During the Renaissance (1400-1600) just about any artist of worth found themselves commissioned at some point in their careers to produce an altarpiece. Some of the greatest names in European art were so called upon, from Jan van Eyck to Titian. Designed to stand behind or actually on the altars within churches, altarpieces could be composed of painted panels, sculptures or both. They were designed to wow the congregation with striking images of the Bible story, and so spectacular were some of these works that they were kept closed or even hidden for most of the year, only to be fully revealed on very special occasions like Easter and Christmas.

Function

Altarpieces were designed to perform several functions and were typically placed either on or at the back of the church altar, the consecrated table priests used to place items used in a particular service. The two types are known as retable (on the altar) and reredos (behind), but there was no formal requirement for them and no standard form. Many churches had secondary altars along the sides of the church or in niches, and these were often given altarpieces, too. The altarpieces for the main altar were the focus of the Mass or service, intended to draw the attention of the congregation to the centre of the ritual activity, especially when the priest had his back to the congregation. Altarpieces could also remind of the dedication of the altar by showing a representation of the relevant saint or a key scene from the Bible, and they promoted prayer and contemplation. Other imagery might remind of who had founded the altar or an important personage buried nearby within the church. As churches often had several altarpieces, they were typically used on a rotation basis, matching their particular artistic subject to the service.

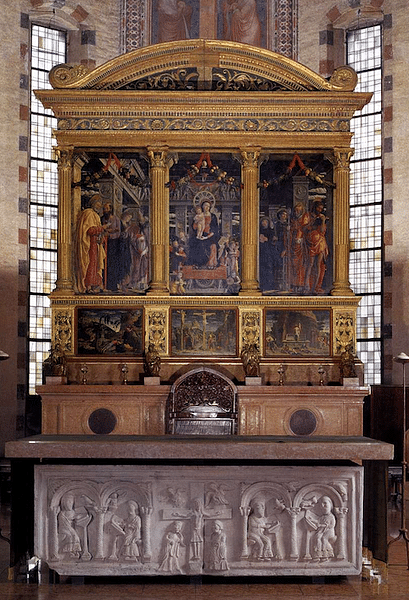

While Italian altarpieces were often monumental facades with architectural elements like columns (see the 1456 San Zeno monastery altarpiece in Verona by Andrea Mantegna, for example), in northern Europe, particularly, folding altarpieces were very popular as they could be closed by folding wings on either side. This arrangement had two functions, the first was that the main images could be dramatically revealed to the audience. The second was that closing the wings offered more protection to fine works of art painted on the interior side. Threats to oil paintings and their expensive bright pigments, especially, came from sunlight, candle smoke, and potentially damp environments. It is interesting to note the relatively high instance of small damages to the exteriors of altarpieces in comparison to their interiors, suggesting that they were most often kept closed. This precaution is further referenced in specific instructions for churches such as this one from Andreas Stoss, the Prior of the Carmelite house in Nuremberg:

The altarpiece is to be opened only on the festivals of the Nativity, Easter, Pentecost, and the two days following, Ascension, Trinity, All Saints, Epiphany, Corpus Christi, the Dedication of the Convent's Church, and all festivals of the Blessed Virgin Mary. On the day of a festival it is to be closed straight after second Vespers. Twice every year it is to be cleaned. And there are not to be large lights on the altar, on account of the smoke two small wall candles are enough and any others should be placed away from the altar.

(Nash, 229)

Prayers were offered to altarpieces by worshippers, an action sometimes seen in other artworks, particularly of rulers eager to show themselves as suitably pious. An excellent example is a parchment illustration dating to c. 1502 showing James IV of Scotland (r. 1488 to 1513) kneeling in prayer to an altarpiece showing the Salvator Mundi. More humble worshippers might visit a church when there was not a service and pray to the altarpiece which might be kept in a side chapel.

Altarpieces and other painted or sculptural works within a church were usually covered during Lent, another advantage for folding versions. Certain churches might also cover their altarpieces and only reveal them on specific feast days or services. Multi-panelled altarpieces might be only partially opened for some services and so were very rarely seen fully opened. Only on a very special occasion like a Christmas or Easter service would all of the church's altarpieces have been placed around the interior, uncovered and all fully opened at once, providing worshippers with a rare visual treat of bright oil pigments and glittering gilding, adding to the festive air of the occasion. Sometimes 'hidden' altarpieces could be viewed privately on the payment of a fee, something Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) did on his tour of churches in the Low Countries in 1521.

Design & Materials

Altarpieces could take several forms and use various materials, although gilded wood or alabaster are the most common during the Renaissance period. Many different types of wood might be used such as limewood, oak, pine, and walnut. Wooden sculptures were coated with a layer of chalk and glue so that the next layer, the paint, did not soak into the wood. Areas meant to be gilded were first painted with bole, a red material that made gold leaf appear more brilliant. Gold leaf was then polished or small areas were painted over and scored to reveal the gold underneath. Painted panels used either tempera or, more commonly in the north of Europe, oil paints.

Diptychs have two painted or sculpted (in high relief or in the round) panels, and triptychs have three hinged panels. The central panel of a triptych is often larger (although not always) and it can be protected by folding the panel on either side in front of it. During the Renaissance, the polyptych form was very popular, that is an altarpiece with many more than three panels, sometimes as many as 20. Sometimes the frames of these panels are very plain, sometimes gilded and very decorative and, on other occasions, even made to resemble architectural elements of the church itself. Altarpieces can combine painting and sculpture, often having the former on the outer and closed panels but sculpture within the central space.

The central panels are usually more richly decorated and show a more complex narrative scene than the outer panels. When closed, many altarpieces present only two panels, and these often have paintings that depict stone sculptures using a limited range of colours, often shades of grey (a technique known as grisaille).

Later altarpieces, particularly in Italy, could be composed solely of free-standing sculpture. These figures were often designed to be moved around during certain services and so had wheels and even jointed limbs. As the Renaissance drew to a close, a single large canvas painting began to replace the function of three-dimensional altarpieces.

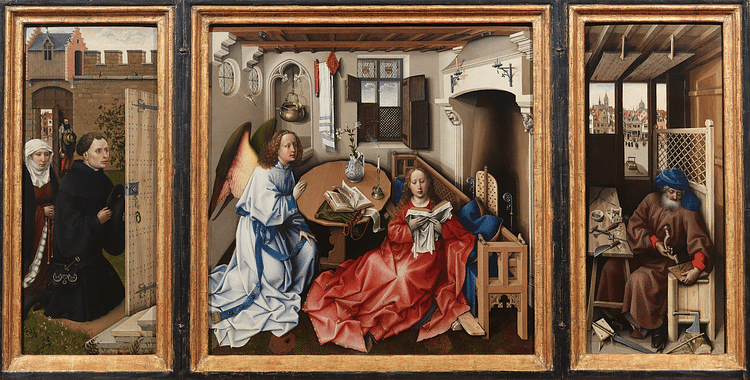

Smaller altarpieces were made for the private chapels of wealthy individuals, and these could be made from precious materials such as ivory. Perhaps the most celebrated example of a smaller altarpiece meant for private use is a c. 1425 triptych, the Mérode altarpiece by Robert Campin. Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, it measures open 118 x 65 cm (46 x 25 inches) and shows the Annunciation using an interesting early attempt at spatial perspective.

Subject Matter

The paintings or relief sculptures in an altarpiece usually depict a specific theme. With several panels, a story could be told using only images such as the key events in the life of a saint. Common themes include the Annunciation, the Nativity of Jesus, the Virgin Mary surrounded by saints, the Last Supper, and the Crucifixion. There could also be more obscure subjects, often complex stories that lend themselves to a visual narrative across many panels. An example of this is Paolo Ucello's (1397-1475) six-panel Profanation of the Host (c. 1468), now in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino. The panels tell the story of a woman who steals a consecrated host in order to repay a loan to a Jewish moneylender. The authorities find out about this sacrilegious act and apprehend both of them. The woman is hanged while the moneylender is burnt at the stake.

Multi-panelled altarpieces gave space not only for the central religious figures but also those who had perhaps commissioned the piece or played a prominent role in the church's foundation. These mere mortals could be represented in the wings at a respectful distance from the sacred figures. Sometimes, even the artists themselves appear as one of the figures in a minor scene.

Finally, although altarpieces as a genre did contain certain restraints in terms of what the commissioner, church, and audience expected, painted panels, in particular, did offer Renaissance artists an opportunity to express their talent and passion for some of the themes that define this period of art. Consequently, we can see in many altarpieces scenes which celebrate the form and proportions of the human body capture dramatic postures, play with perspective, reinvent traditional iconography, and create a strong emotional response from the audience.

Selected Masterpieces

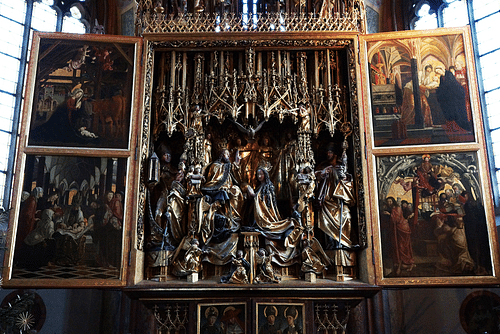

The Saint Wolfgang Altarpiece

The high altarpiece in the church of St. Wolfgang in Salzkammergut, Austria was completed in 1481. Designed by Michael Pacher (1430-1498), it is made of pine and spruce wood, which has been richly painted and gilded. It is an excellent example of an altarpiece where the front painted panels open onto a large collection of central sculptures. Both the paintings and the sculptures are set in impressive architectural scenes. When open, the altarpiece measures 10.88 x 6.60 metres (around 35 x 21 ft). A technique of Pacher's was to use white to pick out the central figures in both his painted and sculptured panels.

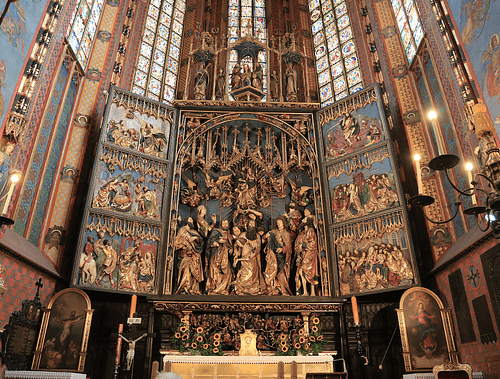

Altarpiece of the Death of the Virgin, Krakow

The 1489 altarpiece by Veit Stoss in Saint Mary's Basilica, Krakow, Poland, is an excellent example of just how monumental the closing panels idea could become. The two massive doors, each showing three large painted panels, can be opened to reveal a richly gilded assembly of figure sculptures. The work is 13 metres high (over 42 ft), and the central figures are 2.7 metres (12 ft) in height. The panels show scenes from the life of Mary and Jesus while the central figure-group shows Mary with the 12 Apostles.

Altarpiece of the Holy Blood, Rothenburg

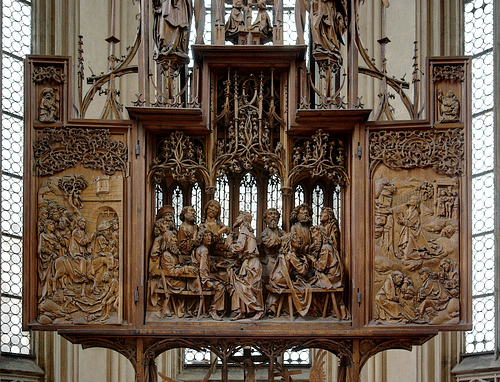

The altarpiece of the Holy Blood in the church of Saint Jacob, Rothenburg, Germany was made by Tilman Riemenschneider (c. 1460-1531). Completed by 1505 and highly ornate, it is made of glazed limewood, with only small touches of colour used for details such as eyes, lips, and blood. It was designed to showcase the chapel which contained a holy relic of Jesus Christ's blood. The central panel shows the Last Supper, the left panel the entry into Jerusalem, and the right panel a scene with Judas. The altarpiece was meant to be admired from both sides since the rear has ornate chapel windows which permitted the figures from the other side to be lit from behind, compensating somewhat for the lack of colour and helping to distinguish the figures when seen from afar.

Bellini's San Zaccaria Altarpiece

Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430-1516) was commissioned for several altarpieces in Venice, but his most celebrated today is in the church of San Zaccaria. Completed c. 1505, it is a curiously pious and tranquil piece which shows the sacra conversazione theme, that is the Virgin and Child surrounded by saints and well-wishers. The altar panels are several metres high and elaborately framed to mimic contemporary developments in architecture. They are much larger works than seen in the altarpieces of northern Europe.

The 5 metres (16 ft 4 in) high central panel has a symmetrical architectural background, which is curiously open at the sides to a landscape of trees. A calming effect comes from the reduced number of figures than was traditional in such scenes and the arrangement and attitude of those figures, all of whom are gazing downwards. There are, too, little tricks of perspective which seem to give the figures more space to exist in. These techniques include the columns behind columns, the checkerboard flooring, and the domed ceiling. Despite the tranquillity of the scene, Bellini has not neglected his love of colour, as seen in the vibrant robes of blue, red, yellow, and green.

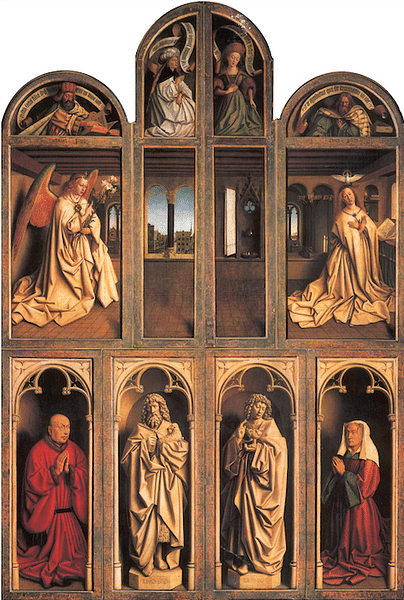

The Ghent Altarpiece

The most famous of all Renaissance altarpieces is The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, more widely known as the Ghent Altarpiece. Its popular name derives from its location, St. Bavo Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium. The work was created in 1432 and is usually credited to Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441). There is, however, an inscription on it which states: "The painter Hubert van Eyck, greater than whom no one was found, began [this work]; and Jan, his brother, second in art [carried] through the task". The authenticity of this inscription, which is actually a 16th-century transcription of the (possible) original, has been questioned by some art historians and linguists. The debate has not yet been resolved as to exactly who painted it or which parts.

The altarpiece is composed of 12 framed panels painted on both sides (oil on oak). When opened, the altarpiece measures 5.2 x 3.75 metres (17 ft x 12 ft 4 in). It was originally meant to stand in what was then the Vijd Chapel in the church of Saint John the Baptist, which has since become St. Bavo Cathedral. The work was commissioned by Jodocus Vijd, and he appears in the bottom left panel when the piece is closed shut; his wife, Elizabeth Borluut, appears in the lower right panel. The other panels on the reverse or exterior side show an Annunciation scene with two prophets, the two saint Johns (masterfully painted to appear as sculptures), two sibyls, the archangel Gabriel, and the Virgin Mary. It is the other side, though, which has the star panels.

The lower interior central panel gives the piece its name and shows a crowd worshipping a lamb, symbol of Jesus Christ and his sacrifice at the crucifixion, The Adoration of the Lamb of God by the Elect. The upper panels show God enthroned between the Virgin and Saint John the Baptist, and various angels. The left wing panels show a naked Adam, singing angels and knights while the opposite wing has Eve, organ players, and hermit and pilgrim saints. The overarching theme seems to be the redemption of humanity.

The figures in the often complex scenes are given a realistic three-dimensional appearance using colouring and shading effects. The figures are given hyperrealistic details such as Adam's evident anxiety in the far left panel. The scenes are all given jewel-like colouring and simulated gold leaf that would have made the scenes shine out from the dim recess of the church's altar.

The altarpiece has been threatened many times, from Calvinist extremists in the 16th century to German troops in the 20th century. Stolen during the Second World War, the altarpiece was rescued from its hiding place in an Austrian salt mine. In the 1940s, it was the first work of Renaissance art to undergo detailed scientific analysis. Today, it is back in the Saint Bavo Cathedral, but not in its original position. The miraculous survival of the Ghent altarpiece and many others like it is, perhaps, above all, a testimony to their artistic value, appreciated not only by worshippers and art lovers but also by Reformists and looters alike.