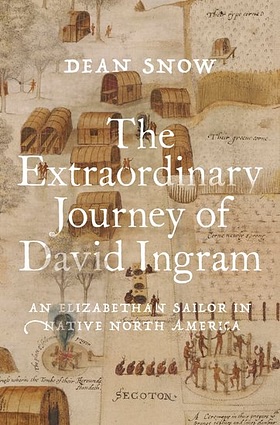

David Ingram was an Elizabethan explorer who famously walked over 3500 miles from Veracruz to New Brunswick in 1568-9. In 1567, Ingram had sailed down the Thames on the flagship Queen Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) had loaned John Hawkins for his third slaving expedition.

They had spent three months buying war captives in Africa and loading them as human cargo for illegal sale to colonists on the Spanish Main of the Caribbean. After arriving there in late March, they made several successful stops over the course of five months, then headed for home. Unfortunately it was hurricane season, and a huge storm drove the fleet into refuge at Veracruz, Mexico. A battle ensued, from which only two English ships escaped, leaving behind half the fleet's 400 men dead or captured. The overloaded Minion could not recross the Atlantic with so many survivors aboard, and 100 elected to take their chances ashore near Tampico. Of them, only David Ingram and two companions escaped death or capture.

Ingram's goal was to reach a friendly French outpost near modern Jacksonville, Florida. It took them over a month to hike from Tampico north to Galveston Bay, Texas, carrying bolts of fine cloth Hawkins had given them to trade for food, shelter, and clothing. It was just the beginning of their long walk.

Starting the Long Walk

From Galveston Bay, the three English sailors apparently followed the example of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (c. 1490 to c. 1560), probably without knowing it. The Karankawas would have headed them in the right direction, as they had Cabeza de Vaca decades earlier. Ingram might also have encountered an interior trader to imitate and to use as a guide, but that much good luck was not necessary. More likely they simply took advantage of encouragements they received from other travelers they encountered along the well-used trails. The men would have headed north along the Trinity River, probably leaving the river at what is now Livingston and striking northeast toward Nacogdoches, just as Cabeza de Vaca probably did 40 years earlier. And like him, they found that as strange-looking aliens having gifts but no involvement in regional conflicts, they could travel freely and be welcomed warmly.

Ingram's decision to head north toward what is still known as Nacogdoches had to have been determined not just by trading opportunities but also by the hazards of sticking to a more coastal route. The Atacapas lived eastward of the Karankawas along the coast, an area dominated by vast swamps along the lower Sabine River. The Atacapas were destitute hunter-gatherers like the Chichimecs, with little to trade. There were also fewer good trails in that direction because of extensive swamps. The choice was easy. Ingram and his companions almost certainly traveled north to Nacogdoches. The constraints they faced forced a choice that made Nacogdoches the second highly probable waypoint of the long walk.

It would have taken them about twelve days to walk the 178 miles (286 km) to this trading center at an intersection of the trail from the coast with the bigger San Antonio-Nacogdoches Trail. This bigger trail would later become the Camino Real of Spanish colonial Tejas. In Nacogdoches, they would have found a ready market for what they carried, and they would have exchanged it for things like food, lodging, and new clothing.

Caddoan Culture

Their arrival in Nacogdoches brought them to a new culture. This was the domain of Caddoans, a set of related nations found in adjoining portions of Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana. Here, too, it is likely that some older people probably remembered Cabeza de Vaca. The Caddoans were prosperous farmers living in large permanent towns having earthen platform mounds on which temples and the houses of leading people were built. Their crops included maize, beans, squash, and sunflowers, domesticated foods of the Eastern Woodlands that would become familiar to Ingram in the coming months. So too would the important roles of women in this and other farming societies Ingram would pass through, all the way from east Texas to northern Florida and beyond. Ingram was impressed by the maize: "They have a kind of grain the ear of which is as big as a man's wrist of his arm, the grain is like a flat piece. It makes very good white bread." Ingram must have encountered tortillas and other Mexican foods at San Juan de Ulua, but this was probably his first exposure to the staple crops of North American agriculture that made such foods possible.

The Caddoans had matrilineal social organizations, in which descent was reckoned along female lines. Families organized around senior women were grouped into exogamous clans; young people were required to marry outside their birth clans. However, clans probably served not so much to regulate marriage as to facilitate trade with neighboring nations. Trade transactions were couched as mutual gift exchanges, and clan names allowed fictive kinship to facilitate trade, even between people who did not share a common language. Curiously, Caddo political offices tended to follow male lines, even though that inheritance necessarily crossed clan lines.

De Soto's expedition had reached interior Caddoan towns farther to the northeast in 1541, but there had been no Europeans in Caddoan territory since then. Ingram and his partners were well received, and it should be no surprise to modern readers that the Caddo language was the lingua franca of the region at the time.

Ingram, Browne, and Twide did their best with the unexpected welcome they received from their first Caddoan hosts. As usual, Ingram referred to the leading man of the town of Nacogdoches as a 'king.' His memory of it was that the name of the man's domain was "Giricka". The king had the three men stripped of their clothing so their hairy white skin could be examined by those present. There was general curiosity and discussion about these three strange men, but no evidence of malice. The king allowed them to get dressed, conduct their trading business, and move on without harm or ill will. The three men were as novel to the Caddoans as the Caddoans were to the Englishmen. Nudity was not necessarily inappropriate or shameful here, so examination of their pale skins where the sun did not usually tan them was a harmless curiosity, not a calculated indignity.

Ingram reported that there were many large communities in the region. Major centers were scattered 100 to 200 miles (160–320 km) from each other, and their leaders seemed to be in constant conflict with one another. As peaceful traders, the three men could pass between these major towns and the smaller ones between them without difficulty.

Conclusion

Ingram and his two companions used a vast well-worn network of native American trails, picking up native sign language while getting advice and directions from travelers they encountered. They were accommodated as strange-looking itinerant traders in towns all along the way. When they reached northern Florida, they found out that the hoped-for French outpost had been destroyed by Spanish forces, and they had to plan a new destination. They decided that their only alternative was distant Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. After hiking for a total of eleven months, they were rescued by a French ship on the Bay of Fundy. They had hiked and canoed over 3600 miles (5900 km), through America. David Ingram, Richard Browne, and Richard Twide were welcomed home in London in early 1570. They received instant fame and were rewarded by their astonished former captain. Ingram's experiences would later involve him in further adventures and a role in English efforts to colonize North America.