouth, and was lacking in any sort of filial loyalty save for that of his mother Julia Domna (who died shortly after his assassination)Note. This is certainly the picture given to us by both Dio and Herodian. While some of the information in these accounts might be embellished, they nevertheless shed light on the increasing trend of emperors depending more on the army, believing they could act in any way they wanted towards the rest of the population provided they keep the soldiers happy. This is not entirely the fault of Caracalla, as he was following the advice of his father and genuinely wanted to be seen as a soldier and conqueror in the vein of Alexander the Great rather than the 'philosopher king' that Marcus Aurelius embodied. While his military policies in the western empire may have contributed to that region's security for several years, his eastern policy was self-destructive and unnecessary. Had Caracalla followed the formula of Augustus and maintained a balance between keeping both the army and the upper echelons of Roman society happy, he may have been more successful. In any case, the third century would witness many emperors who took the tact that Caracalla had, and would overly depend on the support of the army for their regime at their own peril.