The Hymn to Nisaba (c. 3rd millennium BCE) is a poem praising Nisaba, the Sumerian goddess of writing and accounts who also served as scribe of the gods. The poem is officially dedicated to Enki, the god of wisdom (sometimes given as her father, sometimes as “patron”), but the majority of the text focuses on Nisaba and her attributes.

Nisaba (also given as Naga, Se-Naga, Nissaba, and Nidaba) was especially popular during the Early Dynastic Period in Mesopotamia (2900-2334 BCE) as, according to scholar Jeremy Black, “without her, harvests could not be calculated, nor bread and beer offerings apportioned” since she was the goddess of accounts who made sure records were accurate (Literature, 292). She was also originally a grain goddess associated with fertility and her power to engender and increase carried over from an agricultural deity who made the crops grow to a literary goddess who inspired written works.

The hymn, which was almost certainly originally sung to musical accompaniment, would have been performed at one of her shrines or sanctuaries, or even at one of the temples dedicated to Enki, but she had no temples of her own. The act of writing seems to have been the primary form of worship for Nisaba and so it is most likely the hymn was sung in one of her sanctuaries which were attached to libraries and scribal houses. Her association with writing, with these places of learning, as well as her connection with the construction of monuments and temples – which obviously required accounting – link her with the Egyptian goddess of writing, Seshat.

Nisaba was the spark of inspiration that allowed a scribe to create any written work.

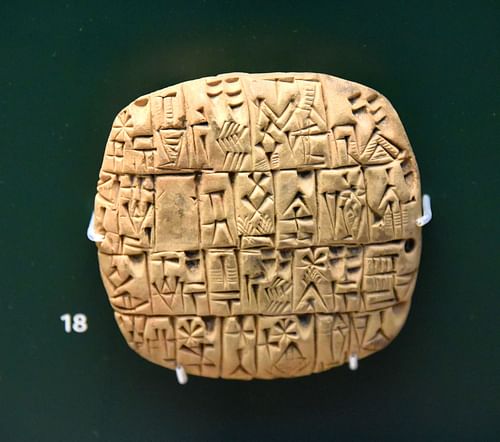

Her status declined during the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE) and, by that time, the Hymn to Nisaba had become primarily a writing exercise students would copy to learn simple Sumerian grammar. She was replaced as the goddess of writing by the Babylonian god Nabu during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE) when male deities superseded females overall. The cuneiform tablet of the hymn was found in the ruins of the sacred temple precinct of the city of Lagash in the mid-19th century when European archaeologists were engaged in concerted efforts at excavating the cities of ancient Mesopotamia.

Nisaba

Writing is thought to have been invented in Sumer to facilitate long-distance trade. Merchants supplying a certain amount of grain, beer, livestock, or any other commodity needed to have some means of communicating clearly and so writing developed to meet this need. Early pictographs eventually gave way to phonograms (symbols representing sounds) c. 3200 BCE in the city of Uruk and Nisaba, associated with grains – a staple commodity – became linked with written records on grain shipments and then with writing itself.

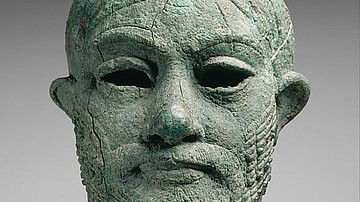

Nisaba was the spark of inspiration that allowed a scribe to create any written work and came to be known as ‘The Lady – in the place where she approaches, there is writing” and a tradition developed of students in scribal schools ending a composition with “Praise be to Nisaba!” (Monaghan, 8-9). An early pictograph represents her as an ear of grain in the Early Dynastic Period before she became goddess of writing and was then represented as a woman holding a tablet of the heavens and a gold stylus. By this time, she was regarded as the daughter of Enlil, king of the gods, and his consort Ninlil. During the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE) she was associated with the city of Ur before becoming the patron goddess of the city of Eresh (also given as Eres) during the Isin-Larsa Period (c. 2025-1763 BCE).

She is sometimes given as the daughter of Enki, however, with Ninlil as her daughter and Enlil as her son-in-law and this is how some scholars interpret her depiction in the hymn. Enki is seen opening up the House of Learning for her, giving her the lapis lazuli tablet and, in some interpretations, this and other details identify Enki as her father while, in others, he is her patron who, as the god of wisdom, would naturally encourage literacy. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek notes:

Mesopotamians recognized Enki as the god who brings civilization to humankind. It is he who gives rulers their intelligence and knowledge; he `opens the doors of understanding’…he is not the ruler of the universe but the gods’ wise counsellor and elder brother…Most importantly, Enki was the custodian of the meh, which the great Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer explained as the `fundamental, unalterable, comprehensive assortment of powers and duties, norms and standards, rules and regulations, relating to civilized life’. (30)

Whether as her father or patron, then, Nisaba – and so writing itself – was associated with wisdom and the essential elements of civilization. The opening lines of the hymn, however, also identify her as the daughter of the sky god Anu and earth goddess Uras (also given as Unas) the original divine couple in Sumerian religion who then passed their position to Enlil and Ninlil. Nisaba was therefore identified with the oldest and most prestigious deities in the Sumerian pantheon.

Hymns in Mesopotamia

As with the works written in praise of these other gods, the Hymn to Nisaba is a devotional piece which names the attributes of the deity while giving thanks for the gifts they give to humanity. Scholar Stephen Bertman comments:

Most of the hymns were probably composed by priests, and they were set down in writing as an act of piety. Once transcribed, the words of praise could then be copied and recited by others. Such songs of praise may have been accompanied by musical instruments…The hymns provide us with the names of the major divinities the Mesopotamians worshiped and tell us where their chief temples were located. The most elaborate hymns are like spiritual kaleidoscopes, radiant with divine epithets and attributes and illuminated with colorful shards of myth. (172)

Hymns could also serve a practical purpose, in addition to praising a deity, as in the case of the Hymn to Ninkasi, Goddess of Beer, which is at once a praise song and a recipe for brewers. The brewers would sing the Hymn to Ninkasi while they brewed and, in this way, not only memorized the recipe but were able to pass it down to the next generation.

Music was highly valued in Mesopotamia in any era and hymns are thought to have been sung to the accompaniment of drums, lyres, reed pipes, and others whose names are known but have not been firmly identified. The Akkadian word for music, nigutu, also means joy and an elevation of the spirit and scholar Samuel Noah Kramer links this with the cadence of the hymns to argue that poems were sung to music at religious services, royal ceremonies, and simply for entertainment purposes. A piece like the Hymn to Nisaba would then have been sung with musical accompaniment to elevate participants in their praise of the goddess.

Summary

The hymn begins with a description of Nisaba holding her lapis lazuli tablet and identifies her as “born of Uras” and also “endowed with fifty great divine powers” which might identify her with the meh of Enki. The E-kur mentioned is Enlil’s temple in the city of Nippur. In line 7, the line “Aruru of the Land” identifies her with the Mother Goddess Ninhursag as does the line “engendered in wisdom by the Great Mountain” as Ninhursag’s name means “Lady of the Mountain” sometimes given as “Lady of the Great Mountain”. She is then further identified with An, the ancient sky god, and Enlil, who assumed his role.

Lines 14-20 reference her role as a grain goddess (“corn” in line 14 should be understood as grain, not maize) and how she has caused abundance at harvest prior to putting on the “holy priestly garment” which would be her present role as goddess of writing. Her former role as grain goddess is referenced in lines 21-26 in Kusu and Ezina, two names for the grain goddess Ashnan (or two aspects of this goddess) who has now assumed Nisaba’s responsibilities as an agricultural deity. This passage also relates how, in order to keep Kusu and Ezina happy, Nisaba will appoint an en-priest (High Priest) to help in managing their affairs, presumably meaning an accountant to assist in recording and dispersing the harvest.

Lines 27-35 detail Enki’s patronage of Nisaba in providing her with the lapis lazuli tablet and opening for her the “house of learning” in the abundant and mythical land of Aratta, the original home of the goddess Inanna before she came to Uruk, further linking Nisaba with Enki since, in some myths, Inanna is Enki’s daughter. The passage goes on to mention the E-zagin (also given as E-zagina), the lapis lazuli house of learning which Enki seems to be opening to her in gratitude for her patronage of the city of Eres (Eresh).

In lines 36-50, Enki is shown in his city of Eridug (Eridu) in the Abzu, the realm of freshwater below the earth, especially associated with Enki and Eridu, which fertilized the land and provided water for drinking and irrigation – and so life – to the people. The Hal-an-kug was the counsel house in which Enki conferred with himself but may also refer to his temple. The entire passage builds toward the end line which, unfortunately, is not complete. It seems, however, that Enki has taken counsel with himself and offers some sort of sacrifice or divine gesture in praise of Nisaba.

Lines 50-55 are simply praises for Nisaba and lines 56-57 are the official dedication of the hymn to Enki who has given Nisaba her powers, insight, and the gifts she then shares with humanity. The last line thanks Enki for his care and patronage of Nisaba because, without him, she would not be able to provide for people as she does but, as the text makes clear, the entire work is a praise of the goddess.

The Text

The following passages are taken from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by Jeremy Black, et. al.

1-6: Lady colored like the stars of heaven, holding a lapis-lazuli tablet! Nisaba, great wild cow born of Uras, wild sheep nourished on good milk among holy alkaline plants, opening the mouth for seven...reeds! Perfectly endowed with fifty great divine powers, my lady, most powerful in E-Kur!

7-13: Dragon emerging in glory at the festival, Aruru of the Land...from the clay, calming...lavishing fine oil on the foreign lands, engendered in wisdom by the Great Mountain! Good woman, chief scribe of An, record-keeper of Enlil, wise sage of the gods!

14-20: In order to make barley and flax grow in the furrows, so that excellent corn can be admired; to provide for the seven great throne-daisies by making flax shoot forth and making barley shoot forth at the harvest, the great festival of Enlil - in her great princely role she has cleansed her body and has put the holy priestly garment on her torso.

21-26: In order to establish bread offerings where none existed, and to pour forth great libations of alcohol, so as to appease the god of grandeur, Enlil, and to appease merciful Kusu and Ezina she will appoint a great en priest and will appoint a festival; she will appoint a great en priest of the Land.

27-35: He (Enki (?)) approaches the maiden Nisaba in prayer. He has organized pure food-offerings; he has opened up Nisaba’s house of learning, and has placed the lapis-lazuli tablet on her knees, for her to consult the holy tablet of the heavenly stars. In Aratta he has placed E-zagin at her disposal. You have built up Eres in abundance, founded from little…bricks, you who are granted the most complex wisdom!

36-50: In the Abzu, the great crown of Eridug, where sanctuaries are apportioned, where elevated…are apportioned – when Enki, the great princely farmer of the awe-inspiring temple, the carpenter of Eridug, the master of purification rites, the lord of the great en priest's precinct, occupies E-Engur, and when he builds up the Abzu of Eridug, when he takes counsel in Hal-an-kug when he splits with an axe the house of boxwood; when the sage's hair is allowed to hang loose, when he opens the house of learning, when he stands in the street of the door of learning; when he finishes (?) the great dining-hall of cedar, when he grasps the date-palm mace, when he strikes (?) the priestly garment with that mace, then he utters seven…to Nisaba, the supreme nursemaid:

50-55: O Nisaba, good woman, fair woman, woman born in the mountains! Nisaba, may you be the butter in the cattle-pen, may you be the cream in the sheepfold, may you be keeper of the seal in the treasury, may you be a good steward in the palace, may you be a heaper up of grain among the grain piles and in the grain stores!"

56-57: Because the Prince [Enki] cherished Nisaba, O Father Enki, it is sweet to praise you!

Conclusion

During the Old Babylonian Period, as noted, Nisaba’s status declined along with all the other female deities when Hammurabi elevated the god Marduk as patron of Babylon and male deities in general above females. Nisaba was replaced by Marduk’s son, Nabu, who became the god of writing, wisdom, learning, prophecy, the patron god of scribes, and the divine energy allowing for agricultural growth and abundant harvests.

The Hymn to Nisaba, which, though a praise song, had served educational purposes earlier in scribal schools, increasingly became solely used as a writing model for grammar. Jeremy Black comments:

The Hymn to Nisaba belongs to a curricular grouping known as the Tetrad, which comprises four hymns in simple Sumerian which were occasionally used as a steppingstone between the elementary curriculum and the Decad. Eight of the first nine lines of the hymn are also attested on a stone tablet from late third-millennium Lagash, while several much older compositions from Suruppag and Abu Salabikh are dedicated to Nisaba as well. (292)

The Tetrad and Decad were groups of training compositions in scribal schools. The Tetrad was comprised of groups of four and the Decad groups of ten and the former were considered introductory texts which prepared a student for the more difficult Decad. Nisaba’s name continued to be known in this context until the fall of Babylon to Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) in 539 BCE.

Afterward, the region was part of the Achaemenid Persian Empire until it fell to Alexander the Great in 330 BCE. How Nisaba was regarded during the time between 539-330 BCE is unclear. It seems she still had followers who revered her as a goddess of writing as late as the Seleucid Period in Mesopotamia (312-63 BCE) but vanishes afterwards. Her name was forgotten until the cuneiform text was deciphered in the 19th century and her story and once popular hymn were brought to light.